Letter #106: Reed Jobs (2022)

Founder of Yosemite & MD of Emerson Collective | Leading the Future of Biomedical Innovation

Today’s letter is the transcript of a conversation between Reed Jobs of Yosemite (then at Emerson Collective) and Lloyd Minor, the Dean of the Stanford School of Medicine. In this conversation, the pair discuss how the virtual world has affected the healthcare industry, what we can learn from the tech revolution, the loss of trust in scientific institutions, why we need to be more open about uncertainty, developing new therapies and diagnostics and bringing them to patient care, hotbeds of innovation outside the US, Theranos, liquid biopsies and fraud, lessons from Steve Jobs on being honest with your customers and your people, leveraging philanthropy and funding to tackle threads from cancer to Covid, and building a biomedical ecosystem capable of deploying new technologies to solve the future’s most pressing problems.

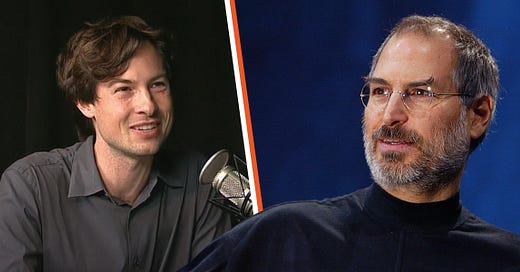

Reed Jobs is the Founder of Yosemite, a venture capital firm focused on new cancer treatments. Reed first started developing an interest in the cancer space at the age of 12 when his father was diagnosed with cancer. He had his first internship at Stanford when he was 15, and later enrolled at Stanford as a pre-med student. However, after his father passed away, he switched majors to history. After completing a master’s degree there, he returned to the field of cancer by taking over the reins of Emerson Collective’s healthcare division, which invests in companies and provides grants to labs. At Emerson, his sole focus was on oncology, with his team laser-focused on accelerating the discovery and translation of cancer research to best improve and empower the lives of patients. Just last week, he announced the launch of his new fund, Yosemite, which will run a for-profit business that also maintains a donor-advised funds, which he believes will create a virtuous cycle for innovation.

I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did!

(Transcription and any errors are mine.)

Related Resources:

Transcript

Lloyd Minor: Leadership. All my life, I've been fascinated by what makes a good leader or good leaders born or made, can leadership be taught? How do leaders lead if people don't trust to even listen? I grew up in Arkansas. Now I live and work in the innovation heartland of Northern California. During these last years of constant crisis, I've thought more deeply about what leadership is and what it takes to lead people, especially when trust is in limited supply. That's why I decided to create this podcast and reach out to changemakers from different disciplines to hear what they have to say. As the host of this show, the most important things I can do are two things I learned in medical school to ask good questions. And then listen.

Lloyd Minor: Hello, I'm Lloyd Minor, Dean of the Stanford School of Medicine. And welcome back to the Minor Consult. I'm delighted to welcome this week's guest, Managing Director of Health for Emerson Collective, Reed Jobs. I'm privileged to have known Reed for a number of years. While at Emerson Collective, he's used various tools--philanthropy, investment, advocacy, and community engagement--to improve human health. Reed's primary focus is cancer, a disease that robbed him and the world of his brilliant father, Apple cofounder, Steve Jobs, a decade ago. Though just 30 years old, Reed has already made his mark as a leader, employing a data driven approach to building organizations, businesses, and policies tackling society's most pressing challenges. It's my pleasure to welcome Reed Jobs. Reed...

Reed Jobs: It's great to see you Lloyd! I am just so happy to be in person again. It is, it is really, it's been so overdue. All of us are really doing our best in our virtual worlds, but really being able to be face to face is kind of uncomprable.

Lloyd Minor: It totally is. I've really missed that. It's been... I think there's some things that we've learned from Zoom that maybe we continue, I think symposia work really pretty well, overall, on Zoom and everything. But doing hiring or really building relationships is just impossible without being face to face.

Reed Jobs: Recruiting is hard.

Lloyd Minor: Yeah, yeah. How have you done with... you're still, you're investing, obviously. You're constantly interacting with entrepreneurs, and with universities and grant recipients. How has this virtual world affected you and what you're leading at Emerson?

