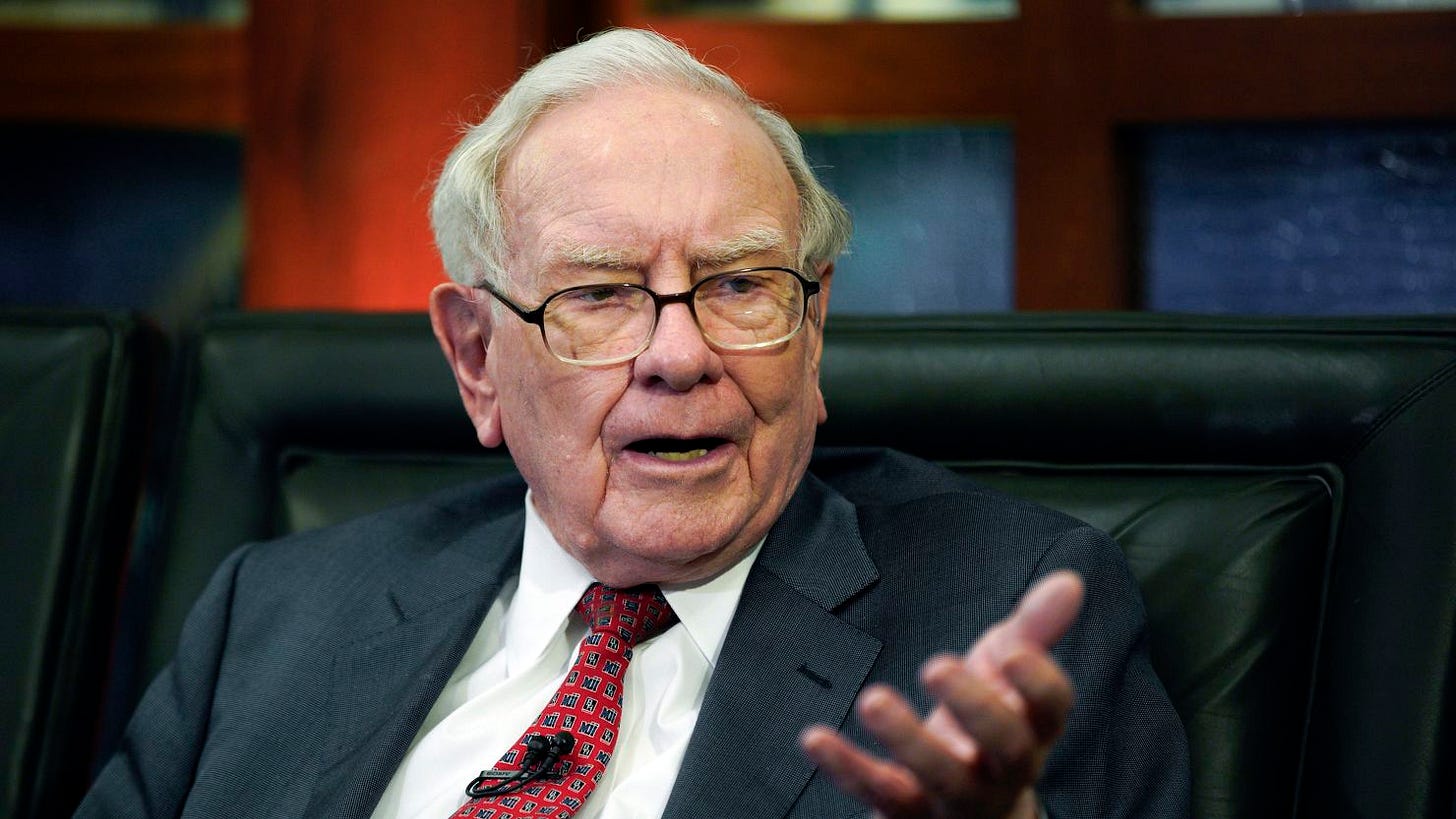

Anthology #4: Warren Buffett

Lessons from Warren Buffett on his mentors, Charlie, portfolio company leaders, business partners, and family

Hi there! Welcome to A Letter a Day. If you want to know more about this newsletter, see "The Archive.” At a high level, you can expect to receive a memo/essay or speech/presentation transcript from an investor, founder, or entrepreneur (IFO) each edition. More here. If you find yourself interested in any of these IFOs and wanting to learn more, shoot me a DM or email and I’m happy to point you to more or similar resources.

If you like this piece, please consider tapping the ❤️ above or subscribing below! It helps me understand which types of letters you like best and helps me choose which ones to share in the future. Thank you!

Anthology #4: Warren Buffett.

If you read this newsletter, you know about my compilations. In fact, you’ve probably even bookmarked a few. But you’ve probably (definitely) never actually read one cover-to-cover.

Unlike my compilations, which range from tens to thousands of pages, or my letters, which are typically a single letter that gives you insight into a single person, Anthologies will be my way of telling a story of some of the people and companies I find interesting through a series of letters, notes, quotes, and/or videos (important: not “the” story, but “a” story).

Anthology

Introduction

KG Note: I will be in Omaha for Berkshire’s Annual Meeting this weekend. If you would like to try and meet up, or are hosting any events I can attend, please email me at kevin@12mv2.com or DM me on Twitter.

Warren Buffett is, perhaps, the most studied investor in history. His every letter, interview, investment, and offhand remark has been parsed for wisdom. Entire cottage industries have formed around tracking and understanding how he thinks, how he invests, and how he leads. (I myself have compiled ~5,000 pages of his words here.)

Yet amidst the ocean of primary documents and secondary analysis, one revealing path remains unstudied—a trail marked not by what Buffett himself has said, but by what he has deliberately chosen to endorse.

This collection follows that trail. While Buffett has recommended hundreds of books, both offhand and officially, he has written the foreword for just 15 of them.

In a world where his words carry immense weight, lending his name is no small gesture. Buffett has long warned, "It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it." He has lived by that principle, guarding his name with even more care than he applies to capital allocation.

So when he chooses to attach his name to a book—not merely with a passing recommendation, but with a thoughtfully penned foreword—it signals something deeper. These are not casual approvals. They are reflections of what Buffett truly values: enduring ideas, principled thinkers, and lessons that transcend market cycles.

While analysts sift through financial statements and shareholders revisit his annual letters and meeting transcripts, this collection offers a different kind of insight. It reveals the books—and by extension, the people and principles—that Buffett deemed worthy of his reputation. In doing so, it grants us a subtler, but no less profound, understanding of the man behind the legend.

As you read these forewords, consider not just the content of each book, but the endorsement that precedes it. In what he chooses to introduce, we find clues to what Warren Buffett cherishes most—integrity, wisdom, and timeless thinking.

This is an invitation to see Buffett not through his own story, but through the stories he has chosen to elevate.

Book Categorizations

Mentors

Intelligent Investor

Life Lessons in Business from Warren E. Buffett & L.A. “Davy” Davidson

Security Analysis

The Ten Commandments for Business Failure

Charlie

Damn Right!

Poor Charlie’s Almanack

Portfolio Company Leaders

From Butler to Buffett

The Pampered Chef

Pleased But Not Satisfied

How to Build a Business Warren Buffett Would Buy

Running with Purpose

Business Partners

Memos from the Chairman

A Plain English Handbook

Family

Giving it All Away

40 Chances

Mentors

Intelligent Investor

By Benjamin Graham and David Dodd (1986 Edition) — Benjamin and David also authored “Security Analysis,” and are seen as the Fathers of Value Investing.

Few books have shaped Buffett’s life like this one. He first read The Intelligent Investor at age 19, and it remains, in his words, “the best book about investing ever written.” Graham’s approach—rational, behavioral, patient—became the bedrock of Buffett’s career.

The book doesn’t promise riches, but it offers something rarer—stability. Buffett urges readers to absorb Graham’s discipline and perspective, especially in times of market mania. His advice is subtle but firm: read this book, and you will avoid the most dangerous traps in investing. Not because you’re clever, but because you’re grounded.

Buffett on Intelligent Investor:

I read the first edition of this book early in 1950, when I was nineteen. I thought then that it was by far the best book about investing ever written. I still think it is.

To invest successfully over a lifetime does not require a stratospheric IQ, unusual business insights, or inside information. What’s needed is a sound intellectual framework for making decisions and the ability to keep emotions from corroding that framework. This book precisely and clearly prescribes the proper framework. You must supply the emotional discipline.

If you follow the behavioral and business principles that Graham advocates—and if you pay special attention to the invaluable advice in Chapters 8 and 20—you will not get a poor result from your investments. (That represents more of an accomplishment than you might think.) Whether you achieve outstanding results will depend on the effort and intellect you apply to your investments, as well as on the amplitudes of stock-market folly that prevail during your investing career. The sillier the market’s behavior, the greater the opportunity for the business-like investor. Follow Graham and you will profit from folly rather than participate in it.

To me, Ben Graham was far more than an author or a teacher. More than any other man except my father, he influenced my life. Shortly after Ben’s death in 1976, I wrote the following short remembrance about him in the Financial Analysts Journal. As you read the book, I believe you’ll perceive some of the qualities I mentioned in this tribute.

BENJAMIN GRAHAM

1894–1976

Several years ago Ben Graham, then almost eighty, expressed to a friend the thought that he hoped every day to do “something foolish, something creative and something generous.”

The inclusion of that first whimsical goal reflected his knack for packaging ideas in a form that avoided any overtones of sermonizing or self-importance. Although his ideas were powerful, their delivery was unfailingly gentle.

Readers of this magazine need no elaboration of his achievements as measured by the standard of creativity. It is rare that the founder of a discipline does not find his work eclipsed in rather short order by successors. But over forty years after publication of the book that brought structure and logic to a disorderly and confused activity, it is difficult to think of possible candidates for even the runner-up position in the field of security analysis. In an area where much looks foolish within weeks or months after publication, Ben’s principles have remained sound—their value often enhanced and better understood in the wake of financial storms that demolished flimsier intellectual structures. His counsel of soundness brought unfailing rewards to his followers—even to those with natural abilities inferior to more gifted practitioners who stumbled while following counsels of brilliance or fashion.

A remarkable aspect of Ben’s dominance of his professional field was that he achieved it without that narrowness of mental activity that concentrates all effort on a single end. It was, rather, the incidental by-product of an intellect whose breadth almost exceeded definition. Certainly I have never met anyone with a mind of similar scope. Virtually total recall, unending fascination with new knowledge, and an ability to recast it in a form applicable to seemingly unrelated problems made exposure to his thinking in any field a delight.

But his third imperative—generosity—was where he succeeded beyond all others. I knew Ben as my teacher, my employer, and my friend. In each relationship—just as with all his students, employees, and friends—there was an absolutely open-ended, no-scores-kept generosity of ideas, time, and spirit. If clarity of thinking was required, there was no better place to go. And if encouragement or counsel was needed, Ben was there.

Walter Lippmann spoke of men who plant trees that other men will sit under. Ben Graham was such a man.

Reprinted from the Financial Analysts Journal, November/December 1976.

Life Lessons in Business from Warren E. Buffett & L.A. “Davy” Davidson

By Gwyn Larsen (2007) — Gwyn Larsen is Lorimer “Davy” Davidson’s grandson. Davy was the President of GEICO.

In this foreword, Buffett reflects on a pivotal mentor: Lorimer “Davy” Davidson, the man who introduced him to GEICO and, indirectly, to the insurance business. At age 20, Buffett spent a Saturday with Davidson that changed the trajectory of his life. The value of that meeting, he writes, exceeded his entire college education.

Buffett isn’t just recounting a personal anecdote—he’s celebrating the power of generosity in teaching. Davidson expected nothing in return for his time and wisdom. Buffett frames that kind of mentorship as rare and essential, and holds it up as a model for how business—and life—should be practiced.

Buffett on Davy:

I can think of 100 wonderful adjectives to describe Lorimer Davidson. But if I used every one of them I would not be doing him justice.

Obviously, he was a wonderful businessman and, as you know, a wonderful grandfather. To me, however, he was a friend and teacher, almost without peer. How many other business people would have taken precious time on a Saturday to spend four hours with a 20-year-old who in no conceivable way could be expected to recriprocate the kindness and wisdom that was to be imparted to him.

From that day in early 1951, my life developed far differently than if I hadn’t met Davy. What I learned in those four hours was more valuable than the knowledge that I had acquired in all of my college years. Indeed, Berkshire and I would not even be in the insurance business now if it hadn’t been for Davy’s initial instruction and encouragement. Within months after our meeting, I launched my career in Omaha as a securities salesman by telling people about GEICO. My reputation was established by this recommendation. Imagine the difference in my life if I had initially been encouraging investment in the stock of some public utility or mutual fund.

For the rest of his life, Davy continued to be my teacher and friend. Finally in 1995 I talked to him about my hope to buy the rest of GEICO for Berkshire Hathaway. If I went ahead he would incur a large capital gains tax which otherwise would be avoided by his estate. Almost anyone else would have advised delay. But Davy’s reaction was immediate: “It will be good for GEICO and for Berkshire Hathaway – I’m all for it.”

Gwyn, your grandfather was a very rare man and one all of us should emulate.

Security Analysis (2008)

By Benjamin Graham and David Dodd (Sixth Edition; 2008) — Benjamin and David also authored “Intelligent Investor,” and are seen as the Fathers of Value Investing.

This book, more than any other, laid the intellectual foundation for Buffett’s investment career. In his foreword to the 6th edition, he doesn’t just honor Graham and Dodd’s insights—he pays tribute to the personal influence they had on him as teachers and mentors. Buffett’s reverence for the 1940 edition is palpable: he’s read it multiple times and still considers it essential.

