Letter #232: Jawed Karim (2006)

Cofounder of YouTube and YVentures | YouTube: From Concept to Hyper Growth

Earlier this week, Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai revealed that YouTube LTM revenues had surpassed $50bn for the first time.

YouTube Timeline:

Feb. 2005: Jawed Karim emails Steve Chen & Chad Hurley about a “Video H or N.”

Oct. 2006: Google announces they are acquiring YouTube for $1.65bn.

Oct. 2024: Google announces YouTube has surpassed $50bn in LTM revenues.

YouTube went from idea to $1.65bn acquisition in 18 months, and from pre-revenue to $50bn revenue in 18 years. YouTube negotiated their $1.65bn acquisition over just one week, and today they generate $1.65bn in just over one week.

Fun Fact: After YouTube was acquired, Taiwanese-American cofounder Steve Chen revealed that all of their acquisition discussions were held in a Denny’s in Redwood City. Just 13 years earlier, in a Denny’s across town in Berryessa, another Taiwanese-American founder, Jensen Huang, cofounded Nvidia.

Two weeks after Google announced it was acquiring YouTube, YouTube cofounder Jawed Karim gave a talk at UIUC sharing YouTube journey from pre-inception to acquisition, aptly titled YouTube: From Concept to Hypergrowth.

In this talk, Jawed shares the process of how YouTube the product came to be, because when he sees an interesting product, the first thing he thinks about is how they came up with the idea, how they built it, what troubles they ran into building it, and why such a product hadn’t been built earlier. He starts by sharing his favorite video, then some high level stats for the platform. Next, he discusses the concept of a killer application, before breaking down several examples products that influenced/developed the base that made YouTube possible (LiveJournal, HotOrNot, Wikipedia, Friendster, del.iocio.us, Flickr). In the next section of his presentation, Jawed gives the students context on the state of the video sharing market before YouTube, then shares why the timing was right for a product like YouTube to come into existence. After sharing YouTube’s product journey, Jawed moves on to discuss its business journey, from ideation to prototype to first launch to marketing to revamp to initial traction to hypergrowth. He ends the talk by answering, or rather asking, What’s next??

Jawed Karim is a Cofounder of YVentures (fka Youniversity Ventures), which was formed by Jawed, Kevin Hartz, and Keith Rabois, and an early investor in companies such as Airbnb, Palantir, and Reddit. Before founding YVentures, he cofounded YouTube with Steve Chen and Chad Hurley, two of his colleagues from PayPal, where he was a Software Architect helping develop real-time antifraud systems. He joined PayPal while it was still called Confinity (and while he was still in college), and stayed through the IPO and eBay acquisition. Jawed started his career as an intern at Silicon Graphics, where he served as a data engineer on the Visible Human Project.

I hope you enjoy this presentation as much as I did!

[Transcript and any errors are mine.]

Related Resources

YouTube

PayPal

Anthology

Compilations

Elon Musk (512 pages)

Peter Thiel (536 pages)

Letters

Transcript

Yeah, thank you very much for that introduction. And I also want to thank the people who put together this event every year. And I know when I was an undergrad here, which was actually not that long ago, back in 2000, is when I left, I would always go to these types of events. And certainly the ACM conference and also the other distinguished speaker lecture series. And I thought I always got a lot out of those talks. Because it was really interesting to sort of see what other people had to say, coming from industry and academia. And so hopefully, you'll learn something new today as well.

So, when I was putting together this talk, I decided that I'm not actually going to talk all that much about YouTube as it is currently, because I assume that everyone has seen YouTube and uses it.

So what I'm going to talk more about today is sort of more the process of how the product came to be. Because when I see an interesting product that's very successful, my first question is Well, how how did they come up with that--first of all? How did they come up with that idea? Did someone just wake up one morning and say, Hey, we should do this? And what kind of troubles did they run into? How did they overcome those? And why is it that this idea is so successful now? Why didn't it happen earlier? And so I'm hoping to be able to clarify that for you.

So the first thing I'm going to do is I'm going to show you one of the first videos that was uploaded to YouTube--and it's actually still my favorite video. And I think it illustrates really well what what YouTube is all about.

Right. So why did I select that video? It's because this video really shows what YouTube was all about, which is, if you have a good idea, and if you just go out there and you make a video, you can get an audience of millions, almost instantly, for free.

And that's what this guy did--Matt Harding. And I've actually met him. And this video just took off. And YouTube was--there's this platform called YouTube, and he was able to deliver his video to millions of people for free. And that was never possible previously.

So what I'm going to do first is talk about what YouTube has achieved, and then I'll tell you how we got there.

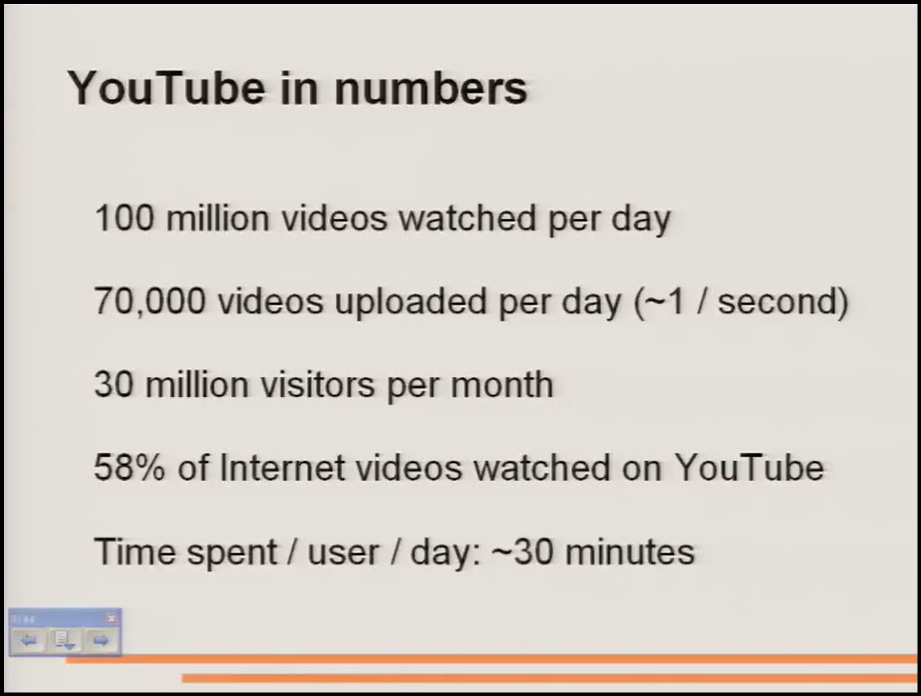

*Note: I usually refrain from inserting commentary into these letters, but I thought it would be worthwhile to share updated figures (estimates) for these KPIs.

These stats in 2024 (unofficial):

Videos watched per day: ~5bn

Videos uploaded per day: ~3.7mn (~50 / second)

Visitors per month (MAU): ~2.5bn

Percent of Internet videos watched on YouTube: ~60-70%

Time spent / user / day (US / Global): ~48 minutes / ~19 minutes

So we're streaming over 100mn videos per day. Currently. There are 70,000 videos uploaded every day, which is almost one per second. And we receive well over 30mn visitors per month. And this statistic I find the most impressive: we serve 58% of videos shown on the internet. I mean, even to me, that's just unbelievable. And this one's also very interesting. The average user spends about 30 minutes per day on YouTube, which is a significant number because that's more than a sitcom.

So actually, I'm just curious: how many of you use YouTube every day?