Reed Jobs: Yeah, it's a super interesting question, Lloyd. On the one hand, I think it's been, in some ways, really positive for the healthcare industry. It has accelerated a lot of underlying trends, particularly around telemedicine and care in the home, that I was, that we've seen happen, we've seen, I remember, 2018, 2019, my team and I were talking about this kind of new thing called remote clinical trials, and how long it was going to take for adoption to happen, and for these pharma contracts to be put in place that would really allow this to scale, and COVID acted as this, just unbelievable accelerant for that, because immediately, you couldn't have trials in hospitals anymore. So all these companies had to scramble to figure out how they could do it remotely, how they could do that in a cost efficient way. And a whole crop of companies really came up to service these needs. And what's really great is that the contracts, the pharma science for clinical trials, since they're very long, are five, six year contracts. So these companies are now really well financed and capitalized, and the norms have really switched. And I think that's the most powerful thing. People are now really comfortable signing up online. And why I care about this so much is that it is a tremendous development towards accessibility, because there used to be, you used to have to go to mostly academic centers for trials. And of course, you work here at Stanford, and Stanford's wonderful, but people... you have to drive a lot in the Bay Area. People would have to drive in four or five hours away from Sacramento sometimes, and you'd have to get your own lodging. And for a lot of people, that is a prohibitive cost. So being able to do it remotely now, and interface with your local provider, means that so many more people, so much more easily, can access clinical trials. And that that's just been a huge development that I'm really, really happy about. But for us, personally, I've had to cancel a lot of site visits. And recruiting over Zoom has not been the easiest thing in the world. So getting getting that back is something I'm very excited about. I do try to do a little bit of cheating and asking people to meet for coffee outside or whatever folks are comfortable with. And we do a little bit on the side like that. But that's sort of been the best of a bad situation, I think.

Lloyd Minor: Exactly. I first met you when your interests in science and cancer were just budding. And it's been so wonderful to see how they've evolved and how much impact you've had in a relatively short period of time. You know this space really well now, Reed, in cancer. What's most exciting for you, both in the general grants you're receiving, and also in the investing you're doing? And sort of in your crystal ball, which may be for all of us has been a bit cloudy these past couple of years, but in your crystal ball, where do you think we'll be 5-10 years from now, because of the investments in people and programs that you and Emerson and others are making in the cancer space writ large?

Reed Jobs: Candidly, I think these next 5-10 years are going to be the most exciting that we've ever seen in biotechnology. And that's a strong statement. But I actually really believe that, because we've seen advancements in gene editing and in immunotherapy that are totally unprecedented. And like I said earlier, are largely in their infancy. There's a few next stages that that need to be discovered and optimized, but there's so much great intellectual power being put into them that I have a lot of confidence that, in terms of gene editing, delivery and solid tumor targeting for CAR-Ts and other immunotherapies, we're gonna see some real traction the next 5-10 years. So if I had to put my little prediction hat on, I would say, confidently, that I think we're going to see some real solid tumor efficacy from some exciting solid tumor targeting immunotherapy companies in the next five years. And that is such a big deal. It's worth zooming out to say, Holy cow! We're actually going after the majority of cancers with the next generation of therapies. And this is just the beginning. Nothing else has really ever been able to, at scale, take care of stage four cancers before CAR-Ts have. We've had a few targeted therapies with a few lucky cancers that have low hanging mutations that they're addicted to, but besides that, it's pretty... there's not a lot to be that proud of. That's really changing. So I think seeing some of those clinical trials coming out is one of the things I'm the most excited about. On the other hand, from a research point of view, I think where we're going to go with gene editing for genetics and epigenetics is going to be really, really exciting in the next 5-10 years. It's an area that's still very young and new, and there's really so much that needs to be optimized in terms of making it a lot safer, making it a lot more efficacious. It's not ready for humans yet. But I think we're definitely going to start to get a lot more safety data. And I'm really, really excited for what that's going to mean for a lot of diseases, particularly rare diseases.

Lloyd Minor: I agree with you the next 5-10 years are going to be the most exciting we've ever seen in life sciences writ large, and hopefully the next 5-10 after that even more so. Why don't we make sure that we leverage it most effectively, that the opportunities we have are maximized and the people who are doing the work are maximally successful?

Reed Jobs: It's a really interesting question. That is a point of view that medicine has not always brought to the fore, and I think, to its detriment. So what I really hope to see, at the very least, is that we get a lot smarter about clinical trials that represent the the entire population instead of just the population of a particular locality or of a particular zip code. So we talked earlier about how remote clinical trials are much more accessible and have been widely adopted in the last year. That's also going to change who gets access to treatments and who treatments are earmarked for. As you know, recently, for the first time, I think this was two years ago, the FDA released a guidance for cancer therapy not based on your cancer type, but based on your genotype. This was for MSI-H colorectal patients, or sorry, just for MSI patients across the board instead of just for colorectal patients. And I think that is a really overdue designation. But that's something that's going to, I hope, become more and more commonplace, particularly with certain immunotherapies targeting mutational categories instead of just particular cancer types in particular. So, I really think that means treatment, particularly in oncology, is going to become a lot more personalized. And I think that's just going to be a different way that it's going to be treated and reimbursed. And I hope that that will lead us to much, much better outcomes.

