Letter #201: Robert Wallace (2024)

CEO of Stanford Management Company | Three Pillars of Investment Success

Hi there! Welcome to A Letter a Day. If you want to know more about this newsletter, see "The Archive.” At a high level, you can expect to receive a memo/essay or speech/presentation transcript from an investor, founder, or entrepreneur (IFO) each edition. More here. If you find yourself interested in any of these IFOs and wanting to learn more, shoot me a DM or email and I’m happy to point you to more or similar resources.

If you like this piece, please consider tapping the ❤️ above or subscribing below! It helps me understand which types of letters you like best and helps me choose which ones to share in the future. Thank you!

Today’s letter is the transcript and slides of Robert Wallace’s presentation at the Norges Bank Investment Management annual investment conference. In this presentation, Robert walks through a framework that he uses when thinking about managing the Stanford endowment, a framework he calls “the three pillars of investment success:” strategy, execution, and governance. He ends the talk by sharing some of the Stanford endowment’s long term investment results.

Robert Wallace is the CEO of Stanford Management Company, which oversees Stanford University’s $35bn global, multi-asset class investment portfolio. Prior to joined Stanford, Robert was the CEO of Alta Advisors. He started his investing career at the Yale Investments Office where he worked under David Swensen and Dean Takahashi. Before becoming an investor, he danced professionally for 16 years as a leading dancer with American Ballet Theatre, the Boston Ballet, and the Washington Ballet.

I hope you enjoy this presentation as much as I did!

[Transcript and any errors are mine.]

Related Resources

Endowments

Transcript + Slides

Thank you very much for that very kind, too kind introduction, Trond. It's very nice to be with you today. And I'm going to share with you a framework that I often use it at Stanford University when I think about managing the Stanford endowment.

And it really focuses on three things that we have to do right, we have to do well, if we want to be successful the long run for Stanford. I call them the three pillars of investment success. They are strategy, execution, and governance.

So I'm going to talk about each one of those briefly, and then I'll finish with sharing some of our long term investment results with you.

But before I start, just to orient ourselves, maybe I'll mention a couple of high level facts about Stanford. So Stanford University is a research university located in Palo Alto, California, about one hour south of San Francisco, in the middle of what's sometimes referred to as Silicon Valley. In fact, the technology ecosystem that is Silicon Valley really built itself around Stanford over the last 50 or 60 years, and important companies like Google were actually started on the Stanford campus. The university was founded in the late 1800s, and unusually at the time, it was founded as a co educational school. So the very first class that matriculated at Stanford had both men and women in it. Today, there's 7000 undergraduates at Stanford, 10,000 graduate students, and 2300 faculty members. The endowment, as Trond just mentioned, is about $40bn. And this year, it will distribute, to the operating budget of the university, $2bn. So that is the single largest line item in Stanford's $9bn operating budget.

So that brings me to the first thing that you need to do right if you want to be a successful long term investor. And that's strategy. And here's a quote from the great Norwegian polar explorer, Ahmanson: "Victory awaits him who has everything in order, people call it luck." What a nice succinct way to talk about strategy. You have a goal, you need to build a plan, a strategy, to achieve your goal.

We have two key goals for the Stanford endowment. One, we want to be able to be a material part of the of the life, the academic life, of the current generation of students and scholars at Stanford. So I mentioned roughly $2bn flowing from the endowment this year, that's about 5% of the value of the endowment. That's goal number one. Goal number two is we want to be at least as impactful and supportive for all future generations of students and scholars at Stanford. So that introduces a concept that we call the preservation of purchasing power. So that just means that if you're spending 5% every year from your endowment, you have to earn back at least that 5%, but you also have to earn enough to offset the impacts of inflation. The inflation that we care about at Stanford is higher education price inflation, which tends to run a little bit higher than consumer price inflation. So if CPI runs at 2-3% over 40 or 50 years, higher education price inflation is going to run at 3-4%. So when you put 5% payout together with 4% inflation, you have a pretty high--you need to have a pretty high expected return to offset your spending and still preserve the purchasing power of the endowment.

So the way that we do that is we have an equity bias in the portfolio--equities have a higher expected return than fixed income or cash, and that's really important in the long run if you want to achieve that second goal. Unfortunately, as we all know, equities are very risky. You rank the lowest priority in the capital structure, it's much more possible to lose your capital and have a capital impairment. Equities are also very price volatile. Volatility is not the only risk that you care about, it's not even--maybe not even the main risk. But it is a risk. And the reason that it is a risk is because unnecessary or extra volatility that you're not being paid for will erode your long term compound return. So to make this clear with a simple example, if you start with $100 and you have a 50% return in year one and a negative 50% return in year two, where do you end up? Well, at the end of year one, your $100 has become 150. And then in year two, you lose 50%, it becomes 75. So you're up 50, down 50, but you've just lost 25% of your money. So volatility erodes long term compound returns. You can see that with the identity shown on the bottom of the slide. Whenever volatility is greater than zero, your geometric, or your compound return, will be lower than your single period expected arithmetic return.

So how do we deal with that extra risk? We diversify. We look for something that Nobel laureate Harry Markowitz called the free lunch. So we own different types of equities. We own some equities in the United States, some equities in Europe, some equities in Asia, some that are purely corporate, so think of venture capital, some that are backed by physical assets, so think of real estate. And when we put those equities together, they are positively correlated with each other, but they're not perfectly correlated. So they react somewhat differently to different macroeconomic states of the world. So we starting to gain some stability through that diversification. Then we introduced two other asset classes: fixed income and absolute return, which is a carefully chosen relative value strategies from the hedge fund world, and we put them together with the equity asset classes in our portfolio, we end up with a portfolio designed to give us a pretty high expected return, but with low levels of volatility or reasonable levels of volatility.

This is our policy asset allocation at Stanford right now. So this is the the most succinct way that I can explain our strategy. Down the left hand side, you can see all the major asset classes as we define them. On the right you can see their policy target weights. And everything on this slide is an equity oriented asset class except for those two middle asset classes: absolute return and fixed income. If you do the quick math, you can see that the equity asset classes add up to about 70% of the portfolio. So here you can see, we're designing a strategy to achieve our goals. This is an equity oriented portfolio, yet it has substantial levels of diversification.

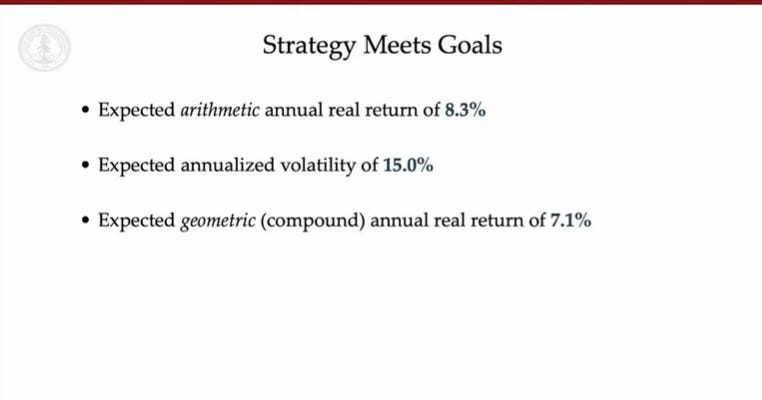

When we model this portfolio, it gives us an expected single period return of 8.3%. So that's deflated by higher education price inflation, expected volatility of 15% on an annual basis, and that leads to a compound return expectation of 7.1% net of inflation. So if this is true, if we designed a--if we specified the portfolio correctly, and we achieve a 7% real return, we can pay out 5% a year, even a little bit more, and still preserve the purchasing power of the endowment for future generations.

The next key pillar that we have to get right is execution. And this is one of my favorite quotes from the American inventor, Thomas Edison. "Opportunity is missed by most people, because it becomes it comes dressed in overalls, and looks like work." And this really is what we do most days at Stanford Management Company. We execute against the strategy that I just showed you. So execution has a couple parts.

The first is portfolio management. So every day we get a flash estimate of where the portfolio is, it comes out about 7:30am. And we may start to make one of two types of actions. The first is we may rebalance the portfolio between asset classes. So as market movements take those asset classes away from their policy weights, the risk return and liquidity characteristics of the portfolio start to shift from what we think is ideal. So we will normally sell what's gone up in value and bring it back down to target, and we'll buy what's gone down in value and bring it back up to target. And that way we preserve the right risk return for the portfolio going forward. So that's rebalancing. Sometimes we rebalance once a week or once every two weeks. In volatile capital market environments, we may rebalance every day.

The second type of portfolio management that we conduct is rotating capital inside of asset classes. So I should take a moment and explain that the security level decisions for the Stanford endowment are made by external partners that we find, we identify, we try to build long term relationships. These are very specialist partners, very, very good at what they do, whether it's stock picking or venture capital or private real estate. It's very hard to find these partners, and we'll talk about that in a minute. But once we have found them, we have a strong, trustful communication. And when their opportunity set evolves, we can take some action to optimize Stanford's capital. So if there are opportunities that get more attractive, we can give them more money. If it gets a little bit less attractive, we can take some money back. So we're always doing that. The combination of rebalancing between asset classes and rotating capital within an asset class can sometimes take up 30, 40, or even 50% of the value of the endowment in a single year. So we're very active in managing the portfolio.

So I mentioned external partners--this is a really critical part of execution, and a huge part of what we spend time on at Stanford Management Company. These are, generally speaking, pretty small, niche boutique investment firms that we find--they're very principally oriented. You probably wouldn't know the names of most of them. And I'll tell you what we look for when we when we when we when we go looking for new partners.

First of all, we want to see discipline, we want to see partners that understand the difference between investment and speculation. Understand that some things can be analyzed with a high degree of rigor, and some things can't be. And we want them to focus their investment work on the former and not the latter.

We want them to have a strong, thorough, and repeatable process. Something that we can see and feel and touch that surfaces all the hard and soft variables that they need to think about in any given situation.

And then finally, we want them to take all that data and apply superior investment judgment. That's the hardest part for us to suss out when we're meeting with a new partner. Really, how do they assess risk and return? What kind of weights do they put on the various parts of their investment thesis? And usually, when we make a mistake about a partner, it's usually that we get their investment judgment wrong.

We like it when our partners have the appropriate amount of capital. So investment success often leads people to have too much capital. They kind of outgrow their competitive sweet spot. It's very common. We'd like it when that happens that our partners return capital to us. And so it's really important that size doesn't become the enemy of performance in our portfolio.

And finally, we try to structure a strong economic alignment of interest with our partners. So are we compensating them appropriately over the right time horizon, over the right cost of capital? Are they putting their money alongside us so that we're eating the same cooking? Do they do well when they do well for Stanford? These are all important parts of what makes a successful long term relationship. I should also mention at Stanford that we believe long term investment success requires an appropriate regard for human and environmental welfare. So we insist that our partners have that same philosophy, that philosophical alignment of interest is just as important as the economic.

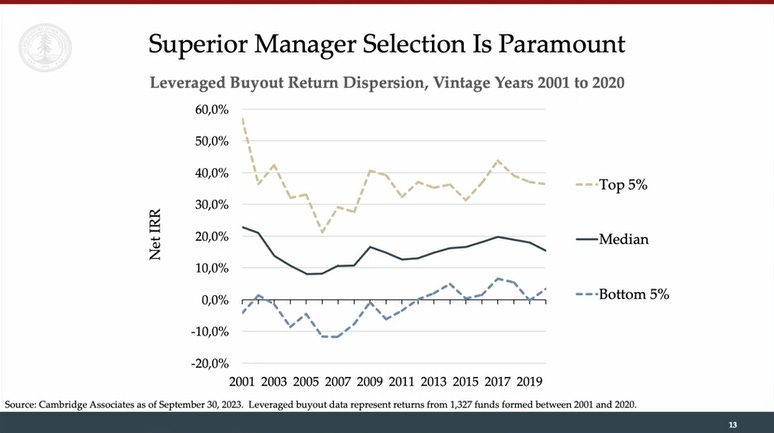

This slide sort of gives you some data on why partner selection or security selection is so important. We're looking at leveraged buyout funds from the United States formed between 2001 and 2020. So these are reasonably mature buyout funds. The top dotted line is the top fifth percentile buyout result for that year, the bottom line is the bottom fifth percentile, and the median is shown in the solid line in the middle. So one thing immediately jumps out from the slide--if you're in the top of the distribution, if you're in the top fifth percentile of the leveraged buyout universe in the United States, you're outperforming the median by around 20 points per year. These are net annual IRRs, so 20 points per year on a closed end fund that's 10 or 12 years in life is a lot of money at the end of the day. So that's an incredible outcome, if you can be in the top of this distribution.

The second thing that jumps off the slide is--look at how bad you do if you're in the bottom of the distribution. If you're the bottom fifth percentile, you're underperforming the median by 20 points per year. You're almost certainly ending up with a result that's below the public markets that you could access very easily for low cost. So this slide really is why execution is so important. If you have a complex strategy, like Stanford, you have to feel certain that you can be at the top of the distribution in this type of asset class, I could show you similar slides for venture capital--it would be even more dramatic--private real estate, absolute return strategies. All of them show this type of dispersion, which means that you really need to execute well if you have the type of strategy that Stanford has.

How do you execute well? Well, you have to have the right team. So we hire people that are very intellectually curious. We heard about this from some of the early speakers. People that really want to continually grow as investors that seek and accept a high degree of personal accountability for their work. So I often tell our analysts at Stanford Management Company, You are the Stanford Endowment. I really want them to internalize their work for Stanford. It helps that they're motivated by Stanford's academic mission. This is--it's hard work. And so having some psychological benefit knowing that you're doing something that is very valuable for the world is really important for the team.

We also try to grow our own talent. So we're often hiring right out of Stanford undergraduate and training our own training our own investment professionals. In fact, I'm joined today by my colleague, Thea Rosenberg, who's an analyst in our office. Thea was born and raised in Oslo. She went to Stanford undergraduate, and while she was an undergraduate there, she took our class in economics that we teach once a year, and she became an intern in our office. After she got her master's degree, she joined us full time. And so Thea's a great example of someone who's intellectually curious, seeks and accepts a high degree of personal accountability, and is very motivated by Stanford's mission. We're delighted to have her on the team.

You take the right people, and you put them in the right culture. So we have a very open, collaborative culture. I like to think we're all in the same rowboat pulling towards the same shore. We all sit on the same open floor plan, we try to reduce bureaucracy, we try to minimize hierarchy. That's a lot better for communication, it's a lot better for training your junior professionals, and it's also a lot more fun--and having fun is a really important part of long term success.

So the final pillar of investment success is governance. And this one is talked about less, but it's just as important. Here's a great quote from another incredibly impressive Norwegian polar explorer, Nansen: “The difficult is what takes a little time, the impossible is what takes a little longer.” And this is a great quote about governance.

So governance--just as important as the other two pillars--and good governance supports the disciplined execution of the right strategy. And this is really critically important, particularly in times of market extremes. So you can think of a time of extreme euphoria where there's some hot sector, some hot asset class of the day that's dramatically outperforming everything else. And by definition, your diversified portfolio will underperform that hot sector. And bad governance would would say, Chase that sector. Always go with--try to catch up with what's performing well. That's unlikely to work out well over time, and certainly would entail taking a lot of risk. The other type of extreme is fear and panic. So think of the Fall of 2008, when everybody was selling every risky asset and trying to raise cash. The right thing to do in that environment, if you were an institutional investor, was to buy the things that people were selling, buy the things that had fallen 40%, 50%, 60%, and sell the other stuff, to rebalance your portfolio, to bring the desired risk and return back to the portfolio on a go forward basis. So governance reinforces the disciplined execution of the right strategy, and shelters the management team from external influences that might make that very hard.

Okay, so, just to finish on this one. This is our long term investment results. So if you had taken--so Stanford Management Company was formed in 1991 to professionally manage the endowment. If you had taken $100 in 1991 and invested it in the endowment portfolio, you would have made 32x your money by the middle of last year. That's roughly double the result that you would have achieved in a typical US endowment fund and roughly 4x the result that you would have achieved had you taken that same $100 and invested it in a 70/30 portfolio--70% global equities, 30% high quality bonds. So if you form the right strategy, if you specify the right strategy based on the goals that matter to you, if you have the ability to execute on that strategy, and then you have good governance that protects you from outside interference, you can get attractive long term investment results. Thank you very much.

If you got this far and you liked this piece, please consider tapping the ❤️ above or sharing this letter! It helps me understand which types of letters you like best and helps me choose which ones to share in the future. Thank you!

Wrap-up

If you’ve got any thoughts, questions, or feedback, please drop me a line - I would love to chat! You can find me on twitter at @kevg1412 or my email at kevin@12mv2.com.

If you're a fan of business or technology in general, please check out some of my other projects!

Speedwell Research — Comprehensive research on great public companies including Constellation Software, Floor & Decor, Meta, RH, interesting new frameworks like the Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3), and much more.

Cloud Valley — Easy to read, in-depth biographies that explore the defining moments, investments, and life decisions of investing, business, and tech legends like Dan Loeb, Bob Iger, Steve Jurvetson, and Cyan Banister.

DJY Research — Comprehensive research on publicly-traded Asian companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Nintendo, Sea Limited (FREE SAMPLE), Coupang (FREE SAMPLE), and more.

Compilations — “A national treasure — for every country.”

Memos — A selection of some of my favorite investor memos.

Bookshelves — Your favorite investors’/operators’ favorite books.

Excellent outline of the process of wealth management.