But beyond the ideas, Buffett emphasizes the values these men embodied: generosity, humility, and openness. They taught him not just how to invest, but also how to live. For Buffett, Security Analysis isn’t just a textbook; it’s the bedrock of his origin story.

Buffett on Security Analysis:

There are four books in my overflowing library that I particularly treasure, each of them written more than 50 years ago. All, though, would still be of enormous value to me if I were to read them today for the first time; their wisdom endures though their pages fade.

Two of those books are first editions of The Wealth of Nations (1776), by Adam Smith, and The Intelligent Investor (1949), by Benjamin Graham. A third is an original copy of the book you hold in your hands, Graham and Dodd’s Security Analysis. I studied from Security Analysis while I was at Columbia University in 1950 and 1951, when I had the extraordinary good luck to have Ben Graham and Dave Dodd as teachers. Together, the book and the men changed my life.

On the utilitarian side, what I learned then became the bedrock upon which all of my investment and business decisions have been built. Prior to meeting Ben and Dave, I had long been fascinated by the stock market. Before I bought my first stock at age 11—it took me until then to accumulate the $115 required for the purchase—I had read every book in the Omaha Public Library having to do with the stock market. I found many of them fascinating and all interesting. But none were really useful.

My intellectual odyssey ended, however, when I met Ben and Dave, first through their writings and then in person. They laid out a roadmap for investing that I have now been following for 57 years. There’s been no reason to look for another.

Beyond the ideas Ben and Dave gave me, they showered me with friendship, encouragement, and trust. They cared not a whit for reciprocation—toward a young student, they simply wanted to extend a one-way street of helpfulness. In the end, that’s probably what I admire most about the two men. It was ordained at birth that they would be brilliant; they elected to be generous and kind.

Misanthropes would have been puzzled by their behavior. Ben and Dave instructed literally thousands of potential competitors, young fellows like me who would buy bargain stocks or engage in arbitrage transactions, directly competing with the Graham-Newman Corporation, which was Ben’s investment company. Moreover, Ben and Dave would use current investing examples in the classroom and in their writings, in effect doing our work for us. The way they behaved made as deep an impression on me—and many of my classmates—as did their ideas. We were being taught not only how to invest wisely; we were also being taught how to live wisely.

The copy of Security Analysis that I keep in my library and that I used at Columbia is the 1940 edition. I’ve read it, I’m sure, at least four times, and obviously it is special.

But let’s get to the fourth book I mentioned, which is even more precious. In 2000, Barbara Dodd Anderson, Dave’s only child, gave me her father’s copy of the 1934 edition of Security Analysis, inscribed with hundreds of marginal notes. These were inked in by Dave as he prepared for publication of the 1940 revised edition. No gift has meant more to me.

The Ten Commandments for Business Failure

By Donald Keough (2011) — Donald was the President, COO, and a Director of The Coca-Cola Company. He also served as Chairman of Allen & Co. and Columbia Pictures.

In Don Keough, Buffett sees not only a business leader, but a model of decency and directness. Buffett describes Keough as the embodiment of Coca-Cola itself: consistent, refreshing, and built to last. More than anything, he values Keough’s ability to cut through noise and do the right thing—without ego, but with clarity.

Buffett notes that Keough could have been President if he wanted to be. Instead, he focused on building teams and helping others grow. This foreword is as much a tribute to timeless leadership as it is to friendship.

Buffett on Don:

It has been an article of faith for me that I should always try to hang out with people who are better than I. There is no question that by doing so you move yourself up. It worked for me in marriage and it’s worked for me with Don Keough.

When I’m with Don Keough, I can feel myself on the up escalator. He has an optimistic view of me and what I am to the extent that he raises my sights and makes me believe more in myself and the world around me. When you are around Don, you are learning something all the time. He’s an incredible business leader. The greatest achievement of good executives is to get things done through other people, not themselves. Now here is a guy who is capable of getting all kinds of people from all over the world, men and women who want to help him succeed. I’ve seen him do it.

Maybe it is because no one understands the human aspects of situations better than me. He can advise my kids perhaps better than I can and they love him for that. He does the same for everyone he calls a friend—and that is a lot of people.

The Graham Group, named after my mentor Ben Graham, is a bunch of people who meet every two years or so. All my close friends, including Don, attend. Everyone wants Don to be the keynote speaker. Bill Gates, in particular, always wants it to be Don Keough. He just loves listening to him because Don talks such sense and offers such inspiration. Don can tell you to go to hell so wonderfully you’ll enjoy the journey.

He is on my board at Berkshire Hathaway because he is one of the very few guys I feel I can hand the keys over to.

We go back almost fifty years together, to the time we lived opposite each other on Farnam Street here in Omaha. We were just two guys make a living for our families back then. If we had told you that one of us would become president of The Coca-Cola Company and the other would become head of Berkshire Hathaway, I’m sure you would have said I hope their parents have enough money to support these two.

At one point I knocked on his door and asked him to invest ten thousand dollars or so with me. He turned me down flat. I’d probably have turned me down too back then.

Our families were great friends; the kids were always in and out of each other’s houses. It was very tough on my kids when they had to move to Houston. There were a lot of tears that day when they moved away.

It’s interesting when you think of it. Don and I were living less than a hundred yards away from where my future partner, Charlie Munger, had grown up. Don went to Houston and Atlanta; Charlie landed in Los Angeles. But we later reunited as close friends and business associates, all with a lot of Omaha still in us. Nowadays, of course, a lot of people say they are from Omaha for status reasons!

After Don left Omaha we kept in touch over the years. I’d meet him at the Alfalfa Club or once we even met at the White House. Then he read an article in 1984 in which I praised Pepsi, “preferably with a touch of cherry syrup in it.” The next day he sent me their new product, Cherry Coke, and invited me to taste test “the nectar of the Gods.” After I drank it I told him, “Forget about your testing. I don’t know much about that stuff but I do know this is a winner.”

I switched brands right away and immediately declared Cherry Coke the official soft drink of Berkshire Hathaway.

A few years later I started buying Coke stock but I didn’t tell Don because I felt he might have to tell the company lawyer, and who knows where that would have led. I didn’t want to put him in an awkward position. Anyway, he later called and said, “You wouldn’t happen to be buying a share or two of Coke stock, now would you?” I told him, “It just so happens that I am.” At the time we picked up 7.7 percent of the company.

It was a straightforward decision, especially knowing that he was the president. I saw Coke in 1988 as a company that understood what it was doing and was doing the right thing and was obviously enormously valuable as a result.

If you wanted to invent a human personification of The Coca-Cola Company, it would be Don Keough. He was and is Mr. Coke. He’s of the Ben Franklin school, “Keep thy shop and it will keep thee.” Basically, what he has always done is do the right thing by Coca-Cola and he believes that it will always do the right thing by him.

Don’s best ability is to cut to the chase on an issue, to cut through the bureaucratic fog. Keep it simple is his principle and mine too.

