Welcome to another Free Friday! Today’s post is a guest essay by Altos Ventures Director of Research Nick Chow. Before joining Altos, Nick was a quant at Wellington in their Investment Science division.

Nick actually just reached out to me after my Jack McDonald and Mike Shanahan letter to share his experience in the class, and we hit it off. He’s also my collaborator for my “Friday Five” series, where we’ve covered our favorite first shareholder letters, tactical startup books, culture handbooks, and college admissions essays.

PS/ Still working on the Jack essay, so if you have taken Jack’s class and would be willing to share your experience in it (on background and not to be quoted is fine), please respond to this email or send me a new one at kevin@12mv2.com. Twitter DMs work too.

Some discoveries arrive wearing lab coats; others arrive barefoot, armed with chalk and impossible claims. Nick’s latest essay explores how world-shapers like Ramanujan, Galileo, and Monet were nearly written off, and why our era is no less vulnerable to that mistake. He introduces the “pope hat paradox,” a mental model for understanding why the extremes of stupidity and genius masquerade as twins. By reverse-engineering historic false negatives, Nick offers a toolkit for investors, founders, and curious readers determined not to miss the next spark of transformative insight.

The pope hat paradox

How do you tell the difference between genius and lunacy?

A young man sat by a dusty street, chalk in hand, lost in a world of numbers while other children sprinted past. Over the years, he wrote countless letters to European mathematicians, yet none were ever answered. His strange notation was too inscrutable to take seriously. Yet fate intervened: one eminent scholar recognized the brilliance hidden in those symbols and exclaimed, “We must bring this man to Cambridge immediately!”

That man was Srinivasa Ramanujan — one of the greatest mathematicians in history, whose genius almost went unnoticed.

I often think about how many experts passed on Ramanujan, before G.H. Hardy finally realized that they had skipped over genius and hurriedly arranged for him to come to Cambridge.

How many Ramanujan's have we missed?

A history of overlooked genius

It's incredibly difficult to tell the difference between genius and stupidity before-the-fact.

One of my hobbies (and also my professional work) revolves around studying decision-making. In particular, I've been fascinated with people who have performed incredible, society-shifting feats. These people are typically iconoclastic and think differently, which allowed them to change the world — as investors would say, they were both contrarian and correct.

"If you want to have better performance than the crowd you must do things differently from the crowd." — John Templeton

The difficult truth is that sometimes the actions of incredibly brilliant people were not so clearly agreed upon as brilliant at that point in time.

Galileo: In addition to a variety of other incredible discoveries, Galileo published telescope data confirming that the Earth orbited the Sun, as opposed to the common belief that the Earth was the center of the universe. After a lengthy series of trials, the Catholic Church accused him of heresy and sentenced him to house arrest (where he later died).

Monet: Monet faced harsh opposition from the Parisian art community for his new artistic style. His style of loose brushwork and emphasis on light and color was regarded as sloppy and unfinished. However, we now call this style Impressionism and dedicate entire museum wings to his artistic legacy.

Duke of Wellington: Arthur Wellesley was an English commander who was often criticized by his contemporaries as slow and lacking force in his campaigns. Then, using the same strategic approach, he defeated some French general named Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. Afterwards, everyone now considered him, the Duke of Wellington, a genius.

If history has shown anything, we have a collective inability to recognize genius.

The pope hat paradox

"You can't connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards." — Steve Jobs

This confusion between genius and foolishness is everywhere.