Lloyd Minor: You know, Reed, you grew up with a lot of technology. Your father certainly led the way in consumer technology and the democratizing effects of technology. And yet, we, as you've mentioned already, we have a ways to go in medicine and healthcare, don't we? In terms of the inequities that exist, and that have been exposed during COVID in particular. How can we learn from what has worked in technology? And you talked about clinical trials, for example, and deploying technology to really extend the reach of clinical trials, but what other things can we learn from the tech revolution that we ought to be taking into account as we build the biomedical revolution?

Reed Jobs: That's a great question, Lloyd. There's definitely a lot of scar tissue there, isn't there? I think one of the most important things we can learn is that we need to really, really respect people's privacy. And we need to give them the power to determine who has access to their data and what that's used for. So, it's interesting, when you look at healthcare, clinical records, and most data that flows through hospital systems, it is absurdly balkanized. And the user interface is atrocious. And it's kind of this surreal experience, honestly, because we live in a wonderfully high tech world, and particularly here in Silicon Valley, yet when you go to a hospital, even a great hospital like Stanford, it's like you're stepping back in a time machine 30 years. And the software there is, nothing against there, the software is not very good. The user interface isn't very good. And it's this... departments can't talk to each other, and you can't transfer data, and people give you a floppy disk with things on it. And it's like this anachronistic little time machine. It's crazy. So I think one of the most interesting things that's going to happen in healthcare in the next kind of 20 years is seeing it really catch up with the rest of the world from a technological point of view. Just both from a data infrastructure, interoperability, and UI aspect. And I really hope, and luckily, this is, a lot of this is already codified in legislature like HIPAA and stuff, but people's privacy and control over that data is going to need to be paramount, as it, it currently is now, but it really needs to be a lot more electronic, and it needs to be a lot more interoperable. Again, this is something that's probably a nationwide level, whether that's through legislation or through some really innovative companies in the space, of which I think there's space for many. But yeah, we need to really shape up the infrastructure systems that we have in place, because not only are they really not helping patient care, but it's really bad for the hospital systems themselves, too. And the physicians.

Lloyd Minor: Yeah, for sure. And we still use fax machines in healthcare today, if you can believe it. But yeah. And it really gets to the issue of the decline in trust, which we're seeing in all sectors and aspects of society, I think, and... What what are your thoughts about how did we get to where we are? How do we get out of where we are? And in particular, with healthcare, that's going to be critically important, right? If... I think we're still respected, healthcare institutions are still respected, but in general, the decline in trust in science, sort of the nebulous nature of facts, recognizing that facts evolve, have brought a debate that really I hadn't seen previously. Where are we today with that? Where do you think we're going?

Reed Jobs: Lloyd, I love your questions. It has been one of the most jarring things in my lifetime, is to see not only the decay of institutional trust across America, but like you said earlier, to see a real backlash and skepticism towards a lot of what I thought was pretty well established straightforward science. And figuring out what's at the root of that, I think, is incredibly interesting. And like anything, it's a heterogeneous answer. There's no one culprit or silver bullet here. But one trend that I've certainly just seen and noticed is the amount that people are willingly dishonest and deceived. It's actually really disturbing to me. And you could chart some of this to the loss of traditional gatekeepers in the information economy, and you can debate genuinely whether or not that was a good thing to be in place or not, but I think what's an objective truth at this point is, with the loss of those, you're just seeing far more sources of information that previously would have been shut out, being able to access wide, large audiences. And... podcasting is a good example of that. It's, I think, a phenomenal new medium, and I personally am a runner and I listen to podcasts a lot. And it's a great part of my routine. But you also have to look at it honestly and think, Wow, there's... just as you get great voices like Stanford and other news organizations, you get quite a lot of crazy opinions out there. And some people take that to heart. So I don't know if there's a really easy solution for that other than people recognizing that, and being cognizant of it, and not balkanizing their news information. But the loss of trust in the scientific community, I think is really jarring and dangerous. I hope that this is something that does recede. I mean, there's interesting polls out there, if you ask people if they trust prominent physicians in, say, the US government, most people will say no. But if you ask people if they trust their doctor, like your personal doctor, almost everybody says yes. So there is a proximity issue here, clearly. And luckily, the entire system, certainly when it's one that you experience personally, is still viewed with a lot of trust. But what does bother me a lot is the loss of trust in scientific institutions, and I guess, the scientific method and process. And some of that has to do with the fact that there's just far more, I don't know if there's far more dishonesty now than there was 10 years ago, but there's certainly far more public skepticism that we can monitor. And that's just, it's just, it's disconcerting. I don't know, what do you think, Lloyd?

Lloyd Minor: I think we've done a poor job overall, of communicating science to the public. There are exceptions to that. But we need to be more... I think one thing we need to be more open about is when we don't know the answer to something. Then we simply need to say there's uncertainty. And we need to be able to convey uncertainty in a way that's meaningful. That doesn't sound like we're just trying to hedge the question. But here are the things we don't know, here's why we don't know them, and here's what we're trying to do to get the answers. And I think we need to engage more people in what the scientific method and scientific process is, and not... What we really have to avoid is seeming like we live and work in an ivory tower, wherever we are, because I think this dichotomy between people who feel like they're benefiting from the advances in society and technology and those that feel like they've left behind, that dichotomy is really dangerous to the fabric of democracy. So somehow, we have to figure out a way where the motto, the principle at Emerson, where We each do better when we all do better, we have to figure out a way that that's really meaningful for everyone to feel that they can do better because of the way society is advancing. And right now, I think they're large segments of the country that feel like the country has just left them behind, doesn't care about them. Now, we can argue, of course, that that's not factually correct and cite a lot of evidence, but it's perceptually the reality for many people, and it's affecting everything we do, I think.

Reed Jobs: Yeah, I think it's widely true. And I think it's actually not the province of one political ideology that we don't zoom out and realize that we're all rowing in this boat together. And we are sinking or sailing together. And it is very easy to disassociate from that and to not think of your own compatriots as really being on the same team. And I think that's truly been to our detriment, because we are so much more powerful united. And we are a united country. That's just a fact. And us not treating or thinking of each other like that is really dangerous. So, yeah, I heartily agree with all that.

Lloyd Minor: Back to the theme of technology and how it can be better utilized to democratize healthcare and access to care, what do you think's working right now? Each of us does have, legally, has access to our records. Many systems like Stanford have made it possible for you to download your records into various apps on Apple or other devices. The number of people who have actually taken advantage of that, even in our own system, is relatively small. And I feel like in a lot of things in our lives, we recognize we have individual responsibility for it, how we maintain our finances, and each of us does our banking online or some variant thereof, but with healthcare, even people who are quite literate and use technology in every other aspects of their lives, there's a reticence to using it in health and healthcare. What are your insights about that?

Reed Jobs: Yeah, it's a really interesting question, Lloyd, super important. My suspicion is that people are reticent to do so, as you say, because there isn't a clear utility for what that will be for. The only real reason, benefit, you could get from that, is interoperability. If you're changing hospitals and you want to just take your records and have them with you, but most people who would need to do that are probably acutely ill or a caregiver. And that's obviously a small segment of the whole patient population. I think an interesting corollary is, as mundane as it is, is a credit score history. That was something that was the province of banks for a long time, and most people didn't really think twice about it, because like, what's the utility of it? Yet, once you start having third party apps and API's being developed on that, there's a whole ecosystem around people who can mine that data, use it, you can sell it, you can do whatever the heck you want with it. But there's a lot of uses for it. And to me, that's kind of the missing part in this marketplace, honestly, is there aren't really any trusted, or, good utilities that you can plug in with your healthcare data at the moment. And some of that has to do with privacy concerns, some of that is just the fact that, like you said, it's a little chicken and egg, there aren't that many people who have these records out there so there isn't a huge incentive for people to use it. But I personally think that it's obviously a hugely important data source. Like you said, legally, it does belong to patients individually. So what they choose to do with it is totally their prerogative. And I think you could actually start gathering really large amounts of data through going to people directly, and we should make it as easy for them as possible, because it's their own, it's their gosh darn data.

Lloyd Minor: Exactly. And then how do we make it actionable? How do we link the... I think you hit on a really important point in that right now, you can access it, you can download it, but then what are you going to do with it? And do you... have we done a good enough job in explaining what it actually means? You can download your labs, but does that have meaning to people? What do we in healthcare delivery need to do to increase the meaning and the utility of the information that we hold onto and that we furnished to people if they want it? It just not many people want it, probably for the reasons you just described.

Reed Jobs: One of the most important things I think we can do is make this available to researchers. I think the data that you see in medical records, and that comes out of every hospital, is probably some of the most useful data that exists in the world. A lot of large companies are coming around to this, be that Amazon or Microsoft or other big players in the AI space. But that aside, for places like Stanford, which have incredible academic researchers, this would be a bonanza for them. From everything from outcomes research, to different treatment pathways, to all kinds of things, that if you got a lot of patient data that was anonymized, you could really start asking some very interesting questions. So I actually don't think it's reticence on the patient's part. I think it's mostly a communications issue, a trust issue, and a real question about what people's motives who are going to use the most sensitive data is for. However, like we've seen with things like tissue or organ donation, people feel very comfortable giving their data and medical history to researchers and people in medical systems.

Lloyd Minor: Yeah, yeah. We're all... you and I both, the ecosystem writ large, is really excited about the advances in life sciences, biotech... I agree with you that these next 5-10 years are going to be so exciting in cancer, in particular, solid tumors. And yet we're also confronted with a harsh reality that most of the determinants of disease are social, environmental, and behaviorally grounded. And overall, probably 70% of disease emanates in a direct fashion from those factors. And yet they are so hard to address. And we've done, particularly, I think, in our country, a relatively poor job at addressing them. How... and this, of course, fits in with with the overall portfolio of Emerson, because you're doing so much in so many areas at Emerson. But how are you thinking about how we have more impact in social, behavioral, environmental determinants in addition to the advances that are going to transform our treatment of disease once it occurs?

Reed Jobs: Great question. This has always been an area that I have been keenly interested in. Yet it's really hard to build a business in, and it's really hard to do something that is widely scalable. Everyone's metabolism, diet, sleep pattern is very, very unique. It's very individualized. And what is healthy in some populations wouldn't work with others. So building any kind of standard protocol, whether that's in dieting or lifestyle, is really, really a difficult task. And I personally think that most people have kind of gone about it the wrong way. What, at least for me, what I care about most is, Do I feel better than I did yesterday? And do I feel like I am in a healthy trajectory in my life? And of course there's a lot of different variables in that, but figuring out what my personal baseline is, and how I can optimize that is one of the more important things. And a lot of that's linked up to what we were talking about earlier with really getting a lot more healthcare data, whether that's from wearables or from patient data that is gathered at the home or remotely. But figuring out a lot more about your personal health is one of the most interesting things that's happened the last couple years. And you've seen this with a lot of consumer facing healthcare companies, whether that's things that monitor your sleep patterns, or interesting wearables around exercise or heart rate, or for diabetes. So we're actually getting a lot more activity, in particular disease areas for people who are either at high risk or who want to do that. Figuring out how to do that on a population level, I think is a much more difficult question, to be honest with you.

Lloyd Minor: Tell us about Emerson. About the goal of Emerson and the Health Division that you lead as Managing Director at Emerson, and what you're excited about right now, and what you've got coming up in the future.

Reed Jobs: Emerson's a really special organization. It's a family office and it's structured as an LLC. And that is really important because it allows us a huge amount of flexibility. So foundations are tax-exempt, but they're very restricted in what they can do in the for profit space. They can invest in things called PRIs, and MRIs, but those are very restricted. And for good reason. Ethically, you don't want foundations to be able to do a lot of investing in areas that they work in philanthropically, because that really goes against the ethical mission that they're trying to pursue. But at Emerson, we're actually able to do both, because we're not structured like that. And why that matters is that our whole view is sort of what we call tool agnosticism, which means we see a lot of problems, and some of those have market-based solutions, some of those have philanthropic solutions, and we're able to just apply whatever tool makes the most sense in the situation. And that has allowed us to engage with many more problems for many, many more angles. And I can see that really being a lot more efficacious than only doing philanthropy, which, while important, is a little narrower in what it can really accomplish. So I lead the, as you said, I lead the health division there, and we actually exclusively focus on cancer. So cancer is around half of biotech and about half of healthcare. So it's a huge chunk of that. And within that, we do both for and nonprofit investing. And our philanthropy has no strings attached. It's as pure as it can be. And that takes the form of us funding researchers, labs, projects, on a competitive basis that we do internally. So we don't just give money away, we actually have scientific advisory boards that review applications, and we try to have it be as as meritocratic and science driven as possible. We try to take the CVs off applications so we actually don't know who's is who's, we can just judge it independently. And I feel pretty confident this has allowed us to really fund some of the best science from some really, really promising scientists. And we have... we don't disclose budgets, but I can candidly say we're one of the largest cancer philanthropists in the world right now. And I am so proud of that. And that work is really something that I am really, really happy that we're going to continue for a long time. However, we also have a venture group that I run as well. And the reason for that is not because we want to go out there and make a buck, but the reason is that a lot of the same people who are great researchers are also great entrepreneurs. And Stanford has been an incredible place for that. Not only just with the spirit of building companies that we have here, but of course, you have some of the very best researchers in the world. And ultimately, what I care about is making a big difference in cancer mortality for people. And the only way you do that is by developing new therapies and new diagnostics. And I sort of see myself as a one-stop shop for doing that, from inception in labs that we help fund through philanthropy, through translation into companies, into the clinic, and into patients ultimately. And that whole journey can take 15, 20 years. But I think that I... this is really what I want to do with my life. And I can take a long view towards that. And the system that we built is able to interact with basically every single step along that product development pipeline. And we're able to do it pretty agnostically through philanthropy and venture dollars. And I'm really, really excited to say, Lloyd, that we have seen some incredible developments in new diagnostics and new therapies in the last five years. Things that were really theoretical 20 years ago, are now totally new ways to treat and diagnose cancer patients. And what's really, really exciting for me is that all these things are kind of in the springtime of their existence. They're really early on. And it's version 1.0 of a lot of these new technologies, particularly in immunotherapy, and already there's some great developments. But it's so cool to be able to see where these things are going, see them being optimized and hybridized. And I'm really, really excited to think about what the next 10 years of therapies are gonna look like.

Lloyd Minor: Understood. There's so many examples like that, aren't there? What are you most looking forward to when we're done with this COVID stuff?

Reed Jobs: Travel. I haven't left the country since since early 2020. So I cannot wait to start traveling again. That's something I really enjoy doing, both in work and for personal enjoyment. So...

Lloyd Minor: Favorite places?

Reed Jobs: Well, I have a list of countries I've never been to before, but that I really want to explore. Morocco sounds amazing! It's got deserts and ruins and mountains and like, Oh my gosh, what's not to love? New Zealand? How cool is that? It's Lord of the Rings. It's like, they didn't have to do any CGI at all. It's just, that's just New Zealand. Those two are really high up there. I'd really liked to explore Machu Picchu. I mean, I've never been to Peru, and that entire country's incredibly biodiverse, and the... just the Incan ruins there sound absolutely mesmerizing. So, yeah, those are some that I just, wouldn't be, cannot wait to go.

Lloyd Minor: That sounds great. And I agree. I haven't been out of the country either. And, gosh, I can't remember, is it... long before COVID? But I'm looking forward to it too. What areas around the world are you most excited about scientifically, in terms of of the research you're supporting, or the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Where outside of the United States do you think are the hotbeds for innovation today?

Reed Jobs: In the medical space, the places I work in the most outside of the US are Israel and the UK, both of which I am really excited about, but it's interesting. They both have very different strengths. Israel, unsurprisingly, is incredibly entrepreneurial, and has really, really great universities, the Weizmann Institute, Tel Aviv, really great universities, top tier. But of course, Israel is a very, very small country. Punches above its weight in a lot of ways, but it's a small market company, and any healthcare company that gets big will ultimately have to migrate to the US, almost every foreign company does. So, being a good conduit for some of those early stage startups has been really fun. And I've supported some research in Israel for a while, just because it's incredibly high quality, and that's just a... it's a very, very scientifically great country. So Israel's high up there for sure. The second one, of course, is the UK. And, again, top tier universities. Working with some folks at Oxford has been great. I've done that for a long time. Worked with people at Cancer Research UK, which is their main charity. Unlike the US, they don't have an NIH, they actually have to source almost all of their research dollars from donors. And crazily enough, they have a budget of around 600-800mn pounds per year, which is mostly solicited by donations, and the average donation size is under 50 pounds. So it's a ton of small dollar donations which really funds most of their research, which I think is just kind of incredible. It's amazingly generous. But what's also interesting about the UK is, after Brexit, the current conservative government has really identified healthcare as the place that they want to invest a lot of government and private resources. They sort of want that to be the marquee element of the post-Brexit British economy. And they've talked a lot about that, and there hasn't been as much shovel in the ground, quite yet. But it's really interesting to see what they're going to be doing there. And that's just one that they've prioritized it a lot. They have incredible ingredients from academics to great entrepreneurs, and yeah, Britain has been a really fun one to work with.

Lloyd Minor: That's great. Other things we should cover today? That you'd like to cover?

Reed Jobs: Let's keep talking. Let's get some extra stuff.

Lloyd Minor: That's great. That's great. Good.

Reed Jobs: I got time. I probably had a few crazy things in there.

Lloyd Minor: No, I think I think it's been great.

Reed Jobs: Alright, Lloyd. This has been a little unidirectional here. What has been the most exciting thing that you've learned in the past year?

Lloyd Minor: I think the most exciting thing I've learned is the power of people. I mean, I've always known it. Every successful enterprise, whether or not it's a university, an academic medical center, a company, everything comes from the people in it. And certainly that's been true during COVID. I've been so impressed, inspired, motivated, by the incredible people that I work with everyday. At Stanford, mainly, but also here in the Valley and more broadly around the country. I think, whereas, we talked earlier about how COVID surprisingly, and concerningly, has driven us apart as a society in the country, I think in healthcare and science and at universities like Stanford, it's actually brought us together in very powerful ways. And that's been inspiring to me and certainly has changed my outlook, both during this crisis, but also far beyond it. I've always felt and known that what we do is about people, but that's never been more evident than then during these past 22 months.

Reed Jobs: Well, here's one... you asked about other areas that I'm excited about. We talked a lot about next gen immunotherapy, which is so huge. And it really represents I think, one of the huge leaps forward that we've ever had in medicine. But another really important one is in liquid biopsies. And Stanford has been a real cradle for that, with Ash Alizadeh, Max Dean, a lot of great researchers here who have done pioneering work there. And recently, of course, there was a bit of a high profile case with Elizabeth Holmes around Theranos, who claimed, of course, falsely, crazily, to be able to take out samples of, on a few blood drops, to test a whole raft of diagnostic things, including some cancer markers, I believe. And while that company is a marquee example of fraud, and I am happy that the jury decided the verdict as it did in her case, it has been an interesting thing to see in the last five years, that a lot of the principles of liquid biopsies, while her company was a clown show, is actually quite real, and is really, really kind of coming into the market in a pretty full bloom right now. And we're seeing that with a lot of companies doing extracellular DNA monitoring in the blood, RNA monitoring proteins... it takes more than a couple of drops, unfortunately, but it's a really powerful technology with a lot of great sensitivity right now, to pick up not only some cancer markers, but also infectious disease markers, and a whole raft of other things. So one other area that I think I'm really keen to see develop more in the next five years is liquid biopsies. Is that an area that you also think is going to be equally transformative?

Lloyd Minor: Oh, for sure, for sure. And we've talked a lot about that. I think just looking at the companies in the ecosystem around, you mentioned work of Stanford faculty, but I think we're gonna see huge advances. And it gets into the way AI/ML is transforming our ability to detect small signals from a lot of noise. And I think we're still really at the very earliest stages. Back to Theranos, I'm glad you brought that up, and we should talk about that. But what... some have said that Theranos exemplifies the ills of Silicon Valley. Others have said that, as you describe, fraud is fraud, and that the jury clearly made that decision. To what extent do you think the hype around Theranos, and there for sure was a lot of hype around Theranos back in 2012-13? What was that a product of--of Silicon Valley? And what was it... just people looking to find something that was too good to be true?

Reed Jobs: No, of course it was about Silicon Valley. What are you, crazy? Of course it was. She is not the first CEO to sell herself and her charisma and story as an integral part of the pitch. I mean, that's happened. There's a long history of that happening before. It very well might happen again. I think the difference isn't that she was a huckster, I think the difference is, the stakes, when you're dealing in medicine, are not equivalent to when you're dealing in software. It's just very different. And it's one thing, if you're selling a software patch, or a fintech solution, but what she was doing was really dangerous. And the stakes are not equivalent. So I think it was actually there for everyone to see. I mean, you look at the board that she assembled, it was a bunch of foreign policy experts and ex Secretaries of State, not a single scientist there at all. So there wasn't really any true scientific oversight like you would have at normal biotech companies, and there's an interesting kind of adjustment that's happened in the Valley around how you look at biotech companies. I'd say, what Theranos exemplified, to me, is actually the big difference you see between software companies and biotech companies. And the big difference there is, in software companies, you have a Founder-CEO almost all the time. They're a crusader, and they're going to move mountains and deliver an incredible product. I know that phenotype very well. But it's actually very, very different in the life sciences. Because often, almost all the time, your founder is an academic, who may or may not want to leave their post. And if they do, it's actually oftentimes not the best candidate for the CEO position, because they are the best in the world at the science that they do, and therefore, you kind of want to extract the administrative overhead and let them do the science that they're the best at doing. So they can be incredible Chief Scientific Officers, Chief Medical Officers, but you kind of want to spare them from having to do a lot of the managerial overhead. And oftentimes, you recruit an external CEO to run the company. So she kind of had this software mold in the life sciences body, and that doesn't really work that much. And not only that, there just wasn't very much deep, scientific diligence that was done. I mean, obviously, like, Phyllis Gardner was a fantastic, early Cassandra here, saying that you got to look under the hood, because this is all a bunch of bullshit. And no one really did the work to do that. They kind of assumed, Oh, it's like a software company where we have a great founder and they'll just move mountains and figure all this out for us. And that's just not what the reality of working in the life sciences is like. And that's not really what the DNA of these companies are like.