Herbert Allen says that the only two businessmen he knew who could have become president if they had run for office were Jack Welch and Keough. I agree with that; they both had that natural brilliance. They are both people we can learn so much from.

After all these years, every time I see Don Keough, I feel as refreshed as I do after drinking a Cherry Coke. He never loses his carbonation. I’ve seen him on the board of Coke and now at Berkshire. Don is as enthusiastic and committed as ever, full of plans, energy, ideas, daring us all to dream. I am delighted that this book will help so many other people share in that unique Keough vision.

Partner

Damn Right!: Behind the Scenes with Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger

By Janet Lowe (2000) — Janet was an American journalist. She wrote a number of business books, including this biography of Charlie Munger.

Buffett’s admiration for Charlie Munger is legendary. In this foreword, he sets aside numbers entirely to focus on Munger’s moral clarity and personal code. He highlights Munger’s deep integrity, his resistance to ego, and his habit of judging himself by an “inner scorecard.”

This isn’t just a tribute to a friend—it’s Buffett offering readers a quiet roadmap for how to live well and think independently. He makes it clear that what matters most to him is not brilliance, but how brilliance is used. Munger’s greatness, in Buffett’s eyes, lies not in his intellect alone but in his lifelong devotion to rationality, fairness, and quiet generosity.

Buffett on Charlie:

Late in the summer of 1991, I appeared before a house subcommittee chaired by Congressman Ed Markey to answer questions about the Salomon scandal. The hearing room was piled high with TV and print reporters, and I was more than a little nervous when Chairman Markey led off with his first question. He wanted to know whether the reprehensible behavior that had occurred at Salomon was characteristic of Wall Street or rather, as he put it, "sui generis."

Normally I would have panicked at the introduction of such a strange-sounding term: In high school, I barely made it through elementary Spanish and never came close to Latin. But, I had no trouble with sui generis. After all, I knew a walking, talking example: Charlie Munger, my long-time friend and partner.

Charlie truly is one of a kind. I recognized that in 1959, when I first met him, and I have been discovering unique qualities in him ever since. Anyone who has had even the briefest contact with Charlie would tell you the same. But usually they would be thinking of his, shall we say, behavioral style. Miss Manners clearly would need to do a lot of work on Charlie before she could grant him a diploma.

To me, however, what makes Charlie special is his character. It's true that his mind is breathtaking: He's as bright as any person I've ever met and, at 76, still has a memory I would kill for. He was born, though, with these abilities. It's how he has elected to use them that makes me regard him so highly.

In 41 years, I have never seen Charlie try to take advantage of anyone, nor have I seen him claim the least bit of credit for anything that he didn't do. In fact, I've witnessed exactly the opposite: He has knowingly let me and others have the better end of a deal, and he has also always shouldered more than his share of the blame when things go wrong and accepted less than his share of credit when the reverse has been true. He is generous in the deepest sense and never lets ego interfere with rationality. Unlike most individuals, who hunger for the world's approval, Charlie judges himself entirely by an inner scorecard-and he is a tough grader.

On business matters, Charlie and I agree a very high percentage of the time. On social issues, however, we sometimes see things differently. But despite the fact that we both cherish our strong opinions, we have never in our entire friendship had an argument nor found disagreement a reason to be disagreeable. It's very difficult to imagine Charlie on a corner in a Salvation Army uniform-no, make that impossible to imagine-but he seems to have embraced the charity's creed of "hate the sin but not the sinner."

And, speaking of sin, Charlie even brings rationality to that subject. He concludes, of course, that sins such as lust, gluttony, and sloth are to be avoided. Nevertheless, he understands transgressions in these areas, since they often produce instant, albeit fleeting, pleasure. Envy, however, strikes him as the silliest of the Seven Deadly Sins, since it produces nothing pleasant at all. To the contrary, it simply makes the practitioner feel miserable.

I've had an enormous amount of fun in my business life-and far more than if I had not partnered up with Charlie. With his "Mungerisms" he has been highly entertaining, and he has also shaped my thinking in a major way. Though many would label Charlie a businessman or philanthropist, I would opt for teacher. And Berkshire clearly is a much more valuable and admirable company because of what he has taught us.

No discussion of Charlie would be complete without a mention of the beneficial, indeed transforming effect of his wife, Nancy. As a front-row observer of both people, I can assure you that Charlie would have achieved far less had he not had Nancy's help. She may not have entirely succeeded as a Miss Manners instructor-though she tried, oh how she tried-but she has nourished Charlie in a manner that has in turn enabled him to nourish the causes and institutions in which he believes. Nancy is truly extraordinary. What Charlie has contributed to the world-and his contributions have been huge-should be credited not only to him but to her as well.

Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger

By Peter Kaufman (2005) — Peter Kaufman is the Chairman and CEO of Glenair. He also served on the Boards of the Daily Journal and Wesco Financial.

This foreword reads like Buffett’s personal theory of partnership. Disguised as a reflection on Charlie Munger, it’s also an essay on what to look for in a long-term collaborator: intellect, humility, generosity, loyalty, and humor. Buffett writes with warmth and gratitude, but also with precision.

This is not nostalgia—it’s instruction. Munger isn’t just Buffett’s partner; he’s the living embodiment of the business values Buffett holds most dear. In these few paragraphs, Buffett offers the blueprint not just for choosing a partner—but for being one.

Buffett on Charlie:

From 1733 to 1758, Ben Franklin dispensed useful and timeless advice through Poor Richard’s Almanack. Among the virtues extolled were thrift, duty, hard work, and simplicity.

Subsequently, two centuries went by during which Ben's thoughts on these as the last word. Then Charlie Munger stepped forth.

Initially a mere disciple of Ben's, Charlie was soon breaking new ground. What Ben recommended, Charlie demanded. If Ben suggested saving pennies, Charlie raised the stakes. If Ben said be prompt, Charlie said be early. Life under Ben’s rules began to look positively cushy compared with the rigor demanded by Charlie Munger.

Moreover, Charlie consistently practiced what he preached (and, oh, how he preached). Ben, in his will, created two small philanthropic funds that were designed to teach the magic of compound interest. Early on, Charlie decided that this was a subject far too important to be taught through some posthumous project. Instead, he opted to become a living lesson in compounding, eschewing frivolous (defined as "any") expenditures that might sap the power of his example. Consequently, the members of Charlie's family learned the joys of extended bus trips while their wealthy friends, imprisoned in private jets, missed these enriching experiences.

In certain areas, however, Charlie has not sought to improve on Ben's thinking. For example, Ben's "Advice on the Choice of a Mistress" essay has left Charlie in the "I have nothing to add" mode that is his trademark at Berkshire annual meetings.

There was only one partner who fit my bill of particulars in every way—Charlie.

"A partner who is not subservient, who is himself extremely logical, is one of the best mechanisms you can have."

As for myself, I'd like to offer some "Advice on the Choice of a Partner." Pay attention.

Look first for someone both smarter and wiser than you are. After locating him (or her), ask him not to flaunt his superiority so that you may enjoy acclaim for the many accomplishments that sprang from his thoughts and advice. Seek a partner who will never second-guess you nor sulk when you make expensive mistakes. Look also for a generous soul who will put up his own money and work for peanuts. Finally, join with someone who will constantly add to the fun as you travel a long road together.

All of the above is splendid advice. (['ve never scored less than an A in self-graded exams.) In fact, it's so splendid that I set out in 1959 to follow it slavishly. And there was only one partner who fit my bill of particulars in every way—Charlie.

In Ben's famous essay, he says that only an older mistress makes sense, and he goes on to give eight very good reasons as to why this is so. His clincher: "...and, lastly, they are so grateful."

Charlie and I have now been partners for forty-five years. I'm not sure whether he had seven other reasons for selecting me. But I definitely meet Ben's eighth criterion. I couldn't be more grateful.

Portfolio Company Leaders

From Butler to Buffett: The Story Behind The Buffalo News

By Murray Light (2004) — Murray started his career as a reporter and worked his way up to Editor, Managing Editor, VP, and Senior VP of The Buffalo News over 50 years.

When Buffett writes about business, he often returns to one quiet but critical quality: courage. In this foreword, he recalls a pivotal moment when the survival of the Buffalo Evening News hinged on one man’s editorial leadership. During a legal and competitive storm, it was Murray Light’s steady hand and refusal to give in that preserved the integrity of the paper—and, by extension, its future.

This isn’t just a story of an editor; it’s a story of resilience in the face of pressure. Buffett honors Light not for delivering profits but for defending principle. The long-term payoff, he reminds us, isn’t always immediate—but it is enduring.

Buffett on Murray:

I’ll never forget 1977.

Early that year Blue Chip Stamps (later to be merged into Berkshire Hathaway) purchased the Buffalo Evening News. The News had more than double the daily circulation of the Courier-Express, its morning rival, but it had forsaken Sunday publication. The Courier-Express reigned supreme and uncontested on that day, which, then as now, was by far the favorite for advertisers.

There was a mortal threat to the News: throughout the country, one major daily after another had failed when competing with rivals who initially had trailed badly on weekdays but were dominant on Sunday. There were no exceptions to this rule.

My partner, Charlie Munger, and I therefore knew we had to launch a Sunday edition, no matter what the cost. And we promptly did so.

The Courier-Express responded with a lawsuit and found a friendly judge, Charles L. Brieant. He quickly laid down harsh terms for publication that cripped the introduction of our Sunday edition. His actions also devastated the morale of our 1,100 employees. Many had not been happy with our decision to enter the Sunday field—their routine had been uncomplicated before Charlie and I had come to Buffalo—and now they found their beloved paper under attack from all sides. Understandably, most were beginning to rue the day that the News had been sold.

Murray Light was the exception. And he was the one we needed—a brilliant and tireless editor who had to infuse life into a Sunday product that was maimed at birth by the court and sent out to compete with a product that over fifty-seven years had become a deeply entrenched habit for Buffalo citizens.

Murray’s instructions were to put out a first-class Sunday edition, no matter how scarce the ads and how dispirited his troops. Our survival depended on his ability to do so. And Murray pulled it off. The outstanding product he delivered established a solid base of subscribers.

Then after fifteen months, the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled unanimously that Judge Brieant’s decision had been “infected with legal and factual error” and reversed his order. Circulation subsequently began to climb slowly and eventually the better product carried the day.

The News recently recorded its 125th anniversary. It’s a birthday we wouldn’t be celebrating if Murray Light had not been our editor in 1977.

The Pampered Chef: The Story of One of America’s Most Beloved Companies

By Doris Christopher (2005) — Doris was the Founder and CEO of The Pampered Chef.

Buffett has long admired entrepreneurs who build something meaningful from humble beginnings. In this foreword, he tells the story of Doris Christopher and how she turned a $3,000 life insurance loan into a beloved home business. He was drawn not only to the business’s fundamentals—strong cash flow, clear value proposition, no debt—but to Christopher’s character and motivation.

What impressed Buffett most was her desire to protect her company’s future, not cash out. Her “keep it simple” philosophy and user-focused design resonated with his own investing ethos. To Buffett, The Pampered Chef wasn’t just a great business—it was a blueprint for durable, purpose-driven growth.

Buffett on Doris:

In September of 2002, Doris Christopher, the founder of The Pampered Chef, came to see me in Omaha about selling the company. Right on the spot, I knew I wanted The Pampered Chef in the Berkshire Hathaway family. So we immediately made a deal.

The typical “entrance” strategy for acquisitions at Berkshire is to buy a company with great economic characteristics: no debt, a robust balance sheet, and positive cash flow. The Pampered Chef has all of that in spades. But it was Doris herself that cinched the deal for me. I liked her management style—hands-on, straightforward, nurturing, and accessible.

I also liked her reason for selling the company. There was no financial crisis, Doris had no health problems. She and her husband, Jay, simply wanted to plan for the future of their company to make sure it—and The Pampered Chef’s Co-workers and Consultants—would continue to thrive long after Doris retired. That’s the right way for an owner to behave, and therefore our “entrance” strategy made perfect sense to me. And that’s important, because here at Berkshire, we have no “exit” strategy. We buy great businesses to keep. My job is to stay out of the way. And let Doris and her team run the business.

As you will read in this remarkable book, The Pampered Chef was founded in 1980 when Doris Christopher was a thirty-five-year-old suburban former home economics teacher with a husband and two little girls. Her initial goal was limited: she simply wanted to supplement her family’s modest income. She had absolutely no business background. She turned to thinking about what she knew best—food preparation. Why not, she wondered, make a business out of marketing quality kitchenware, focusing on the items she herself had found most useful?

To launch her company, Doris borrowed $3,000 against a family life insurance policy—all the money ever injected into the company—and went to the Merchandise Mart in Chicago to buy the products she would offer for sale. She set up operations in her basement. Her plan was to conduct in-home presentations to small groups of women, gathered at the homes of their friends. While driving to her first presentation, Doris almost talked herself into returning home, convinced she was doomed to fail. But the women to whom she demonstrated her wares that evening loved her, and The Pampered Chef was under way. Working with her husband, Jay, Doris did $50,000 of business in the first year.

Today—the twenty-fifth anniversary of the company—The Pampered Chef has thousands of Kitchen Consultants, serving 12 million customers at one million Kitchen Shows a year.

I saw this business for myself when I attended my first Kitchen Show. I put on my Pampered Chef apron and chopped, tasted, and tested right along with the other guests. I wasn’t a star, however, coming in last in the apple-peeling contest. It was easy to see why the business is a success. The company’s products, in large part proprietary, are well designed, finely crafted, and, above all, useful, and the Pampered Chef Consultants are knowledgeable and enthusiastic.