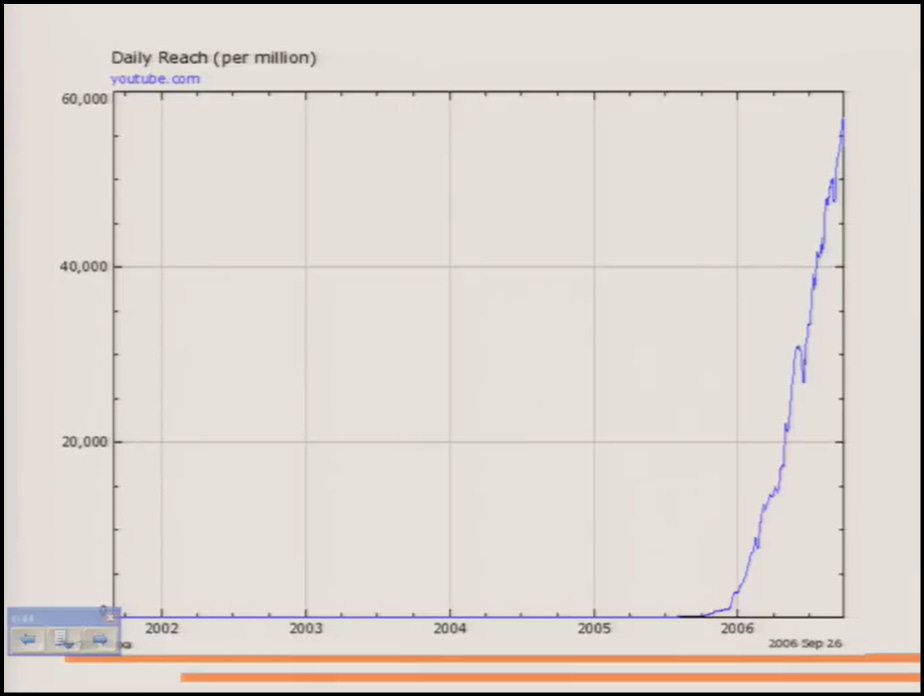

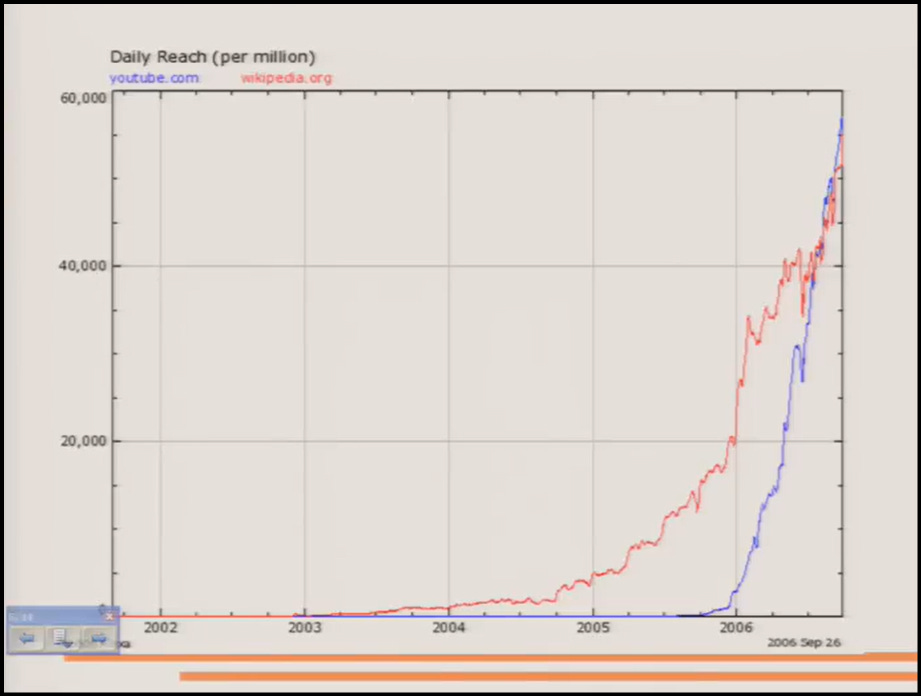

Okay. So let's look at the growth of YouTube, which is unprecedented--in many ways.

So not many people will dispute the statement that YouTube is the fastest growing website in internet history. So looking at this graph, it looks very impressive.

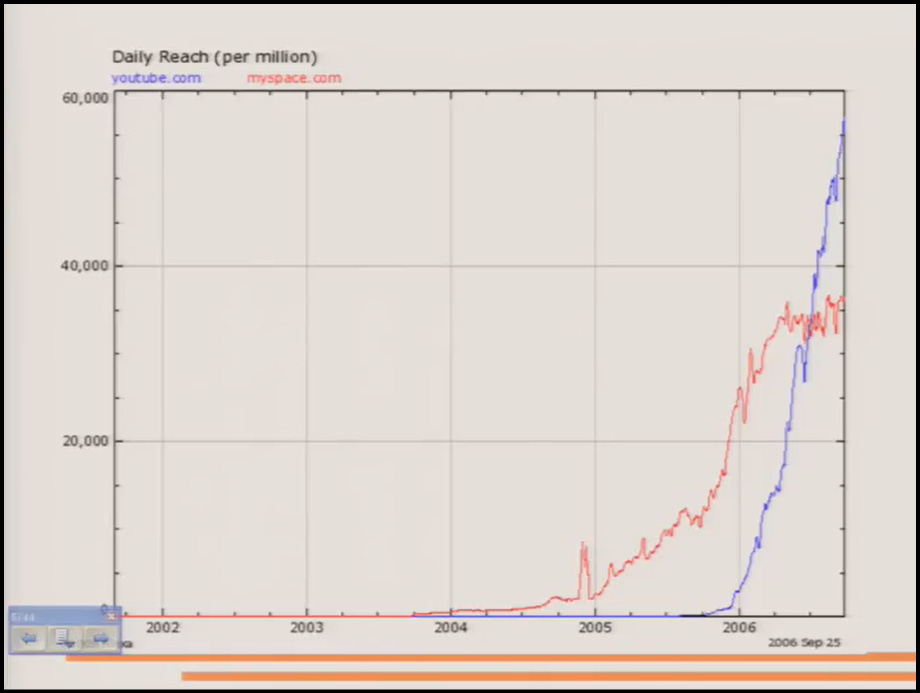

But let's compare it to a few other websites to get some reference.

So this is compared to MySpace.

And MySpace actually launched in, I think, 2003. And it has been called one of the fastest growing websites in internet history. And YouTube just launched last year, actually.

And Wikipedia is actually one of my favorite websites that I've been tracking very closely from the beginning.

And it looks like we've even caught up with Wikipedia. Wikipedia started in 2001.

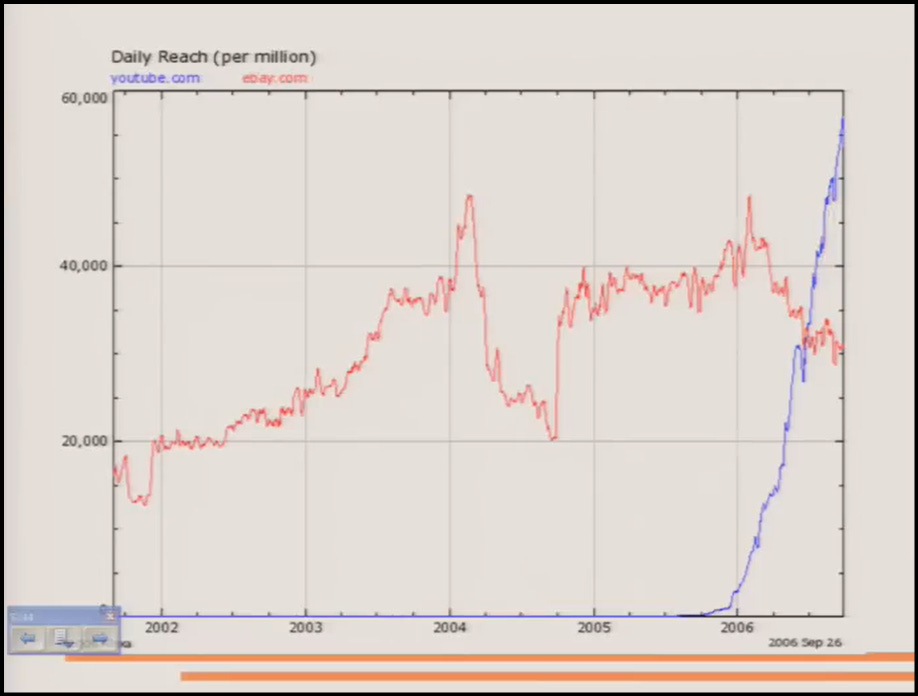

And it's also useful to compare YouTube with old timers like eBay, which have been around since 1995.

So we've eclipsed eBay as well.

So what I want to talk about today is this concept of a killer application. How many people have heard of this phrase before?

Okay, so it's essentially just an application that proves the usefulness of the underlying technology. And I think the first killer app--most people will agree, is this spreadsheet program that came out when PCs first became popular.

And the interesting thing about these killer applications on the internet is that, well, first of all, there seems to be a new one, or several new ones, every year, which is pretty incredible. The other interesting thing is that they seem to almost build on top of each other. So you will get one killer app that will establish the base for the next killer app to come along.