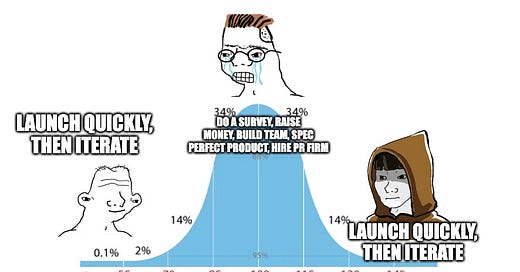

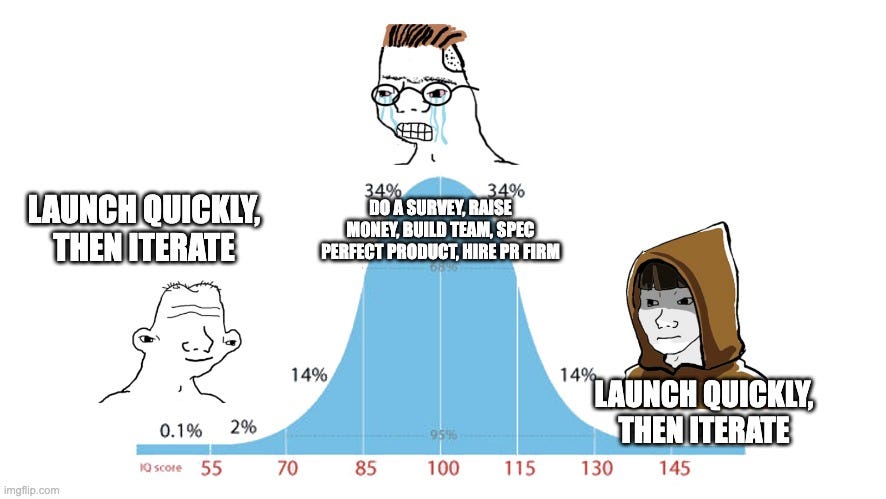

If you've been on the Internet for any period of time, you're likely to have stumbled upon some variant of the midwit meme:

The midwit meme demonstrates a fundamental truth: the stupid thing to do often looks the exact same as the thing a genius would do.

The fancy way of saying this: the line between genius and stupidity is incredibly difficult to discern ex ante.

I call this the pope hat paradox. Why?

Because it’s nearly impossible to tell genius from stupidity before the fact, you can take the midwit distribution and connect the two tails together, and then it forms a manifold that looks like a pope's hat (the real name is a mitre, but that's too hard to remember). There's also an underlying irony in that Galileo's brilliant discovery was suppressed by the Pope and the Catholic Church, but I digress.

And before we laugh at all our historical ancestors for being ignorami and suppressing great ideas, I guarantee that we are guilty of the same mistake today. There's some collection of Galileo's out there, living among us and striving to share their work, but being laughed out of the room (at least we generally don't do banishment and house arrest for divergent ideas anymore). Three hundred years in the future, I'm sure our ancestors will be laughing at us for being so close-minded and foolish. But the joke is on them — the people in 2524 will be laughing at all of us!

But then I return to the original question: how do we make sure that we don’t miss the next Ramanujan, Galileo, Monet, or Duke of Wellington — the next genius hiding in plain sight?

Heuristics for identifying genius

How do I figure out if someone is actually a genius or someone to ignore?

People have different heuristics for this, often focusing on some degree of eccentricity. But if the founder you’re talking to only wears black turtlenecks, 50% of the time you’ll be talking to Steve Jobs and the other 50% of the time it will be Elizabeth Holmes.

The short answer is that there's no certain way to do this, but here are some heuristics that I've developed over time.

Check myself before I wreck myself

The most important condition is to understand whether I even know enough about the underlying subject area to evaluate whether someone is a genius.

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.” — Richard Feynman

Sure, I aced my stoichiometry conversions in tenth grade, but that's pretty much the limit of my knowledge of chemistry. Given my (lack of) knowledge in chemistry, I don't think I'd be able to identify the next chemistry Nobel laureate even if I spent a few hours with them.

If Ramanujan had sent me his letters in the early 20th century, I wouldn't have had the ability to recognize the genius staring me in the face.

There are certain areas in which I have truly world-class expertise in, a few more in which I am quite knowledgeable about, and infinitely many of which I know little to nothing about. My skill in differentiating between genius and stupidity outside of my circle of competence is likely minimal, so I try to stay away from these places.

Demonstrated competence

If a smart and otherwise thoughtful person (with demonstrated competence in other domains) is talking about something that sounds initially a bit crazy, I've found that this is a good place to dig. This certainly doesn't mean that I immediately believe them, but it indicates something potentially worth digging on.

Countless innovations have been ported from other fields by other experts. The reason this happens is because experts who specialize in certain fields are often vulnerable to the Einstellung effect: the tendency for problem-solvers to employ only familiar methods even if better ones are available.

"Rice professor Erik Dane finds that the more expertise and experience people gain, the more entrenched they become in a particular way of viewing the world. He points to studies showing that expert bridge players struggled more than novices to adapt when the rules were changed, and that expert accountants were worse than novices at applying a new tax law. As we gain knowledge about a domain, we become prisoners of our prototypes." (57, Originals, by Adam Grant)

The old guard ferociously guards its sacred truths, which suppresses many of the disruptive ideas from the budding upstarts. Generally, radical ideas can’t hope to convince the dominant expert class.