The Pampered Chef is truly loved by its customers because it has found a need and filled it exceptionally well, helping everyday home cooks to become masters of their own home kitchens and making mealtime preparation quick, easy, and fun. It also offers its Consultants an incomparable business opportunity, allowing men and women to build a home-based business of their own, based on Doris Christopher’s personal blueprint for success. When you read the profiles of The Pampered Chef’s Kitchen Consultants in Chapter 8, you may wonder what you’re doing in your nine-to-5 cubicle while these folks are happily cooking their way to fame and fortune.

At Berkshire Hathaway, we like companies that are easy to understand. Doris Christopher’s “keep it simple” approach has a lot to teach anyone who is reaching for the American Dream. Frankly, if I can’t understand a company’s business, I figure their customers must have a pretty hard time figuring it out, too.

I would challenge anyone on Wall Street to take $3,000 and do what Doris Christopher has done: build a business from scratch into a world-class organization. But follow the simple steps in this book, and it just might happen. Come see me in Omaha when you’ve put together your own recipe for success; we pay cash and Berkshire’s check will clear. In the meantime, read this book. Then, read it again.

Pleased But Not Satisfied

By David Sokol (2007) — David was the Chairman, President, and CEO of NetJets, as well as Chairman of MidAmerican Energy Holdings.

Buffett’s admiration for Dave Sokol came from firsthand observation. For eight years, Buffett watched Sokol lead MidAmerican Energy with consistent success across operations and acquisitions. In this foreword, he emphasizes the rare blend of operational excellence and humility that Sokol brought to the job—qualities Buffett regards as essential but scarce.

The book’s title captures a key value Buffett shares with Sokol: never rest on your last win. Instead, treat each success as a stepping stone. Buffett subtly ties this ethos back to one of his great influences, Walter Scott, who believed in striving continuously, even when ahead.

Buffett on Pleased But Not Satisfied:

Before reading a how-to book on any subject, it’s important to examine the credentials of the author. What Ted Williams writes in The Science of Hitting should be taken seriously by would-be sluggers. If I were to pen a book on that subject, it would make no sense for anyone to go beyond the first page. With an occasion exception – after all, you don’t have to be dead to write a praiseworthy obituary – some successful accomplishments in the field should precede teaching.

Dave Sokol scores at the top in this respect. He brings the equivalent of Ted Williams’ .406 batting average to the field of business management.

I know this because I’ve had a front-row seat for eight years, watching him manage MidAmerican Energy. There he has negotiated and executed a variety of successful acquisitions and led many operating companies to outstanding financial performances. In the process, these companies have delighted their customers and met – indeed, often exceeded – the expectations of their regulators. All this was done by consistent application of the business principles he sets forth in this book.

I believe deeply in the business attitude he learned from Walter Scott – after each success, be “pleased, but not satisfied.” But I have a small confession to make: by the standards of personal behavior and his value to Berkshire Hathaway, I am more than pleased and fully satisfied by all the experiences I have had with Dave.

How to Build a Business Warren Buffett Would Buy: The R.C. Willey Story

By Jeff Benedict (2009) — Jeff is an American author. He has written a number of business books, including this biography of Bill Child and R.C. Willey.

Buffett admires quiet builders—those who create strong businesses not by chasing trends, but by sticking to fundamental principles. In this foreword, he introduces Bill Child, a man who turned a modest furniture operation into a thriving regional powerhouse. Bill didn’t innovate through invention, but by living one principle with radical consistency: treat others as you’d want to be treated.

Buffett uses Bill’s story to highlight the power of reputation and trust in business. He points out that Bill grew his company not by exploiting others, but by serving them—employees, customers, and partners alike. This is the kind of character Buffett looks for in both people and companies.

Buffett on Bill:

Bill Child represents the best of America. In matters of family, philanthropy, business, or just plain citizenship, anyone who follows in his footsteps is heading true north.

I became Bill’s partner in 1995 when Berkshire purchased R.C. Willey. Bill had built that business from sales of $250,000 to a level of $257 million in the year of our purchase. There is nothing easy about the home furnishings business. Bill originally dealt with competitors far larger in sales volume, far better known with consumers, and far better capitalized. But by doing the right things for his customers and associates, he eventually left all of these once-stronger competitors in the dust.

He didn’t do this by inventing something new. He just applied the oldest and soundest principle ever set forth: Treat the other fellow as you would like to be treated yourself. By consistently following this principle he transformed a hole-in-the-wall operation in the tiny town of syracuse into a business that enjoys the trust of millions of his fellow citizens in Utah.

All along the way, Bill has shared his success with others. Berkshire bought R.C. Willey with its Class A shares, and I’ve watched Bill quietly dispense those shares in ways to help people less fortunate than he. He lives the principles to which some others apply only lip service.

Just as I have benefited enormously from knowing Bill personally, you can benefit by getting to know him vicariously through this book. Take the lessons from his life and apply them to your own. You will lead a happier, more productive life as a result.

Running with Purpose: How Brooks Outpaced Goliath Competitors to Lead the Pack

By Jim Weber (2022) — Jim was the CEO of Brooks.

Buffett is famously hands-off with Berkshire Hathaway subsidiaries—except when he sees someone exceptional. In this rare case, he pulled Jim Weber and Brooks Running out from under Fruit of the Loom and made them a stand-alone company. That decision, Buffett writes, was unprecedented. But Weber made it look obvious in hindsight.

Buffett respects Weber’s energy, integrity, and relentless commitment to product quality and company culture. The foreword is both endorsement and instruction: find leaders who love what they do, and then get out of their way. Weber, Buffett makes clear, is one of the rare few who didn’t just earn autonomy—he multiplied it.

Buffett on Jim:

Jim Weber’s career as a Berkshire Hathaway manager is unique.

Throughout my fifty-six-year tenure at Berkshire, the company has followed a dramatic hands-off style in its operations. Today, only twenty-five employees work for the parent company in headquarters, while three hundred sixty thousand go about their jobs in the many dozens of individually managed subsidiary businesses that Berkshire has purchased over the years. Our decentralization is extreme.

Among those many purchases was Fruit of the Loom, a Kentucky-based manufacturer of apparel, best known for men’s underwear. Fruit is successful and well managed, employing about twenty-nine thousand people.

In 2012, Fruit owned several noncore operations, including Brooks Running Company, managed by Jim Weber. Brooks and, more particularly, Jim caught my eye. Jim would catch anyone’s eye; he is a force.

I decided that Jim was simply too talented to not be running his own show, one that would report directly to Berkshire. My course was obvious: Fruit should transfer Brooks to Berkshire, and then Brooks should operate as a stand-alone business.

This decision—the only one of its kind ever made at Berkshire—has been a home run. Despite entrenched and able competitors, Jim has propelled Brooks forward to an extent far beyond my high expectations.

Jim loves running, loves runners, loves his associates, and loves his retailers. Daily he demonstrates that affection in his decision-making. He instinctively understands product design and branding. He will never settle for less than the best for all constituencies and constantly challenges himself.

His enthusiasm for running has been contagious with Berkshire shareholders. During our annual meeting weekend, thousands of attendees turn out for a Sunday-morning 5K. Prior to the event’s pandemic-induced suspension, the crowd grew annually. I expect a new attendance record when an in-person meeting is resumed.

Jim’s passionate story will inspire you just as it inspired me in 2012 to recognize that he would make Brooks a stand-alone star at Berkshire. I will recommend that all Berkshire managers, current and future, read this book.

Business Partners

Memos from the Chairman

By Alan “Ace” Greenberg (1996) — Ace was the CEO and Chairman Bear Stearns.

In the world of business writing, few figures blend wit and wisdom as effectively as Ace Greenberg. Buffett delights in this rare combination, and in this foreword, he praises Greenberg’s ability to translate real managerial insight through humor. He draws a direct line to Where Are the Customers’ Yachts?, one of the great satirical investment texts, suggesting that Greenberg’s writing belongs in the same league.

Behind the jokes is a blueprint for practical business thinking—tight, sensible, and timeless. Buffett doesn’t just admire the humor—he respects the clarity and judgment that underlie it. This is what he values most in communication: candor wrapped in accessibility, insight that doesn’t try too hard to sound intelligent.

Buffett on Ace:

Ace Greenberg does almost everything better than I do—bridge, magic tricks, dog training, arbitrage—all the important things in life. He so excels at these that you might think it would give deep inferiority complexes to his colleagues. But if you think that, you don’t know much about his colleagues.

In this book we finally learn where all this wit and wisdom—and there’s plenty of both—come from: Haimchinkel Malintz Anaynikal. (I used to have trouble pronouncing his last name until I learned that the trick is to rhyme it with Ahaynikal.) Haimchinkel sees all, knows all, and tells all—but only through Ace, his Designated Oracle here on earth.

Haimchinkel is my kind of guy—cheap, smart, opinionated. I just wish I’d met him earlier in life, when, in the foolishness of youth, I used to discard paper clips. But it’s never too late, and I now slavishly follow and preach his principles.

Many years ago, “Where Are the Customers’ Yachts?,” through a humorous look at Wall Street, dispensed some of the best investment advice ever written. In this book, Ace has applied the same treatment to managerial advice with equal success.

A Plain English Handbook: How to create clear SEC disclosure documents

Published by the SEC (1998) — Spearheaded by its Chairman, Arthur Levitt.

Buffett has long championed clarity as a core component of trust. For decades, he’s called out the obfuscation common in corporate disclosures and earnings reports. In his foreword to the SEC’s Plain English Handbook, he lends his name to a movement aimed at making financial communication more transparent and human.

He explains that effective writing isn’t about dumbing things down—it’s about respect. Buffett’s metaphor of writing to his sisters—intelligent, but not financial professionals—is now legendary. This principle applies far beyond accounting: speak so others can understand, and you invite trust. Obscure language isn’t just confusing—it’s a red flag.

Buffett on writing:

This handbook, and Chairman Levitt’s whole drive to encourage “plain English” in disclosure documents, are good news for me. For more than forty years, I’ve studied the documents that public companies file. Too often, I’ve been unable to decipher just what is being said or, worse yet, had to conclude that nothing was being said. If corporate lawyers and their clients follow the advice in this handbook, my life is going to become much easier.

There are several possible explanations as to why I and others sometimes stumble over an accounting note or indenture description. Maybe we simply don’t have the technical knowledge to grasp what the writer wishes to convey. Or perhaps the writer doesn’t understand what he or she is talking about. In some cases, moreover, I suspect that a less-than-scrupulous issuer doesn’t want us to understand a subject it feels legally obligated to touch upon.

Perhaps the most common problem, however, is that a well-intentioned and informed writer simply fails to get the message across to an intelligent, interested reader. In that case, stilted jargon and complex constructions are usually the villains.

This handbook tells you how to free yourself of those impediments to effective communication. Write as this handbook instructs you and you will be amazed at how much smarter your readers will think you have become.

One unoriginal but useful tip: Write with a specific person in mind. When writing Berkshire Hathaway’s annual report, I pretend that I’m talking to my sisters. I have no trouble picturing them: Though highly intelligent, they are not experts in accounting or finance. They will understand plain English, but jargon may puzzle them. My goal is simply to give them the information I would wish them to supply me if our positions were reversed. To succeed, I don’t need to be Shakespeare; I must, though, have a sincere desire to inform.

No siblings to write to? Borrow mine: Just begin with “Dear Doris and Bertie.”

Family

Giving it All Away: The Doris Buffett Story

By Michael Zitz (2010) — Michael is an American author. This book is a biography of Doris Buffett, Warren’s sister.

In this deeply personal foreword, Buffett reflects on his sister Doris—not just as a philanthropist, but as someone who turned giving into a life’s mission. He praises her for going beyond financial donations to form real relationships with the people she helps. Unlike many, she doesn’t just give—she engages, sacrifices, and sustains.

Buffett draws a sharp contrast between performative philanthropy and the kind Doris practices—personal, persistent, and often anonymous. He traces her values back to their father, Howard Buffett, whose love and belief in his children shaped each of their paths. This is a foreword about family, legacy, and the quiet kind of heroism Buffett holds in highest regard.

Buffett on his sister:

My sister, Doris, is a philanthropist, but far from an ordinary one. Some people write a large number of checks; others invest a large amount of time and effort. Doris does both. She’s smart about how she does it as well, combining a soft heart with a hard head.

Doris wisely employs a multiplier factor in her philanthropy, getting others—an army of “Sunbeams”—to aid her. These troops don’t enlist for pay, but rather are inspired by Doris’ goal of helping those who have suffered bad breaks in life and have had their plight ignored by others.

If you’ve created your own problems, don’t bother to call Doris. If some undeserved blow has upended you, however, she will spend both her money and time to get you back on your feet. Her interest in you will be both personal and enduring.

I’ve never believed that in philanthropy, merit should be measured by dollars expended. Lower-income individuals dropping a few dollars into a collection plate every Sunday are likely giving up something their families would enjoy—a more extensive vacation, improvements to their home or the like. Real sacrifice is involved.

To the contrary, neither I nor my children have ever foregone a purchase because the money needed for it was instead allocated to philanthropy. Our gifts, however large, have never impinged on our lifestyle.

Doris, by no means, lives a spartan life. But she does give away money that, were it used personally, would make her life easier. She is one of the rare well-off individuals who reduces her net worth annually by making charitable contributions. She thus marginally reduces her own standard of living so that she can vastly improve the quality of life for thousands of others. For Doris, a lot of good for others takes precedence over small amounts of good for herself.