And in sort of coming up with the idea for YouTube, I think it's really useful to to look back and see exactly how those innovations progressed.

So I've selected a small number of killer applications.

And this is not supposed to be the list of the most successful websites ever, but it is a list of killer apps in the social content space, which I think, together, these kind of developed the the base for YouTube--for a product like YouTube to become possible. And what's also interesting about this list is that anyone in this room could probably implement any of these websites in a pretty short period of time. I mean, even an undergrad in CS could easily, I think, implement most of these in perhaps a few weeks. Of course, scaling them would be an entirely different problem. But it is kind of encouraging to know that the initial implementation is not that complicated.

So the first one is Live Journal.

And actually, I've had varied responses on this. How many people have actually used Live Journal?

So this was, back in 99, this was the first time that everyone could easily publish their personal content. And back then, that was actually a fairly novel thing. Before that, blogs didn't really exist before that, but if people wanted to have their own blogs, they had to write their own software or they had to update HTML files every day. And back then, most people weren't really familiar with that technology. So Live Journal, the contribution that Live Journal made was that it enabled anyone to broadcast personalized content on the internet.

And of course, there was social interaction on the internet prior to that on, for example, IRC or newsgroups. But that was more for like, nerds, whereas this really included everyone. And what was also interesting about this is that it showed for the first time, I think, that people were really willing to share really personal details about themselves on the internet. If you look at these blogs today, people are sharing everything from what they're eating, who they're dating, or whatever. And I think before this came along, it wasn't clear that people really actually were interested in sharing that information.

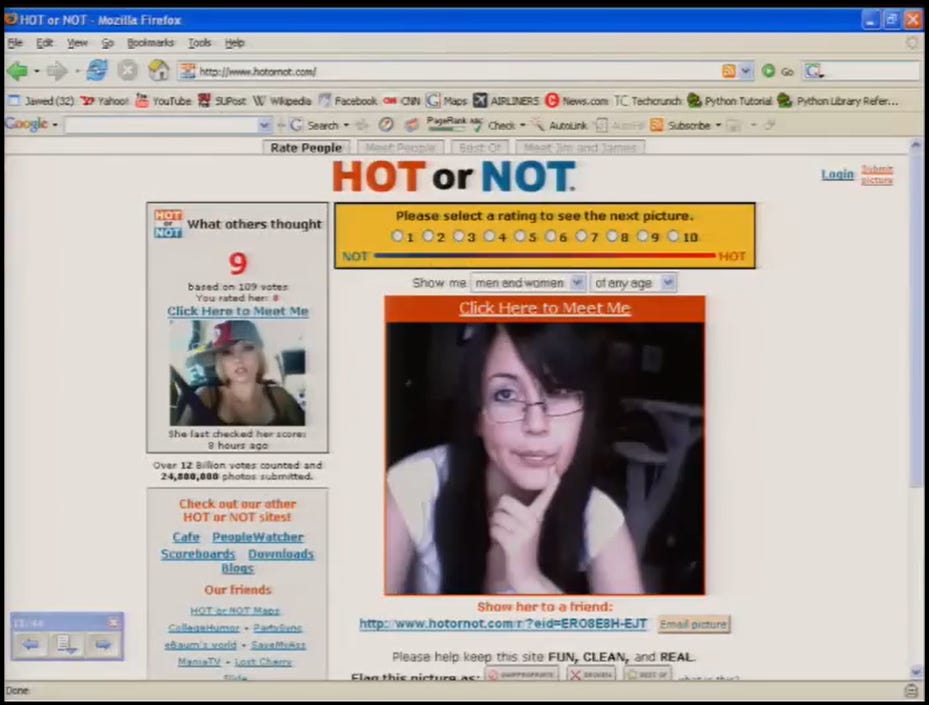

Next website that I think made a major contribution is HotOrNot.

And it's a really silly concept. You can upload your photo, and anyone can view your photo, and you can rate everyone's photo.

How many people here have used this?

So, HotOrNot launched in 2000. And it really--it took off like a rocket. I was incredibly impressed. And I remember looking at this website, and it's just--it's so impressive that two people could just build this website and it just instantly took off and became a huge hit.

And HotOrNot made a number of key contributions.

One was: this was really the first time that someone had built a website where anyone could upload content and anyone could download that content. That was, at the time, before HotOrNot came out, that was really considered kind of a crazy idea. And it wasn't clear if it could work. It wasn't clear if it could scale. Just from the bandwidth and software demands. It also wasn't clear if it could even be profitable. HotOrNot was--or I think is--profitable. And that was especially impressive, back in 2000, because that was before the time of Google AdSense, for example. And so back then you actually had to find advertisers yourself--it was a lot of work. Whereas these days, you can just paste in some some Google HTML code and it'll do it for you.

The other interesting thing about HotOrNot is that it really pushed digital camera usage into the mainstream, because when HotOrNot first launched, I remember looking at the site, and you could sort of tell that most of the photos were scanned. And I think if I show you a photo online, usually you can sort of tell whether it was scanned. But as time went on, that year in 2000, you could really tell that more and more photos were being taken with digital cameras. So I think that was a major factor in popularizing digital cameras.

The next killer app that made a major contribution is Wikipedia.

And Wikipedia is--I went to a talk by the founder of Wikipedia, Jimbo Wales. And he said very clearly that Wikipedia is not really about technology. There's are no huge technological surprises in Wikipedia. If you look at the implementation, of course, it's very impressive, the degree to which they have been able to scale. And there's a lot of hardware involved and stuff, but really, he said, Wikipedia is mostly a social experiment, because it answered a number of questions.

One was: Are people really willing to put in their own time to create this entity? No one on Wikipedia is paid. They do this for fun. And the second question is: Can millions of people really collaborate and make millions of tiny little edits where the end result is a cohesive article? Like an encyclopedic article? That wasn't really clear, and Wikipedia really answered those questions.

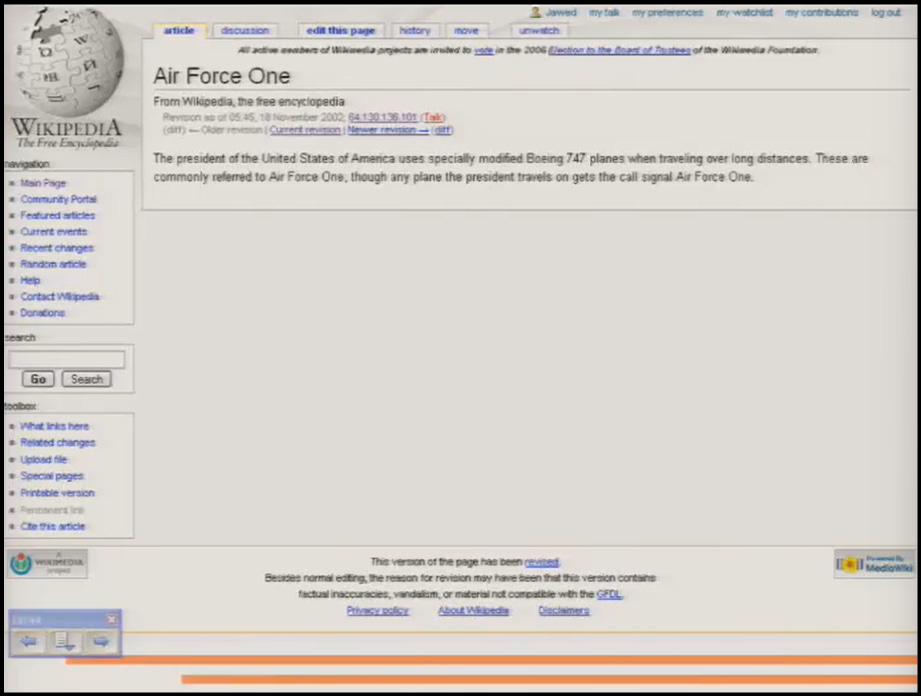

And I remember looking at Wikipedia in November of 2002--and I was just sort of sitting around and just bored out of my mind, and I went to Wikipedia and typed in Air Force One. And there was no article on Air Force One. And I looked at the Help section, and I saw sort of how this was supposed to work, but I was really skeptical. I didn't think that all these people could really collaborate to create any sort of article. So I started a simple experiment, and I simply started this article. And I just said, the President of the United States of America uses specially modified Boeing 747 planes when traveling over long distances, and so on. So I just added two sentences, and I wanted to see what would happen.

And if you look at it, today, it looks like this.

And that's a very cohesive article. Like many on Wikipedia, it's very interesting. There's all sorts of facts and photos and links to other Wikipedia articles. So when I saw this, it really impressed me because it sort of demonstrated what you can do with a community website and how much potential there is for people collaborating to create something bigger.

And so of course, everyone knows Friendster, which came out in 2002.

And it wasn't actually the first social network. There was one prior to that called sixdegrees.com, but it relied more on email addresses and it wasn't as easy to use. And I think it just didn't work because if you've lost touch with someone, you're not going to know the email address, so it's kind of hard to add them as a friend. So it was really just a matter of the right product coming along at the right time. And what Friendster did is they really commoditized social networking. So ever since Friendster, pretty much any community website that's out there is going to have the social networking component. And all those social networks--the social networking part really hasn't changed much. It's still pretty much the same.

So Delicious, I think, is a slightly more obscure website.

Although it's become very popular recently--how many people have used Delicious?

So the idea is very simple. I think the initial idea was, Well, what if you could store your bookmarks remotely so that when you're using different computers you can still access the same list of bookmarks? So then they went one step further, and they said, Well, if all these people are storing their bookmarks on the same server, we could see--for example, if I have one bookmark that I find interesting, and someone else has the same bookmark stored, then chances are some of the other bookmarks that other person has are also interesting to me.

That was a pretty simple idea, but Delicious really popularized this concept of tagging. So tagging just means when you upload a piece of content, you add some tags to it, or keywords that are relevant to that content. And the surprising thing about tagging is that it's trivial. I mean, it's trivial to implement. But it works surprisingly well. And it works on any sort of information, whether it's text, images, or videos.

And it's really interesting that sometimes the simplest solution ends up being one of the best solutions. For example, people have been working on image recognition and all this stuff, which, although they're making progress, it's really not to the point where it can be used by everyone. And so it's kind of cool to see that.

And, of course, as you know, tagging is now used in any site where people upload content, such as Flickr.

Flickr is essentially just HotOrNot plus Delicious, in some ways. I mean, they just took photo sharing and opened it up a little bit more. At the time when Flickr came out, photo sharing was actually kind of old news. Yahoo photo albums had been around for a while--but the difference was that a lot of the other photo sharing services, they're closed off systems. So you could have your own album that your family could see, but certainly they weren't cross referencing between albums and you couldn't search all across the database--well, first of all, because they there was no concept of tagging.

And Flickr, like Delicious, was actually acquired by Yahoo. And I think both are continuing to grow very quickly. And finally, the thing that all these killer apps have in common is they all prove that you can use this platform of Python, PHP, MySQL, and Apache to build these services--and it works out really well.

And so this is just if you search for Air Force One on Flickr, you get to see what photos everyone has uploaded.

But of course, we're talking about video. So when you have an idea--when you have a product that makes something easier to do, one question to ask is, Well, what did things look like before that product came along?

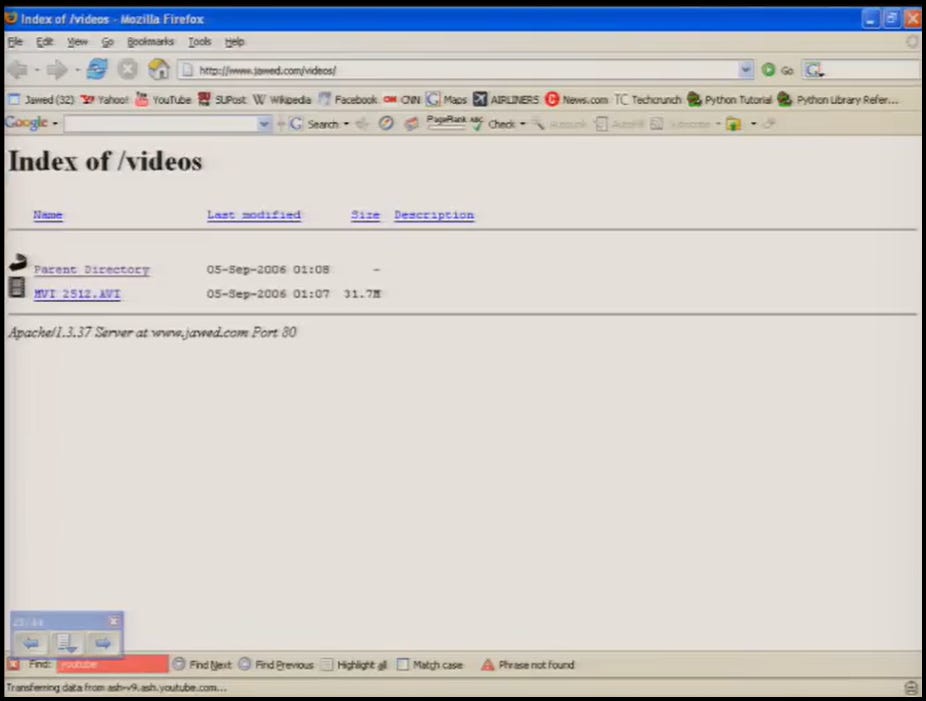

So one good question to ask is, Well, in 2004, which is, by Internet standards, ancient, ancient history, what did things look like before YouTube? How did people share videos? What was the best way to share videos?

And it looks pretty much like this.

Back then, if you wanted to share a video with someone--and I remember doing this--is you would basically upload it to your website, if you had a website, you would tell people, Go to this URL, and right click on the file, select Save As, wait for it to download, and then once it's downloaded, double click on it. And hopefully, you'll have the right video player installed. Even if you had Windows Media Player, it wasn't clear that you actually had the right codec installed.

So for example, if I had decided to encode this file with a DivX codec, which is very popular, to save space, the viewer would have had to download DivX, which would either cost $25, if they were to download the commercial version, or they could use the open-source, reverse-engineered version, which is called Xvid. But Xvid, you can get the source code, but because of patent issues, the binary isn't actually hosted anywhere. So you might actually have to compile your own codec. So unless you're a CS PhD, that was probably not going to happen.

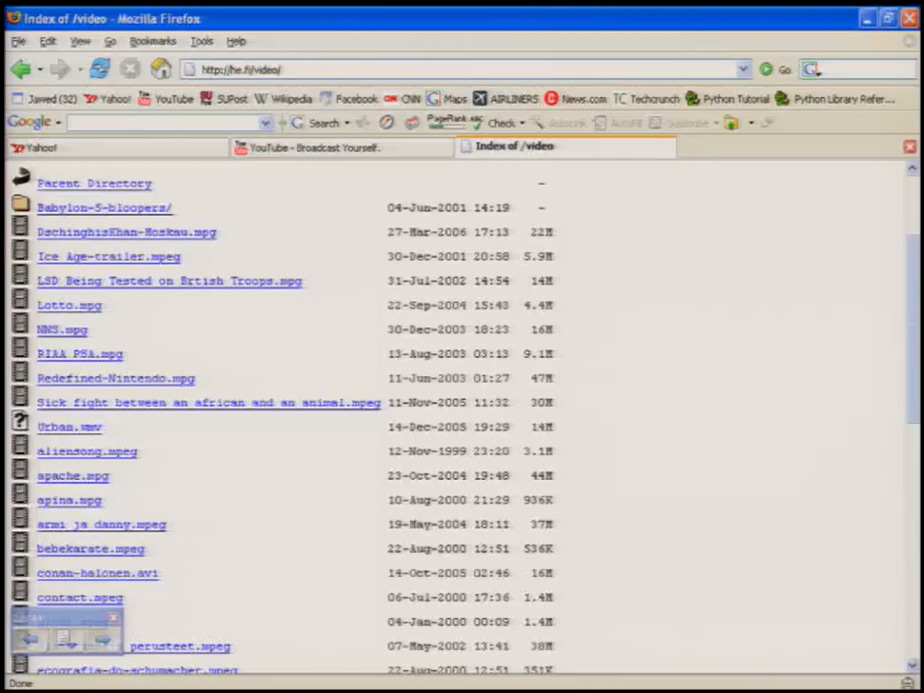

So video sharing was definitely very difficult at the time. The other thing to ask is, Well, what was the best way people could find videos, or browse videos, before services like YouTube came along?

And this is what it looked like.

What you would basically do to find a video is you'd go on Google, type in what you're looking for, and just hope that you would find someone's directory with a bunch of files.

So this is obviously bad in several ways.

First of all, the only information that you're going on is the file name. So that may not be very helpful. For example, while LSDbeingtestedonBritishtroops.MPEG is fairly descriptive, but Apache.MPEG could be just about anything. It could be a video about Native Americans, or web servers, or about helicopters--it's totally unclear.

And also, with this approach, there's really no connection between the videos. For example, if you find one great video about, I don't know, 747s, then, well, you still haven't found anything else. You'll still have to repeat the search to find other similar videos.

And this also doesn't connect the users at all. For example, if there are a lot of people who are huge fans of watching videos of troops on LSD or whatever, they won't be able to collaborate, because they won't even know that other people are looking at this. So there was no interaction between the owners or the viewers of the videos.

And then, the other thing to look at is, Well, what did the video viewing experience look like in 2004?

And there were pretty much two options: there was Windows Media Player, and Real Player.

And so we've all had this experience with Windows Media Player. Click on a file and it starts buffering. Buffer some more, and some more. And it'll say, Oh, I have the wrong codec. I don't have the codec that this file was encoded with. So would you like to download it? So you download the codec, and it's buffering, downloading. And then it'll say, Oh, well, actually, codec doesn't work, but I can play the audio for you. So wasn't really that ideal.

And the other option then was Real Player. But as most of you probably know, the big problem with Real Player is that it takes over your system. Now, I remember installing it, and it wants to be your jukebox, and wants to be your toaster, and wants to do everything on your computer. And it was even difficult to find the free version. They would have this Real Player 2.0 or whatever that you had to pay for. If you wanted to find the free one, there would be this tiny link on the real page that you had to find. It was just a mess.

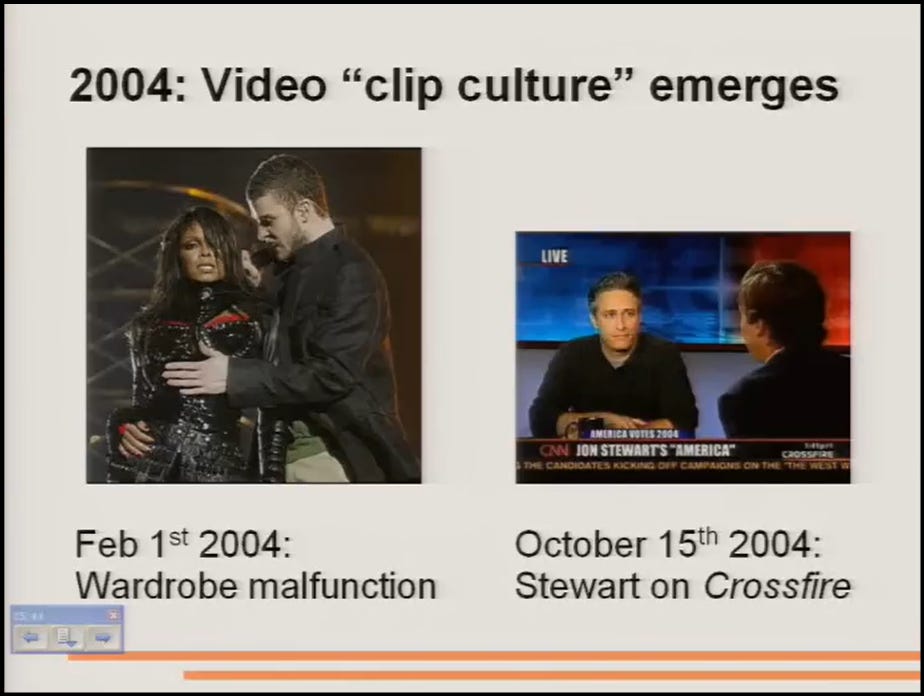

And what happened around this time, in 2004, is that I think this was the first time that this sort of clip culture emerged on the internet.

So, the clip culture that we see now is basically this demand that you can find any video at any time, and you can share it with other people, or you can show it, you can share your own videos with other people. And it's sort of this instant gratification ability to do what you want to do.

And there were a couple of events in 2004 that kind of fueled this desire to be able to do these things.

One was this (Janet Jackson). So this, of course, happened on television, but it only happened once and never again. And so for anyone who wanted to see it after that, well, they had to find it online.

The other big event that I remember was this interview (John Stewart). And this was, also of course, shown on television once, and not after that. And so people who missed it, they--everyone was talking about it, but people who missed it, they really wanted to be in on the joke, so they would try to find it online. And when they did, they were running into these problems that I was describing.

So I think it was very clear at this time that there was this demand for a better solution.

And it was in December 2004 when I was reading this article in Wired magazine called The BitTorrent Effect.

And it's actually an article about BitTorrent. But what the editors of this article did is, they really identified this sort of video, this need for a video solution that needed to emerge, that people wanted to use. And they talked about it because BitTorrent, of course, is used mostly for very large files--most of them being video files.

And they noted that the Crossfire (John Stewart clip), the audience of that clip, was fairly large on television, but it was three times larger online. And this--when I read this, it really sort of hit me that, Wow, now, to get the biggest audience, maybe online is the way to go, and not television.

And they also, I think, did a really good job in this article of identifying this clip culture. They said that the concept of must-see TV changes from being something that you watch every day to something that you got to check out right now, dude, just click here. And I think that really describes what what we have now with YouTube.

And they were asking, Well, what is this solution going to look like? How exactly is it gonna work? The VCs would love to invest in one.

And as I was reading this, I think it was pretty clear that BitTorrent would probably not be a part of the solution, at least initially, because BitTorrent works really well for very large files, but it's not really a good solution for this on-demand video service. First of all, because, for example, there's no bandwidth guarantee. If you download something on BitTorrent, it could take six hours or it could take six weeks--there's absolutely no way to know. And it's also not a good way to find things. It's more of a transfer mechanism. And so I was actually thinking, Well, what would the best solution look like?

And right after reading that article, actually, the tsunami happened.

And this is a significant event in the history of internet video, because it was the first disaster captured on cellphone cameras. And that would not have been possible even one year prior to then. And because it was an unpredictable event, it meant that CNN wasn't there to film it. So most of the footage was filmed on amateur video cameras.

And of course, most of the views occurred online because people wanted to see these amazing clips and were sharing them with other people. And there's actually one clip in particular that I remember that really struck me, which is this one.

I think it was very clear at this time that a better solution was needed.

And so the question was, Well, what if there was a video site where anyone could upload videos and anyone could watch them?

This is essentially nothing more than Flickr or HotOrNot, except for video. And all the other pieces had already been proven. We had already seen that community sites were very feasible, that the scalability issue could probably be overcome, and that it could possibly be profitable.

So the only question really was, Well, would it really work in terms of--would people really use it? I'd certainly worked on a lot of products before that I ended up releasing and no one used them. So it's difficult to predict what will be popular.

And the other question is, Well, why now?

Why is this the time to develop such a service? Because if you have a good idea, and it hasn't been done, then there's a reason that it hasn't been done. Because it's unlikely that you're the first person ever to come up with that idea.

So I think there were a number of reasons that prevented a product like YouTube from being possible until when we started developing it approximately.

And this is because of so-called secondary technologies, or you could call them on enabling technologies.

So these are really technologies that the end user doesn't really care about, but it's the thing that makes your product possible.

First one is broadband in the home. That was not really available everywhere until about that time when YouTube started. I mean, I remember moving to Palo Alto, which is right next to Stanford, in 2000. And I was sitting in my new apartment and I wanted broadband. So I call up the phone company, and they said, No, sorry. Actually, the fastest internet access we can give you is 28.8 dial-up. And that was in Palo Alto, the Mecca, the technology Mecca of the world--next to the Stanford campus. So even in 2000, broadband was just not available. And you can't, of course, have a video website on dial-up--it wouldn't work.

The other enabling technology that was important that had to be in place is Macromedia Flash Seven. So Macromedia is, first of all, exists in almost every browser on every operating system. And one of the major innovations that YouTube had was that we decided to use Flash for the video player. And that's sort of taken for granted now, but at the time, that was actually a very novel innovation. And so Flash Seven was the first time that Macromedia included video capability in the software. And without that, I think we would not have been able to use the Flash video player.

And to get the viewers on YouTube, you need the content. So where does the content come from?

Well, it comes from these hundreds of thousands of video clips that are created around the world every day on amateur video cameras. And I think this was also the right time in terms of that because even one or two years prior to that, people weren't really buying digital video cameras, and they weren't making these clips.

In fact, I remember, around maybe 2003, a bunch of people had digital video cameras but they didn't actually know that they had them. They just went out to buy a digital photo camera, and well, it came now with video recording capability. And so I would always ask my friends, So hey, did you take a lot of videos on your last trip? And they'd be like, Oh yeah, I didn't know I could actually do that, or, Oh yeah, I actually, like accidentally, selected the video mode and I made a video, and I didn't know, I thought I was making a photo or something. So this was also around the time when this really took off.

And finally, cheap, dedicated hosting bandwidth. So clearly, this was needed to make something like YouTube work, where the bandwidth is substantial. And prior to this point, I don't think the bandwidth cost could have been outweighed by the ad revenue. But I think this was sort of the inflection point where that became possible.

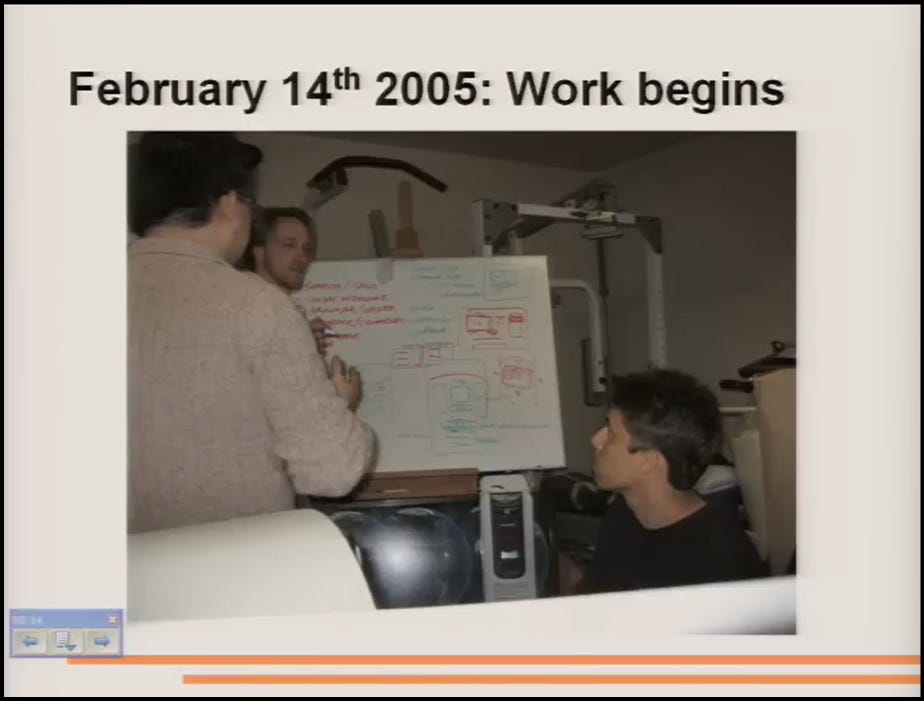

And so, based on these factors, we--the three of us had been talking about starting up a company for a while, and we were considering this idea of a video sharing website.

And we all thought it was a good idea. I mean, we didn't outline it exactly like I am doing today, of course, but we were sort of thinking through all the problems and why is it possible now and why not before and what does it solve?

So on February 14, 2005, which of course is not long ago at all, we started on YouTube. And let me just give you some background.

So on the left, that's Steve Chen. And he also went to U of I. I believe he left in '99 to--he was hired by Max Levchin to go work at PayPal.

Chad Hurley in the middle was the first designer at PayPal. And he is really a sort of user interface expert. These sort of skills are really difficult to find, and even to develop. He's someone who--he has an art background, and design background. And he is really able to come up with interfaces that are just easy to use, and very effective.

And Steve and I, together, had been on the PayPal architecture team. We were among the earliest engineers, so we we helped scale the service from a couple hundred thousand to over 60mn users over five years. And I think the experience we gained from doing that was just something that you just--you can't--you really can't teach that or learn it in a class. You really have to do it. And at PayPal, we had the opportunity to work with a lot of extremely talented people. And we actually ended up hiring many of those to help us out at YouTube.

So by April 23rd, we had the site implemented.

And this is the first video.

So we launched the site, we had a bunch of stupid videos. No one was really uploading videos other than us, and we had no users. So one thing we did is, well, we pitched it to a bunch of people.

I showed it to a bunch of my friends, and most of them thought it was pretty good idea. But some weren't sure. Some said, Well, I don't know if anyone would use that.

We also--I remember we wrote to all the Wired reporters that we could find. And we said, Hey, you should really write about this. We think it could be big--we don't know--but it's an interesting product. And no one replied. We didn't get any replies. And of course, now it's hard to pick up any copy of Wired that doesn't mention YouTube.

And also some--we talked to a bunch of VCs early on, just to get their reaction. And a lot of them didn't call back, or they thought it was a cute product, but--some of them said, Well, that's cute, but what are you going to do with this?

And so the thing that I kind of learned from this is that just because so-called experts reject your idea doesn't necessarily mean it's a bad idea. And the other thing is that in certain areas, there are no experts. Because the the thing is, if they were experts, why didn't they develop this? So I think if you're doing something new, then you are basically the expert.

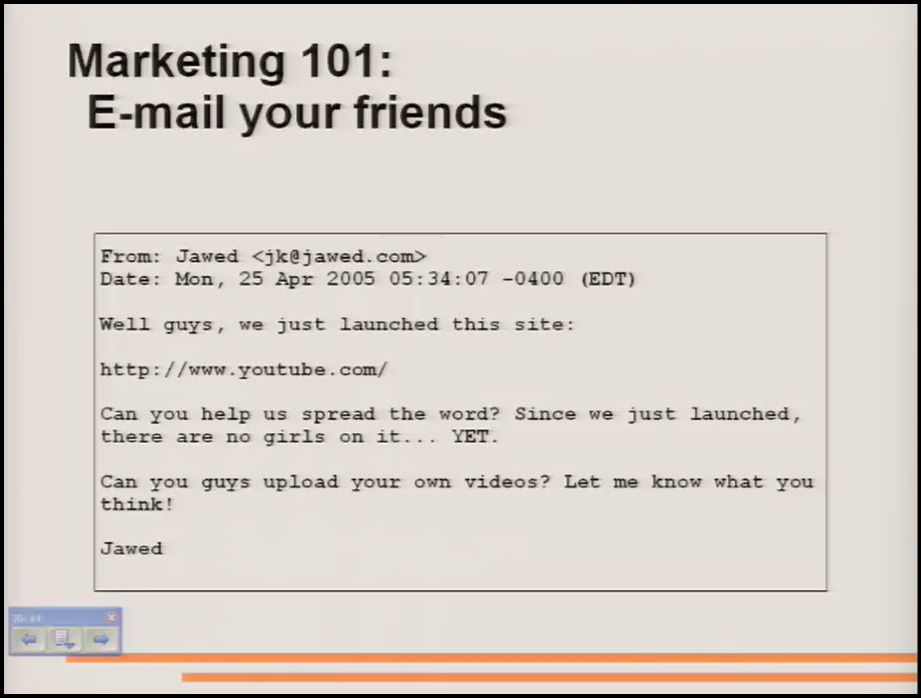

So the easiest way to market a new website is you email all your friends. And the reason we did this is because we... [audience laughs at email].

I actually talked to the guys who started HotOrNot. And they said that all they did is they built the website in like a weekend, then they emailed all their friends, and then they never did any marketing again. And it just took off like crazy from there. So we thought, Okay, well, we have a product that's sort of similar in some ways, let's try this. But this didn't actually work all that well.

And so at this point, by May, it was quite frustrating. The site had not really taken off, and here we are discussing the situation in the garage.

So we're pretty desperate at this stage. And we were trying to come up with ways to get more videos and more users.

And of course, if you get girls on the site, that's the best way to attract more users. So we actually went on Craigslist in the Los Angeles area, and we made a bunch of posts and said, Hey, if you're female, and if we think you're attractive, and if you make 10 videos and you upload them, then we'll send you $100 with PayPal. So that was going to be our strategy... but actually, we didn't get any replies to that. So yeah, it was pretty frustrating.

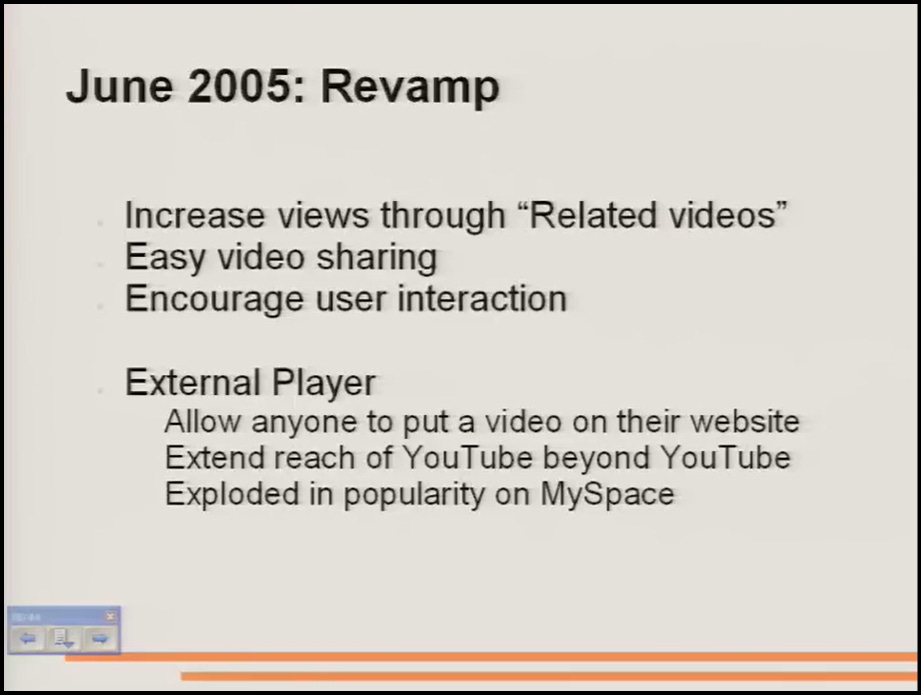

So by June, we were like, Alright, this is it. We're gonna do a complete revamp, because this is obviously not working. So we really changed the concept of the site.

First of all, we added this related videos window that you now see. And this just encourages people to watch more and more videos. So if we get them to the site once, watching one video, if we can find something that's related, chances are, they'll just continue watching.

We also made it easier to share videos with all your friends. So rather than us spamming everyone, we actually left the spamming up to our users, because they would just enter email addresses of their friends, and they would just click one button, 100 emails went out, and all those people would come back. So that worked really well.

And then we also added more social networking features that encouraged user interaction. So the idea was people spend more time on the site, talking to other users, finding out what other users' favorites are, and things like that, then, well, they'll just end up watching more. And they'll also end up sharing more, and bringing in even more users.

I think one of the most important innovations at the stage was this external video player, which is really very simple. We have a HTML snippet next to each video, and if you just copy it and paste it onto your own website, then basically you have a YouTube video player on your website. And that was pretty cool, because prior to that, it was really hard to put a video on your own website. So this allowed anyone--this basically allowed people to be on YouTube even if they weren't on youtube.com.

And it extended the reach to sites such as MySpace. And actually, this feature became extremely popular on MySpace. And I think that's one of the many reasons that we took off so quickly back then.

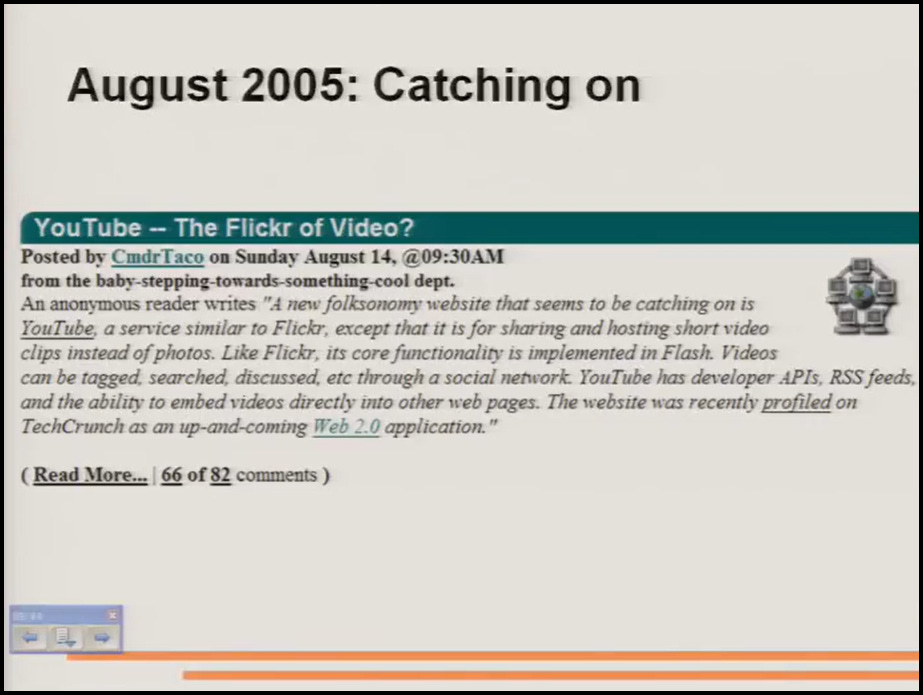

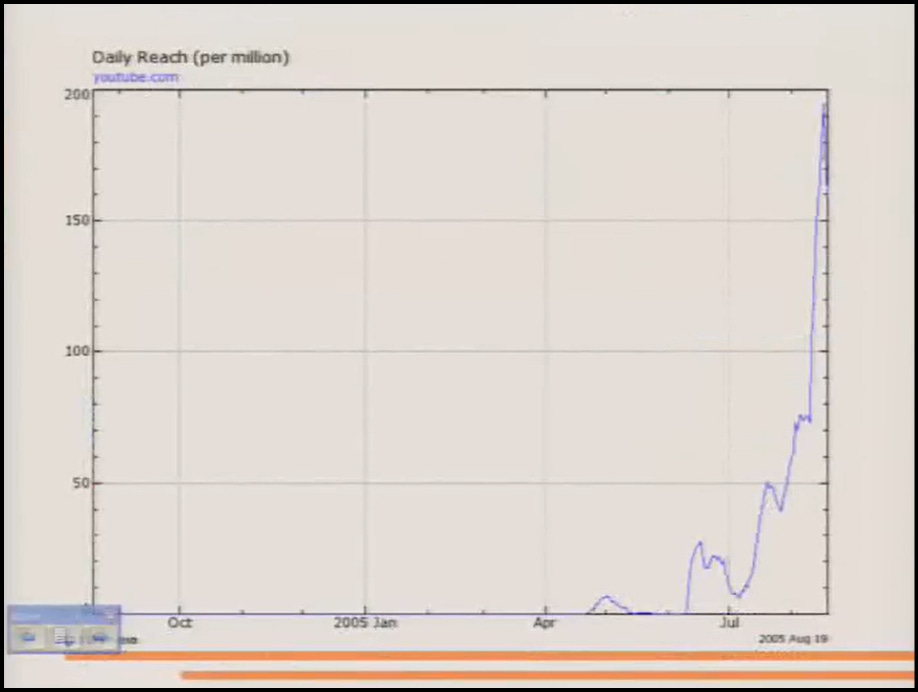

So by August 2005, I think this is when we first knew we were really catching on.

And I think--yeah, when we were posted on Slashdot, that was definitely pretty cool because it brought in a lot of traffic. And it never really dipped below this traffic level after the spike from Slashdot.

And back then, people were describing us as the Flickr of video, which back then was a pretty decent way to describe the product. And so we were kind of trying to understand--we were reasoning through our growth and trying to understand why we were growing so quickly.

And one thing I remember is, initially, we were getting just a few hundred video uploads per day, but every two weeks, there would be one video clip, which would be a totally random clip, that just went through the roof. And it would be so popular it would just dwarf all the other video clips. And this happened maybe every two weeks, initially.

But the thing is that the rate of video uploads was increasing. So we were getting--first 50 videos per day, then 60, 70. And so we were reasoning, Well, if we get more videos per day, and the probability that a video is a super hit is fairly constant and can't really be affected, well then eventually, the probability that we get a really big hit just keeps going up.

And that's actually exactly what happened. The time period between these really viral videos decreased to the point where now, actually, every day, there are many, many such clips on the site.

And one thing that we didn't--one thing that we couldn't really predict that kind of surprised us was the way the community drove the site.

Now, we had predicted that the community would be the core part of this website, but we hadn't anticipated the ways in which they would use the website. For example, what they would do is, someone would post a video discussing something or doing something, and then all these other users would reply to that video, and they'd be like, Oh yeah, I saw your video, and I think what you said is like, totally lame, or really cool, or whatever. And so they created this concept of video responses.

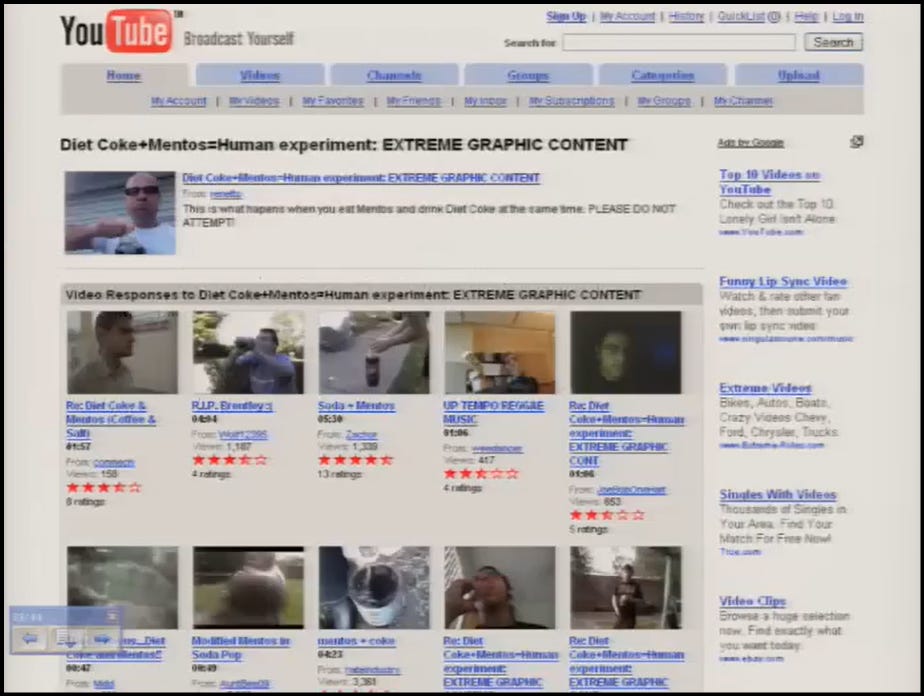

So what we did is, we basically created a product called video responses so that people could more easily understand the connection between videos. And this is just a random example I pulled up--actually, could we switch to Firefox that's currently running--that has this video. Yeah. Just go ahead and play on that.

Yeah, so actually, don't worry. He posted a follow up video where he said that he was just joking. Yeah.

So I thought this was interesting--where people just posted their responses, doing the same stunt with the Mentos. And so we really came to understand that the community is driving this product. They are figuring out new ways to use it, and what we're going to do is we're just going to accommodate that, and basically allow them to use it in whichever way they want to use it.

So this is a list of video responses that people uploaded for this particular one.

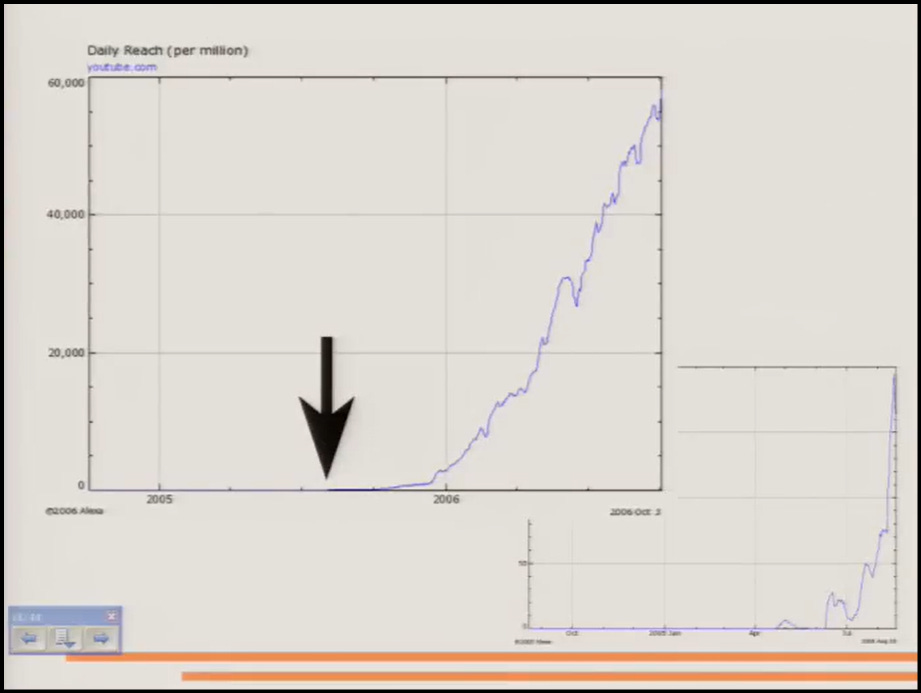

And so it's also around this time that we started pitching the business to VCs. And pretty much the only data we had was stuff like this graph on Alexa, which is not very much data.

It's only from April to August 2005. And we would go to these VCs and we'd say, Hey, this is our product. Let me give you a demo--this is how it works. And we think it could be very popular. And we think this trend will continue. But of course, no one knew if it would. I mean, we thought it would. But you sort of have to have a lot of faith in the product to assume that it will. But we thought that we were filling such a big hole--basically there was such a huge need that was not being met, which was video on the internet, that we were confident that things were just getting started.

And the interesting thing is, to put this in context, this growth is really just this on the overall growth graph.

And so really, things did continue that way, and they're continuing to grow.

And so we were able to raise $3.5mn from Sequoia.

And the interesting--it was also an interesting experience to talk to these VCs--just seeing how they reacted differently to the product, and how different firms had sort of different approaches.

And the one thing that was really interesting about Sequoia is, I think they were the only VC firm that we talked to that really approached YouTube as both a product as well as an investment. They were actually--the day after we pitched it to them, we could actually see in the database that like the entire office at Sequoia had signed up, they were all uploading videos, sharing videos, their secretaries were using it, and they were just going wild with it.

And really no other VC that we had shown this to had actually done that. The other ones--most of the other ones simply looked at it as an investment, but they didn't really get into the product as much.

And raising this capital allowed us to do a few things. First of all, of course, hire more people, pay for bandwidth, and upgrade hardware. And also, it allowed us to pay for some marketing promotions, such as, we were giving out one iPod Nano every day for a few months, which definitely helped a lot as well.

So one question is, Well, what's next? What's the next big thing?

And well, no one, of course, knows until they try it out.

But I think what's clear is that the next big thing will exploit newly emerging secondary technologies. So a lot of these products that are going to be the next big thing are not the current big thing because they're just not possible yet. So I think these newly emerging technologies, secondary technologies, will come along and will enable one to build something that wasn't previously possible.

So one way to find the next big thing, I think, is to just watch these enabling technologies that may not even be getting that much attention, but they are what will make the product possible. And of course, like many popular products, it will finally be something that makes something that was previously difficult easy.

And that concludes this talk.

If you got this far and you liked this piece, please consider tapping the ❤️ above or sharing this letter! It helps me understand which types of letters you like best and helps me choose which ones to share in the future. Thank you!

Wrap-up

If you’ve got any thoughts, questions, or feedback, please drop me a line - I would love to chat! You can find me on twitter at @kevg1412 or my email at kevin@12mv2.com.

If you're a fan of business or technology in general, please check out some of my other projects!

Speedwell Research — Comprehensive research on great public companies including Constellation Software, Floor & Decor, Meta, RH, interesting new frameworks like the Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3), and much more.

Cloud Valley — Easy to read, in-depth biographies that explore the defining moments, investments, and life decisions of investing, business, and tech legends like Dan Loeb, Bob Iger, Steve Jurvetson, and Cyan Banister.

DJY Research — Comprehensive research on publicly-traded Asian companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Nintendo, Sea Limited (FREE SAMPLE), Coupang (FREE SAMPLE), and more.

Compilations — “A national treasure — for every country.”

Memos — A selection of some of my favorite investor memos.

Bookshelves — Your favorite investors’/operators’ favorite books.

Yeah. That one was brilliant!