Lloyd Minor: For sure. I think another lesson is to be honest with your customers and your people, right?

Reed Jobs: Of course, oh, yes, of course. Yeah.

Lloyd Minor: And we... you and I've talked about this before, but maybe you could describe it, but an earlier version of the iPhone had some problems with dropping calls, and--which phones back then were prone to do anyway, but an interesting discussion and session that your father had, saying, Look, it's dropping calls, and presenting the data, and also saying, We're going to get this right. We know it's a problem, we're going to fix it. And of course, Apple did. And now my iPhone doesn't drop calls very often. What lessons did you learn from that, and what can we all learn from that very historic and, I think, game-changing presentation that that your dad gave?

Reed Jobs: Well, so I guess you learned how to hold it right? No, well, in all seriousness, so I was lucky enough to be in some of those discussions. And it was an incredible learning opportunity, because it was just about being really honest with your customers. And treating them like adults. And realizing that there's a dialogue there and that's ultimately who you work for. You work for the customers. Be honest about what's wrong, and be honest about what you're doing to fix it. And if you're doing a good job, you should have nothing to hide, and people should be able to trust you that you're going to be able to pull off something that's in both of your best interest. And dad was always really good about that. Apple has continued to be great about that. I think the current leadership there is stellar and I just personally think they're wonderful people. So I think it's really actually quite simple, Lloyd. You just got to treat people like adults and be honest with them about where you are, what you know, what you don't know, and what you're trying to do.

Lloyd Minor: I agree. And I think the other message that I took away from that is humility. That you can be very successful, which your dad was, which you are, and at same time, when there's a problem, when there's a mistake, you acknowledge it, you own it, and you fix it. And that, to me, is what's essential about building trust. And some of that, I think, is getting eroded today. Not maybe in the proximate industries that we know, but across the board. I think a lot of that... the opportunity to be vulnerable, to have humility, I think, increasingly, that's being interpreted as weakness. And it really shouldn't be, in leadership. It ought to be seen as a essential feature of leadership, I would think.

Reed Jobs: Yeah, I agree. I don't think we're making any more mistakes than we used to, but I agree that I don't think we're being as honest about it as we used to. And I think honesty is one of the greatest signs of strength that there is. It's not weakness at all. It's actually trying to make some decisions that help people. And for people in power, for companies, that's really what their job needs to be. And it's a hard job. It's easier to try to obfuscate, or lie, or scapegoat. And it's a lot harder to be honest. But with people in power, we... are there because we expect the most out of them. And that doesn't mean that they're expected to be perfect, but that what is expected is that they're going to be honest.

Lloyd Minor: Absolutely. And maybe that's the critical message we all need to take away from the pandemic...

Reed Jobs: I hope so. I'm certainly ready to be taken away from the pandemic and move on into some sunlit uplands here. Oh my gosh, it's... yeah, it's going to be... you're going to see me in New Zealand and it's going to be amazing.

Lloyd Minor: That'll be fantastic. Reed, thanks a million. This has been really special.

Reed Jobs: Lloyd, so good to talk to you as always, and to see you in person here. It's a real treat.

Lloyd Minor: I agree.

Wrap-up

If you’ve got any thoughts, questions, or feedback, please drop me a line - I would love to chat! You can find me on twitter at @kevg1412 or my email at kevin@12mv2.com.

If you're a fan of business or technology in general, please check out some of my other projects!

Speedwell Research — Comprehensive research on great public companies including Copart, Constellation Software, Floor & Decor, Meta, RH, interesting new frameworks like the Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3), and much more.

Cloud Valley — Easy to read, in-depth biographies that explore the defining moments, investments, and life decisions of investing, business, and tech legends like Dan Loeb, Bob Iger, Steve Jurvetson, and Cyan Banister.

DJY Research — Comprehensive research on publicly-traded Asian companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Nintendo, Sea Limited (FREE SAMPLE), Coupang (FREE SAMPLE), and more.

Compilations — “A national treasure — for every country.”

Memos — A selection of some of my favorite investor memos.

Bookshelves — Your favorite investors’/operators’ favorite books.