More than a century ago, Andrew Carnegie wrote his famous Gospel of Wealth, concluding, “the man who dies rich dies disgraced.” Carnegie eventually walked his talk, but only after dallying a bit. At seventy-five, he had given away less than half of his fortune, either because of a supreme optimism about his health or because he enjoyed tempting fate. (He then avoided “disgrace” for all time by making a huge gift to the Carnegie Corporation.) Doris, it should be noted, has followed Carnegie’s dictum far more religiously. If she has her way, the last check she writes will be returned to the payee with “insufficient funds” stamped on it.

I don’t want to close without telling you about what I believe started Doris on this path. She—and our sister, Bertie, and I—were educated by a wonderful man, our father, Howard Buffett. His love for us was unlimited and unconditional. He encouraged us to go our own way, instilling in each of us a confidence in our potential. The route Doris has taken would please our father beyond measure.

40 Chances: Finding Hope in a Hungry World

By Howard Buffett (2014) — Howard is Warren’s son.

Buffett opens this foreword with a father’s candor. Howard—his middle child—was never going to follow a traditional path. Instead, he carved out a mission of his own: to tackle global hunger and poverty through a combination of philanthropy and farming. Buffett sees this book not just as a memoir, but as a practical guide to high-impact, hands-on giving.

He celebrates Howard’s willingness to take risks, fail, and keep going. Rather than idealize his son’s journey, he emphasizes its lessons: think long-term, stay grounded in data, and never underestimate the value of soil. At heart, this is a father’s expression of pride—for a life spent trying to make luck matter less for others.

Buffett on his son:

My late wife, Susie, and I had our first child soon after we were married—though not, she would want me to add, so soon as to raise questions in that more judgmental era. We named her Susie as well, and she proved to be such an easy baby to handle that we quickly planned for another child. The difficulties of parenthood, my wife and I concluded, had been vastly overhyped.

And then Howard Graham Buffett arrived seventeen months later in December 1954. After a few months of coping with him, Susie Sr. and I decided an extended pause was essential before our having a third (and last) child, Peter. For Howie was a force of nature, a tiny perpetual-motion machine. Susie had plenty of days when she felt life would have been easier if she had instead given birth to some boring triplets.

Howie was named after two of my heroes, men who remain heroes to me as I write this almost six decades later. First, and forever foremost, was my dad, Howard, who in his every word and act shaped my life. Ben Graham was an obvious choice as well, a wonderful teacher whose ideas enabled me to accumulate a large fortune. Howie began life in big shoes.

Through Howie’s early years, I had no idea as to what direction his life would take. My own dad had given me a terrific gift: he told me, both verbally and by his behavior, that he cared only about the values I had, not the particular path I chose. He simply said that he had unlimited confidence in me and that I should follow my dreams.

I was thereby freed of all expectations except to do my best. This was such a blessing for me that it was natural for me to behave similarly with my own children. In this aspect of child raising—as well as virtually all others—Susie Sr. and I were totally in sync.

Our “It’s your life” message produced one particularly interesting outcome: none of our three children completed college, though each certainly had the intellect to do so. Neither Susie Sr. nor I were at all bothered by this. Besides, as I often joke, if the three combine their college credits, they would be entitled to one degree that they could rotate among themselves.

I don’t believe that leaving college early has hindered the three in any way. They, like every Omaha Buffett from my grandfather to my great-grandchildren, attended public grammar and high schools. In fact, almost all of these family members, including our three children, went to the same innercity, long-integrated high school, where they mixed daily with classmates from every economic and social background. In those years, they may have learned more about the world they live in than have many individuals with postgrad educations.

Howie started by zigzagging through life, looking for what would productively harness his boundless energy. In this book, he tells of how he found his path and the incredible journeys that resulted from his discovery. It’s a remarkable tale, told exactly as it happened. As Howie describes his activities—some successful, others not—they supply a guidebook for intelligent philanthropy.

Howie’s love of farming makes his work particularly helpful to the millions of abject poor whose only hope is the soil. His fearlessness has meanwhile exposed him to an array of experiences more common to adventurers than philanthropists. Call him the Indiana Jones of his field.

It’s Howie’s story to tell. I want, however, to add my own tribute to the two women who made him what he is today: a man working with passion, energy, and intelligence to better the lives of those less fortunate. It began with his remarkable mother. Fortunately, the genes from her side were dominant in shaping Howie.

Anyone who knew Susie Sr. would understand why I say this. Simply put, she had more genuine concern for others than anyone I’ve ever known. Every person she met—rich or poor, black or white, old or young—immediately sensed that she saw him or her simply as a human being, equal in value to any other on the planet.

Without in any way being a Pollyanna, or giving up enjoyment in her own life, Susie connected with a multitude of diverse people in ways that changed their lives. No one can match the touch she had, but Howie comes close. And he is on a par with her in terms of heart.

Howie nevertheless needed Devon, his wife of thirty-one years, to center him. And that need continues. Much as Susie provided the love that enabled me to find myself, Devon nurtures Howie. Both he and I were not the easiest humans to deal with daily and up close; each of us can pursue our interests with an intensity that leaves us oblivious to what is going on around us. But both of us were also incredibly lucky in finding extraordinary women who loved us enough to eventually soften our rough edges.

His mother’s genes and teachings—usually nonverbal but delivered powerfully by her actions—gave Howie his ever-present desire to help others. In that pursuit, his only speed is fast-forward. My money has helped him carry out his plans in recent years on a larger scale than is available to most teachers and philanthropists. I couldn’t be happier about the result. Most of the world’s seven billion people found their destinies largely determined at the moment of birth. There are, of course, plenty of Horatio Alger stories in this world. Indeed, America abounds with them. But for literally billions of people, where they are born and who gives them birth, along with their gender and native intellect, largely determine the life they will experience.

In this ovarian lottery, my children received some lucky tickets. Many people who experience such good fortune react by simply enjoying their position in life and trying to ensure that their children enjoy similar benefits. This approach is understandable, though it can become distasteful when it is accompanied by a smug “If I can do it, why can’t everyone else?” attitude.

Still, I would hope that many of the world’s fortunate—particularly Americans who have benefited so dramatically from the deeds of our forefathers—would aspire to more. We do sit in the shade of trees planted by others. While enjoying the benefits dealt us, we should do a little planting ourselves.

I feel very good about the fact that my children realize how lucky they have been. I feel even better because they have decided to spend their lives sharing much of the product of that luck with others. They do not feel at all guilty because of their good fortune—but they do feel grateful. And this they express through the expenditure of their time and my money, with their part of this equation without question the more important.

In this book, you will read about some of Howie’s extraordinary projects. Forgive a parent when I say I couldn’t be more proud of him, as would his mother be if she were alive to watch him. As you read his words, you will understand why.

If you got this far, thank you for reading! I hope you enjoyed—and maybe even learned a thing or two. And once again, I will be in Omaha for Berkshire’s Annual Meeting this weekend. If you would like to try and meet up, or are hosting any events I can attend, please email me at kevin@12mv2.com or DM me on Twitter.

One for your weekend cuppa

https://caffeinatedcaptial.substack.com/p/sunday-big-think-capitalisms-last