After all, this is what physicist Max Planck meant when he observed: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die.”

Or said another way, science advances one funeral at a time.

But this isn’t the same thing as saying all novel ideas are groundbreaking— you can't just pull a random person off the street and ask them their opinion on a super complex topic. I include the qualification that the person is a high-performer from another domain, because this high-performance typically requires people with the ability to develop nuanced understandings of complex systems. My implicit assumption is that their demonstrated capacity gives them the ability to wrangle with this new field, rather than relying on gross oversimplifications of nuanced topics.

To verify this further, I often will ask them to describe the existing landscape of cutting-edge knowledge in this domain. If they're able to answer this well, then we can proceed to discussing how their new discovery contradicts or builds from the current understanding of the field.

Too often, accomplished thinkers who are new to a field will believe they have discovered something new, but then later realize that someone already invented that technique thirty years ago. In particular, I've seen this so many times in quantitative finance: some sharp CS grad learns about quantitative trading and shows me a "new and novel strategy guaranteed to print money," and then I tell them they've re-invented a trading strategy the industry has known about since the 1980s. It's a little sad to see how quickly some people's dreams of Italian supercars and butlers deflate, but unfortunately it is really hard to come up with truly novel ideas!

However, if I meet a new entrant who has an incredibly good grasp of the existing field (an uncannily knowledgeable new entrant of sorts), and then they also start talking about some new radical ideas in the field, I'll be the first to listen.

With genius comes eccentricity

I've been fascinated with studying great talents throughout history, and the constant seems to be that all of them are at least a little bit quirky.

In addition to his fundamental breakthroughs in physics and mathematics, Isaac Newton spent a good portion of his life working on alchemy, with around 10% of his writing devoted to the subject.

Paul Erdos was one of the most prolific mathematicians in the 20th century (look up the Erdos number). He also spent most of his career with no permanent home or job, and would unexpectedly show up at the doors of fellow mathematicians to collaborate (and temporarily co-habitate) with them.

We all know that Mozart was a brilliant composer. Did you know that he wrote “toilet humor” pieces too?

You can argue as to whether genius is necessarily accompanied by weirdness, because it takes some level of divergence to come up with anything novel. Perhaps people's enhanced social status as a genius allows them to do whatever weird stuff they please. Or maybe it's a more complex underlying phenomenon.

I think it's as simple to say that extreme people get extreme results.

The values test

Sometimes I'll meet someone who passes all the previous checkpoints, but I'll still stay away. Most of these times, it's because of a mismatch in values.

Charlie Munger describes it best: You should aim to work with people who have high intelligence, high energy, and high integrity — if someone is incredibly smart with low integrity, it just means that they will figure out more clever and creative ways to screw you over.

I can't hope to enumerate all of those integrity red flags that scare me away — sometimes it's watching them treat other people who they see as lower than themselves (sadly common) or sometimes it's just a flippant comment.

But life is too short to spend with people you don't respect, no matter how much of a genius they might be.

The magic formula

Yet after all this, I still don’t have a guaranteed checklist for identifying the next Ramanujan or Galileo. By definition, these individuals defy conventional wisdom.

What I do know, though, is that it pays to keep an open mind, especially when confronted with someone who has both a deep grounding in their field and a willingness to break from its orthodoxy. Genuine genius rarely arrives neatly packaged in normalcy.

Of course, a willingness to challenge convention isn’t enough on its own; we must also look for alignment in values and integrity. As Charlie Munger pointed out, intelligence and energy without integrity is a recipe for disaster. Geniuses can change the world for the better, but the lack of any moral compass can change it for the worse.

So, how do we make sure we don’t miss the next Ramanujan?

We stay curious, we stay humble about our own blind spots, and we refine our capacity to distinguish big ideas from fool’s gold. We partner with those who meet both our standards of brilliance and our standards of character.

There’s no perfect formula — some degree of faith and risk is unavoidable. But if we remain vigilant, ask the right questions, and remain open to the possibility of the extraordinary, perhaps we can connect the dots without waiting for history to do it for us.

How will you recognize the next genius when they show up at your doorstep?

Thank you to Vivian Yu for reviewing earlier drafts of this piece.

If you’d like to read more of Nick’s writing, you can do so here: