Letter #65: Peter Kaufman (2020)

CEO of Glenair & Editor of Poor Charlie's Almanack | An Unsung Hero

Hi everyone! Due to popular request (and a few persistent individuals), I’ll be restarting this newsletter, but with a few changes. Most notably, rather than sending “A Letter a Day”, I’ll be sharing a letter or transcript twice a week, once on Tuesday afternoon (2:22pm) and once on Saturday morning (6:06am). Second, I’m expanding the scope of the newsletter to include a broader range of subjects, but still focused on thought-provoking investors (across venture, hedge funds, and private equity), founders (not just tech), and operators (sales, marketing, product, etc.). Lastly, I’ll be limiting my commentary so it’s a smoother reading experience and you can read the work as is. (If you’d like to see my notes or trade thoughts, shoot me a DM on Twitter!)

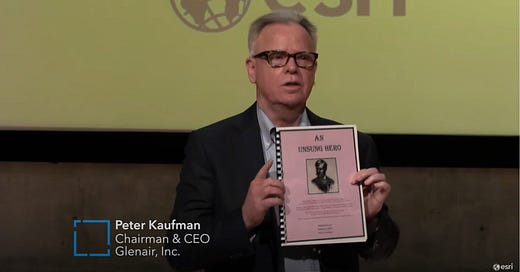

Today’s letter is a transcript of Peter Kaufman’s speech at the Redlands Forum in 2020. In this speech, he shares the story of Frederick Taylor Gates, who he argues is one of the most impactful people in history. John D. Rockefeller said Gates was the best businessman that he ever encountered (and he had encountered both Andrew Carnegie and Henry Ford). Bill Gates and Warren Buffett said that Gates’ memoir was the most thought-provoking book they’d ever seen on philanthropy.

Peter is the longtime chairman and CEO of Glen-air, a multi-billion-dollar aerospace company that creates and distributes mission-critical interconnect solutions. He is also the editor of Poor Charlie’s Almanack (which I have based many of my compilations on), one of the greatest books of all time, and recommended by people such as Warren Buffett, Lu Li, Bill Gurley, Bill Gates, Naval Ravikant, and Josh Wolfe.

I hope you enjoy this speech as much as I did!

(Transcription and any errors are mine.)

Transcript

Speech

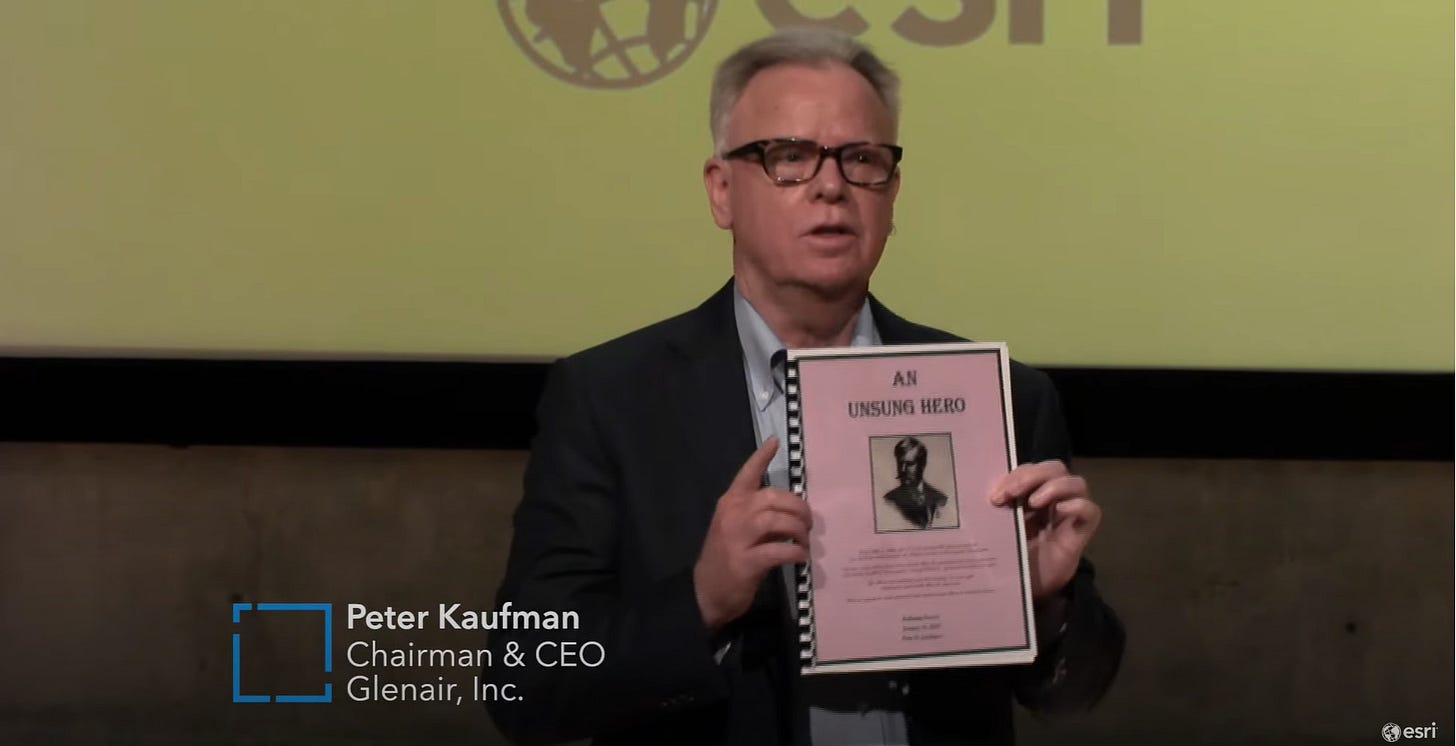

This is our unsung hero by the way [holding up a booklet with a picture of man on its cover], and the mystery is: who is this man? Because I’m going to argue that this man has had more of an impact on all of our lives here tonight than almost anybody else we can think of. And yet, unless some of you are very astute historians, my guess is you’ve never heard of this man.

Now, to properly frame this talk, I have an apple. There’s this beautiful Zen line that I really love. it says that anyone can count the number of seeds in an apple, but very few can count the number of apples in a seed. Isn’t that beautiful? Okay? So the first half, counting the seeds in an apple, that’s a finite life. The second half, counting the number of apples in a seed, is an infinite life, additive sum. And this man I’m going to talk about tonight, boy did he ever nail the infinite life, did he ever leave the world a better place than he found it.

By the way, as you leave tonight, you [can] all take home a copy of the story, okay?

From 1880 to 1888, these are ages 27 to [34] of our unsung hero. He was the uncommonly honest, pious, and hard-working pastor of the lowly Central Baptist Church in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He was not without a sense of humor, saying his church was mainly populated by those made to feel unwelcome at the fancy First Baptist Church of Minneapolis. He was born on July 2, 1853 in Broome County, New York. Graduated from the University of Rochester in 1877, and from the Rochester Theological Seminary in 1880. He was obsessed with living a life completely aligned with strict religious beliefs, and in his first stint as a pastor he was working himself to exhaustion. But this extreme ethic – work ethic and piousness was noticed around town. And one day [as] he’s working in his office, there’s a knock on the door. And he looks over to see who’s coming in, and he is shocked, absolutely shocked, to see it is George Pillsbury. The leading citizen of Minneapolis, the flour baron. Now, George Pillsbury was not one of his congregants. Where do you think George Pillsbury went to church? Exactly right. Jack, Laura, this is a very astute audience you have here tonight.

An account survives of this meeting in our young pastors own hand. The effects that still unfold from this meeting, 132 years ago, [continues] to profoundly affect all of our lives here tonight, and all those in America. In fact, I would argue, that such effects are among the most impactful and transformative in American history. Now you are probably thinking, Peter’s setting the bar way too high here, okay. How in the world is going to live up to this intro? But we’re going to clear that bar. Now if you’ll bear with me for a minute, I’m going to do a little side bar. Before I recount the events of that historic meeting, I want to take a short detour, and I think it’ll be worth it. It’s the why.

Just why was this man able to do all the amazing things that I’m going to tell you about tonight? I say the answer comes from simple chemistry. A chemistry model that perhaps offers the greatest potential for self-improvement for any human being. And I hope after you hear this chemistry model, I hope you share it. With your children, your grandchildren, with everyone you know. Because I think this is the best pathway to self-improvement that’s available to any of us.

Now, in chemistry there’s a scale of hardness called the Mohs scale. M-O-H-S.

Diamond is the hardest substance, it’s a 10, and baby powder is the weakest, it’s a 1. Now on the Mohs scale of hardness, tin, which I just happen to have, some tin here, is only a 1.5 on the Mohs scale of hardness, it’s very weak. I’m going walk all the way over here, as far away as I can get. I’m going to put the tin there, and while I’m walking all the way over here, I’m going to talk about copper. Copper on the Mohs scale is only a three. If we have a 1.5 over there and a three over here. why am I separating these two like this? Because in nature, for whatever reason, tin and copper are not generally found in the geographic proximity of one another. And as I will ultimately connect up, that’s the beauty of this model. they’re not generally found in the geographic proximity of one another.

Now, somewhere all along the line in history, somebody had a very bright idea: I wonder what would happen if I went way over here and got some tin, and then went way over here, reached way across, to something not generally found in the geographic proximity of tin, namely copper, and I blended them together. Now arithmetically, what should we get? 1.5 plus 3 is 4.5, divided by 2 to get the average, we should get 2.25. Do we get 2.25? No. I wouldn’t be telling this story, would I, if you have 2.25.

Does anybody know what you get when you blend tin and copper to get – not Dave Sorensen. Dave Sorensen is an expert in metals. Brass is close, but not – bronze – who said bronze? You see me afterwards. I have a prize for you.

You get bronze. Now, does anybody know what bronze is on the Mohs scale of hardness? We know it’s not 2.25. I’ll give you a hint – who said 6? You see me afterwards as well.

It’s a 6. Iron is 5.5. Can you imagine taking two independent characteristics, neither of which is all that powerful, and putting them together in just the right way, and getting a 6? Now, in physics, they have a name for this. It’s called a leaping emergent effect. Now, what if in your own life you could put together some characteristics and become bronze yourself? Become a 6? What would you need to do? Well, you need to identify what kind of a person am I? Am I tin? Am I copper? What would I need to reach across and blend into myself? Okay?

Now, in terms our unsung hero, I’m going to argue that the reason he was able to accomplish what he did, and the reason you’ve never heard of him, is because what he blended in together was something you almost never see. He understood the world from the bottom up, and he understood the world from the top down. In the military, we see NCOs. they understand the world from the bottom up. We see generals, they understand the world from the top down, okay. They’re fighting with each other all the time, aren’t they? And every once in a while, you get a George Marshall. What was George Marshall? He was bronze, wasn’t he?

He understood it from the bottom up, he understood it from the top down. And our unsung hero’s one of the best in history at blending bottom up understanding and top down understanding. but that’s also why you’ve never heard of him. Because the people who blend these two characteristics together, are they ever a self-promoter? No they’re not, are they?

This auditorium that we’re in tonight, this building that we’re in tonight, who were they built by? This couple over here. They have that rare combination, don’t they? They understand everything from the bottom up, they understand everything from the top down. Are they self-promoters? No. This is a beautiful combination. I wish the world was full – I wish our country was full of bronze leaders, but it isn’t.

We’ll go back to our story now.

I’ve told this story 50 times, and every time I tell it, it surprises me again. I said this is impossible, one human being could not do this. Okay, here’s what happened when George Pillsbury comes in. These are the words of our unsung hero, from his memoirs, word-for-word.

Mr. Pillsbury said he wished to have a little conversation with me, which he would be glad if I were to regard as confidential. While to outward appearance he was hale and hearty, such he said was not the fact. His physicians had warned him of an insidious and incurable disease that must in no long time terminate his life. In other words, he’s dying. He said he had made in his will a bequest of $200,000 towards a Baptist Academy, an educational project. But, he said, I’m concerned my gift will be neglected, and I’m contemplating a change in my will. I don’t trust these people. I don’t want to leave them $200,000. I don’t trust these people.

Okay? Why is he talking to our young guy? Because I trust our young guy. I’ve watched our young guy. There’s nothing not to trust about our young guy, who’s 34 years old.

He said he had come to me for any counsel I might give him, or were his doubts justified? if so, could I suggest a way of correcting the situation as to render it more assuring. I asked him to give me a little time for reflection on his problem.

Okay, now this is me talking. I have a deep, deep background in development work. I’ve chaired several capital campaigns and advised many others. But I am aware of no story that approaches the one you’re about to hear when it comes to sheer top-down bottom-up genius in development work. Like a first domino, the way our pastor responds to Pillsbury’s problem sets into motion a series of effects that forever change the young man’s life, and in turn the whole world.

Remember, he’s only 34 years old, but already the George Pillsburys of the world are noticing the unusual combination of factors present in this young man and seeking him out for counsel. So what does our pastor do? He goes to work on his assignment. he embarks on a due diligence tour to understand every last nook and cranny of what the educational structure should optimally look like in the Minnesota area. His tour brings him into contact with every Baptist of note in the state.

From this huge bottom-up dataset he amasses, he develops a sound top-down big-picture plan and submits it back to George Pillsbury. Here in his own words is the four-part plan he submits. Not just for any Baptist Academy, no. For the optimal Baptist Academy.

Such an academy must be well endowed and equipped. A much better school than the ordinary high school. It should be modeled on such great Eastern schools as the Phillips Exeter Academy. Similarly, with hundreds of thousands in endowment. To convince Minnesota Baptists of the value to them and their children of a well-endowed Academy, a series of popular addresses can be given from influential pulpits.

Success for such an Academy will only be assured if local Baptists themselves contribute a considerable sum. where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.

Instead of your $200,000 pledge, Mr. Pillsbury, you should offer conditionally to give say, $50,000 to the Academy, provided the Baptists of the state first contribute an equal sum. funds that I will go out and raise myself.

Of the hundred thousand thus raised, half should go into a needed new building and the other half into endowment. With proper safeguards in place that all this proves successful, with confidence, you can then safely leave the remaining $150,000 in your will.

This is awesome. Just awesome. Superb top-down and superb bottom-up. In the history of large-scale development, has anyone ever turned down a major gift in exchange for the privilege of going out and raising a big chunk of money themselves, only then to be matched and then propose contingencies for the remaining estate gift?

Needless to say, George Pillsbury is bowled over. Our young pastor gets the green light. He forms the committee. He heads it up. He speaks everywhere to talk up the plan. From bottom to top, he raises the money, inspiring and energizing the community. These instincts as we will see, for informed engaged top-down bottom-up interaction, will go on to benefit him enormously.

The project succeeds. Magnificently.

His work comes to the attention of a group of Chicago-area Baptists, including Dr. William Rainey Harper, who have been trying for years to interest New Yorker John. D. Rockefeller, the richest Baptist in the world, in founding a Midwestern Baptist University – one to rival the Ivy League schools of the East.

But they have been singularly unsuccessful in such asks to the oil titan. In fact, they have been so clumsy, Rockefeller has banned them from ever calling on him again. But in watching the awesome development skills of this 34 year old pastor, Harper and his group think they may have a second chance.

Young pastor, they ask, will you go see Mr. Rockefeller on our behalf?

Armed with a formal letter of introduction from Dr. Harper to Mr. Rockefeller, our unsung hero agrees to travel to New York to take a shot. But Rockefeller won’t meet with him. Refuses. I’ve been through this before. Not going through it again. However, he says, I’ve been watching you at a distance. I’m very impressed with you. if you want to write me a letter, you can write me a letter.

Our pastor writes him a letter. It’s the perfect letter. He just nails it. In previous asks, Rockefeller has been repulsed by the haste advocated by Harper and others. too big, too fast. Not respecting the details. in stark contrast, our pastor’s letter suggests a methodical, bottom-up, incremental step-by-step approach. an exact match for Rockefellers lifelong temperament.

He says, Mr. Rockefellers ideas happen to coincide with my own. Happen to coincide? It was no coincidence. our hero is a natural. How many 35 – he’s 35 by now. How many 35 year olds have a blend of top-down, bottom-up thinking in perfect harmony with that of the richest man in the world? A financial titan who made his fortune combining these very traits himself? You can see why Rockefeller was so impressed with this letter. There’s a letter from a 35 year old – he goes: I could have written this letter myself.

Time does not allow the reading of the full masterpiece of a letter, but it survives to this day. here is the money paragraph that so resonated with Rockefeller:

“All things come to him that waits. Our best and greatest schools have developed broadly and hardly step-by-step in this way. holding the possible scope of the institution and abeyance for a few years will cost nothing, while time will of itself solved the question easily and with certainty.”

The letter is such a home run with Rockefeller it results in an invitation to go visit him in person in New York. Our young pastor makes the ask face-to-face, and the rest is history. Rockefeller becomes the funding founder of what becomes – anyone? The University of Chicago!

Our kid is all of 35 years old! He’s responsible for the existence of the University of Chicago. Would not exist without his ask. Wouldn’t have existed without the George Pillsbury exercise that came before. If our story ended here it would be worth a big fuss. Imagine a 35 year old pastor being responsible for the very existence of the University of Chicago and it’s over 100 Nobel Prizes.

But the story doesn’t end here. It only gets more and more incredible. For Rockefeller is so taken with the bronze-level talents of this young man, he requested my early removal to New York, especially to help him with his benevolences. Meaning all the people that are pestering him, asking him for money all the time. when it came to philanthropic solicitations, the tycoon was constantly hunted, stalked, and hounded, almost like a wild animal.

He relocates to New York City and is put in charge of all of Rockefellers philanthropy. Using what he calls wholesale scientific giving, he begins to steer donations towards large-scale, focused philanthropy for the betterment of humanity. More on this later – much more.

No surprise, his performance is so good – everything he gives this this kid. Rockefeller decides to put even more on his plate. Will you on your travels, Rockefeller says to him, take a quick look at some of my non-Standard Oil investment properties throughout the country?

Yes, he says. He responds by visiting three of Rockefeller’s principal non-Standard Oil investments: an iron furnace in Alabama, a mortgage on a steel mill in Wisconsin, and various mining properties in Colorado. Like a great detective, he seeks validation of the legitimacy of each property. He verifies recorded documents and county record offices. he interviews objective third party of experts. He even chats up miners on a Colorado train.

He finds most of Rockefellers investments are worthless scams pawned off on Rockefeller by seemingly upstanding Eastern individuals and investment banks. Our kid’s the only one who figured out these are scams. Now, in this thing you’re going to take home later, is the whole chapter from this man’s memoirs where he tells you how he did this. It’s incredible. It’s like reading a detective story.

Extricating Rockefeller from these messes, he turns instead to an investment area his investigations deem is legitimate: the Mesabi Range of the Great Lakes region – which Jack you and I were just talking about this this morning. Taking amazing advantage of the aftermath of the panic of 1893, one of the worst financial plunges the US has ever suffered, he commits $33.5MM of Rockefellers fortune, amassing oil resources, mines, railroads, docks and building an [oar?]-carrying fleet of sixty vessels.

In 1901, he sells the properties to JP Morgan and US Steel for $88.5MM. That’s a $55MM profit in eight years. You know what that is in 2020 dollars? It’s roughly $1.5B that this Baptist preacher with no educational background in business, no business experience to speak of, makes his employer $1.5B in eight years. And John D. Rockefeller never set foot on any of those properties.

In an era of no income taxes, he makes Rockefeller 55MM large. Such performance led Rockefeller to later say, he was the greatest businessman I ever encountered in my life. Better even than Henry Ford and Andrew Carnegie. Well this is, this is impossible, isn’t it?

This kid is responsible for the University of Chicago, he makes what’s the equivalent today of a $1.5B in eight years all by himself? Yet this is just kid stuff. In 1897, our unsung hero prepares a memo for Mr. Rockefeller, and our show really gets rolling.

The story unfolds like this: when he first went into the employ of Mr. Rockefeller, he wrote to himself: medicine, as his generally taught and practiced in the United States is practically futile. He wrote that to himself. Does he have a background in medicine? No. But he does he care about humanity? Yes.

We’ll let him tell the rest of the story.

On a whim, four years later in summer 1897, with his family in the Catskills on vacation, he revisits the subject of medicine, having brought along for leisure reading, William Osler is 1,000-page textbook: Principles and Practice of Medicine. I’m sure that we all, when we go on summer vacations with our family, take along William Osler’s 1000-page textbook.

Now we’ll let him tell the rest of the story.

I saw clearly from the work of this able and honest man, perhaps the ablest physician of his time, that medicine had in fact, with only four or five exceptions, no cures or disease. Medicine could hardly hope to become a science until medicine was endowed, and qualified men were enabled to give themselves to uninterrupted study on ample salary entirely independent of practice. To this end it seemed to me an institute of medical research ought to be established in the United States on the general lines of the work of Koch in Berlin and the Pasteur Institute in Paris. And here was an opportunity for Mr. Rockefeller to do an immense service to his country and perhaps the world.

This idea took possession of me, he says. Mr. Rockefeller entertained my suggestion hospitably, as indeed I encouraged further and further detailed inquiry. It was in this way that my name became associated with the origin of the great Institute of Medical Research subsequently founded and so munificently endowed and equipped by Mr. Rockefeller. Anybody know the name of this institution? Rockefeller Institute. It’s now Rockefeller University. New York City. 27 Nobel prizes in medical research. It was the first Medical Research Institute founded in the United States exclusively devoted to figure out what? – how to cure diseases.

We’re almost done.

In 1905, seeing firsthand the impact that Rockefeller’s immense fortune was having towards humanitarian work on a great scale, our unsung hero pursues an entirely new vision: the establishment of the first permanent private foundation.

There were no foundations back then. We’re all familiar today with the Gates Foundation and the Walton Foundation – all these big – they didn’t exist. It was his idea – there should be a permanent foundation.

Why?

He says, it was not until 1905 that I ventured with many misgivings to approach Mr. Rockefeller with the question of the use and disposition to be made of his fortune. It might be argued that I was trespassing on a domain in which I had no proper business. But to myself it was very intimately my business, for I had come clearly to see that unless Mr. Rockefeller were to make some such disposition of his fortune, for a great part of it my life was doing more harm than good.

Rockefeller’s fortune was rolling up so fast that his heirs would dissipate their inheritance or become intoxicated with power unless we set up a permanent corporate philanthropy for the good of mankind. So at last I broke my silence. I wrote a letter. It is dated June 3,1905. This of course becomes the Rockefeller Foundation, which due to its highly complex nature was not officially chartered until 1913 – actually making it technically second in establishment to the Russell Sage Foundation. However, it appears Rockefeller’s idea was first.

In any event, over the rest of his professional association with Rockefeller, as he headed up this Foundation, he oversaw the distribution, Personally, of $500MM in philanthropy to benefit mankind, exceeding the $350MM overseen by the very well-known Andrew Carnegie.

Let’s recap, and even add some more factors. There once lived a man of top-down, bottom-up understanding. A non-self-promoting man. A man of honesty, piety, aptitude, and genuine love for humanity. A man likely you’ve never heard of, because he wasn’t a self-promoter.

Was called the greatest businessman of his time above Henry Ford and Andrew Carnegie.

Was perhaps the greatest development asker of all time at age 35, responsible for establishing the University of Chicago.

Conceived the world’s first permanent private foundation, then personally oversaw $500MM in distributions – that’s over $10B in today’s dollars.

Conceived the Rockefeller Institute and it’s unique research model.

Eradicated hookworm in the American South and the rest of the world.

Established black high schools in the south that allowed graduates to attend the best southern universities.

Finally, his most important move of all – one each of us and all Americans benefit from today – he sparked the 1910 Flexner report, establishing Johns Hopkins as the model for medical school education reform, which moved American medicine from the bottom of the barrel internationally to number one where it remains today. There’s not a person in here who hasn’t benefited from that.

Talk about an infinite life. Is the world better off because this man lived? His name was Frederick Taylor Gates. Now be honest, show of hands. How many of you have ever heard of Frederick Taylor Gates? Anybody? That’s the solution to our mystery.

I thank you.

Q&A

Host: I think that Peter will take some questions, right? If there are some questions. And do we have our fine mic runners, Dr. Walker and Mrs. Burgess? Thank you.

We didn’t get the word out to our students tonight. Not their fault, our fault. But these guys love to run stairs right, Shar? Okay, we got a question right up there, Shar.

Please introduce yourself and then ask your question.

Q1: Hi, my name is Anne. I’m just curious to know how long he lived and where he ended up. I mean, did Mr. Rockefeller, you know, honor him till the end of his life? I mean, I’m sure it’s in your book, but I want to know now.

PK: Well, it’s not in the book. It’s actually kind of sad. Because Rockefeller’s son, as sons tend to do, thought that he ought to be in charge of his dad’s foundation. And… he kind of got pushed aside.

He wrote his memoir, called Chapters in My Life, which hasn’t been in print, for you know 80 years or something. I bought the rights to that book, and I’m going to reprint that book. Because I think this is a story that needs to be told.

And I’ll tell you something else. I sent copies of this book to Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, several university presidents that I know with a note to each one of them. And I said, if you’re looking for a model for large scale philanthropy, how to do it right, it’s here in this book. This is how to do it right. It’s not just top down, is it? It’s bottom up. You have to know the details or you actually do more harm than good. So actually, it is rather sad. And perhaps it’s because he never promoted himself.

Any other questions? Yes.

Q2: Have you run into any other people that, similar to this, that perhaps we’ve not heard of, or have you–

PK: Well my best example I mentioned, is George Marshall of top down and bottom up. He’s been nominated by Stephen Ambrose, a historian, as the greatest man of the last 100 years, and I think that’s

correct.

Let me tell the D-Day story. I love telling the D-Day story. Top-down, bottom-up.

What’s the top down understanding of D-Day? Well it’s very simple. We have to stop Adolf Hitler. We have to. He may enslave the world. Millions could be killed. That’s the top-down understanding. So is D-Day necessary? Absolutely necessary.

What’s his bottom-up understanding? My stepson is one of the soldiers that’s going to be in harm’s way. I could lose my stepson, my wife could lose her son. Okay? Is that bottom-up understanding? You bet it is. What decision did he make? Got to go ahead.

When you combine top-down and bottom-up, you make correct decisions. So I’m sorry I can’t give you more names, these are very rare people – exceedingly rare – but boy do they leave their imprint on human civilization and we should be very grateful that they did so.

Q3: Okay, he was a very unusual man, but is this something that institutions, colleges, organizations can teach people? Or is this something [that] just has to come naturally?

PK: Well, let me ask you. What do you think? Do you think if you’d have heard this story when you were in high school, in college, do you think it would have made any impact on you? would it would you have lived your life any differently?

Q3: I think I probably would have, if I couldremember it – [I think] that you have to have a vision, I mean,you – you can learn – we all can have tools, but if we don’t have the creativity to know how to implement them, it doesn’t go very far. So as I sat there listening, I thought, well, what can I take from this, or what can we all take from this? He obviously was a detail man, but he was also a visionary. He obviously probably could write and communicate in a manner that the people he needed to convince understood him. So I’m just thinking, like you know, where can we go with this to improve what we do in our own organizations.

PK: Well, I mentioned earlier today an African proverb that’s one of my favorites. It says if you want to go quickly go alone, if you want to go far go together. And if you’ll notice, every single thing that Frederick Taylor Gates did, involved going together, didn’t it?

We’re going to stop and take the time to go talk to all the Baptists and find out what do they think the educational structure in Minnesota should look like. And then he said, and then we’re going to fundraise from all the Baptists, even the small donations. Why? Because where your treasure is – that’s where your heart is. He did a fantastic job of always staying together with the group.

So I think we can all learn from that. I speak at a number of different universities every year, and I can tell you they’re not all the same. And one of the great compliments I’ve given Shelley and her group on University of Redlands, is they are a go together, go far group. And some of the Ivy League schools I talk to, they’re not that way. They’re go fast, go quickly, go alone. So, hopefully, these things can be taught.

Now, this story has had an influence on at least one person, certainly influenced me. You know, grab my Apple again and hold it up. I want to live a life like Frederick Taylor Gates did. I want to do things that are additive sum, potentially infinite in nature.

Now this gentleman, stand up John – John Dorsey’s visiting from Greensboro, Alabama, and he has a program there that we’re currently having conversations with the University of Redlands regarding his program. It’s a Medical Fellows Program that perhaps Redlands students can participate in. And it’s one of the ways that I’m trying, in my own life, I’m supporting John to try to be like Frederick Taylor Gates.

I hope that one day we can scale this program across the whole United States, and deliver medical care as it should be delivered: community-based one-on-one. We’re moving in the exact opposite direction. I don’t need to tell anybody in this room that that’s what’s going on – digital files, artificial intelligence, doctors via Skype.

But our motto is that the only true remedy for whatever ails a human being, is another human being. John has a fabulous model for doing exactly that, and I hope after our work matures a little bit, John will come back and give a talk here to you and report on our progress.

Thank you.

John, why don’t you share?

[Can] we have the microphone?

John’s never going speak to me again after this.

JD: I was not prepared. Can you hear me? I really wasn’t prepared to speak tonight, so… But basically, I think most people in the room would agree that, sort of, healthcare is a mess right now and everybody’s looking for a solution.

And I don’t know that there is a silver bullet that sort of fixes it all. But one thing – when I came through medical school, I was extraordinarily frustrated and felt as though there were these good people: medical students, residents, nurses, [attendants] all working very, very hard – but there just seemed to be this odd disconnection where everybody seemed frustrated, and the patients seemed frustrated. And I had a hard time sort of understanding what was going on. Why was it that we were doing what we were supposed to be doing, but it just didn’t seem to be making such an impact?

And so I ended up doing a residency and community psychiatry – and how many of you guys know what community psychiatry is? So community psychiatry is basically taking care people are down and out, people who are in and out of homelessness, people who are in and out of incarceration, people are living in a lot of turmoil – drugs and alcohol – and that really crystallized to me what was the disconnect.

Was we were trying to provide technical solutions for things that were much broader than technical solutions could really address. And so I started to think about how could we develop a system that actually met the needs of the bulk of patients.

Because if you look in any emergency room setting, or family medicine setting, or almost any hospital, most patients, they may not be as extreme as that, they do have a lot in common with those sorts of patients. And I really wanted to sort of not only develop a system that address their needs, but really mobilize the next generation of community health leaders, college students, and medical students to really be part of shaping that future solution.

And so I moved to Greensboro Alabama about 14 years ago. Small town from Orange County. Made a trip across the country and landed in a small rural town down there and started a fellowship program for students who are between college and medical school to really begin to shape this and develop this model.

And basically, what we do is, as a psychiatrist or a family medicine doctor, you see 25 30 patients a day. they come in with a lot more going on than you can fix with medication or other things. We assign them to – assign fellows, we call them – students between college and medical school. Each of them are assigned around 10 health partners and they work with the patients and actually extend what I can do into the community and into the home and actually address the broader issues.

And it takes me from a position of where I feel powerless to actually empowered to actually make a difference in patients’ lives. And as the students really learn about this sort of – the human side and the community aspects of healthcare – and we extended that same idea not only into healthcare but looking into education.

So there’s very – there’s actually weird parallels between what’s going on in healthcare and education. If you think in elementary school you’ve got, let’s say take a third grade teacher, you’ve got 30 kids in your classroom, all at different academic levels, all different behavioral issues, all different attention spans, and they all end up in my office because they need medicines for attention deficit disorder.

And I’m like maybe that’s not entirely the answer for this. Instead, why don’t we take these same students who are working with health partners, and have them work in pairs in teachers’ classrooms to provide the one-on-one, sort of small group attention to the kids so that the kids who are behind can be caught up the kids who are ahead can be pushed forward and the teacher’s actually set up for success in managing the different sort of issues that the teachers are going through.

And what’s been remarkable, is if you think about it – Shelley and I were talking earlier – If you think what’s happened, I think broadly across the country, is these community-based, citizenship-based, non-professional initiatives, used to be by talented women who sort of ran sort of educational initiatives and healthcare initiatives. But the world’s changed, obviously, women are working and so you don’t have that infrastructure.

And so, really, my thought was, let’s take the next generation of students and really teach them about community-based citizenship where they can actually participate in reshaping and supporting that sort of structure in that community-based structure and actually make a difference within the healthcare system, in the education system.

So that’s kind of what we’re doing.

Q4: Can you describe… [inaudible]

JD: Yes. Yes. So we started out – so it’sincreasingly – when I went to medicalschool the idea was you graduate fromcollege and you went straight to medicalschool. That was just kind of the commonpath. More and more I think colleges – Redlands and most schools across thecountry and most medical schools – areencouraging students to take a year ortwo to gain a little bit of real-worldexperience and life experience. [There’s] more tobeing a doctor than just being a goodstudent. And so we – there reallyweren’t that many – or aren’t really anycommunity health gap year programs.

There’s Teach for America which focuses on education, but nothing really focusing on healthcare or community health. So 10 years ago we launched this program with three students. They spend one year with us, some stay on for a second year and take on a greater leadership role. We started with the three students. Over the last 10 years, we’ve had 90 students come through, with Peter’s generosity.

We started in Greensboro, Alabama. Tested a pilot in the next town over in Marion, Alabama to see if it really could be scaled, but that was very culturally similar. And Peter’s generously offered to support a pilot in Pomona, California to see if it could be done in California, a different cultural setting.

And that Pomona had a variety of reasons, Peter had been connected and knew the president of Pomona College, that’s where I went to college, and so it seemed like a natural sort of movement in that direction. And so we’re excited to have 12 fellows working with the schools.

One story I was telling, when we didn’t know how the partnerships we’re going to go with the healthcare organizations in the schools, so we approached the School District in Pomona, we said what would you think of having this group of students, twelve students, straight out of college, work with an elementary school, work with your teachers in grades K-5. And their response was how many of our 27 elementary schools could you work with?

We were like, we can start with one. So that’s – so I liked I liked Peters, sort of in his story, talking about take small steps, but incremental small steps. If you have a good idea, and you implement it properly and pay attention to the details, you really can over time. Because there’s no way when you take something as big as healthcare, it could just seem so overwhelming. That’s what I think everybody is trying to do – is take the Big Shot.

And that’s just not going to work. It’s just too big and too complex. But if you take small-scale steps, you can actually make a difference both at that individual level but then by preparing the community health leaders of tomorrow.

And I think that we really can grow exponentially in terms of the number of sort of health leaders who over the next 30-40 years, because it’s really going to be their system, and they should take responsibility for helping to shape the solution for the system.

PK: Thank you. Shelley?

Host: Oh, Jack has a question.

Q5: Peter, what caught your imagination and why did you do the research you did on this person? And I want to know more about who you are. What is it that’s motivating you? I mean you have had huge success in your career. You run a multibillion-dollar business. Why are you so interested in going bottom-up in communities making them work? I want to understand who you are.

PK: So I grew up in Santa Ana in a middle-class family. Went to public schools. But for a young kid, I had lavish tastes. I wanted a stingray bicycle. I desperately wanted a stingray bicycle. My dad was so cheap. He wouldn’t buy me my stingray bicycle.

So I started at age 13, sorting deposit bottles at the pantry market. They paid me in cash. you know, I’m super sure it was totally illegal what I was doing. But I really liked it I liked. I liked working with my hands and I liked making money and I was saving for my stingray bike.

Shortly thereafter, I went down and got a work permit, and I actually got a job as a busboy. and then I got a job at Hogue Memorial Hospital in Newport Beach working in the kitchen. One summer I spent the whole summer scrubbing pots next to Gabriel Guzman – an immigrant from Mexico – he didn’t speak a word of English. That’s why I speak Spanish. I spent the whole summer scrubbing pots talking Spanish, learning Spanish with Gabriel Guzman. Okay? Now I love Gabriel Guzman – he’s one of my most dear people I’ve ever met my whole life.

So I saw the world from the bottom, didn’t I? I saw it from the bottom of a range of institutions. And what did I see? Almost universally, how bad the managements were of all these institutions. My direct supervisors almost without exception were assholes. And they specialized in abusing down and kissing ass up. Now do you think we had any respect for these supervisors of ours? Of course we didn’t have any respect. But what about the people above them? We didn’t respect them either did we? Well, how capable can they be if this idiot is fooling them? He’s not fooling us and we’re high school kids. Okay?

So I saw all this, Jack. I saw it from the bottom. A series of fluke-ish circumstances brought me into contact with some masters, some mentors, who taught me what the top looks like. So suddenly, by a fluke, by accident, I’ve got the bottom, and I’ve got the top. And I just applied it. And did it ever work. Oh my god did it work.

And I’ve used it in everything in my whole life. I’ve done six major capital campaigns. Every time there’s a project that fails in Pasadena, a school project, they come find me. Let’s go get that Peter, you know, he knows how to do this.

Yeah, because I do it like Frederick Taylor Gates did. I go and talk to everybody. I get all the input from everybody. and what does that do? It designs the plan, doesn’t it? And then when you go to raise the money, everybody’s willing to contribute. Why? It’s their plan. they own it.

So, you know, that’s who I am. Part of who I am is, I love history. I just love learning from the past. And I studied Rockefeller and that’s what got me into Gates. Who in the world is this Frederick Taylor Gates? Rockefeller says he’s the best businessman that he ever encountered? Better than Henry Ford and Andrew Carnegie?

Well I’ve studied Henry Ford and Andrew Carnegie. They were unbelievably capable businesspeople. Who in the heck is this Frederick Taylor Gates? And I found this book. And I went out on the Internet – I have more disposable income today than I did when I was trying to buy that stingray bike, okay? And I bought every single copy that was available of Frederick Taylor Gates’ memoirs. I got like 24 of them, and the last few, is you know, getting scarcity. Where there’s scarcity, the price goes up. I paid $300 a piece for them. But what did I have? I had the inventory. And I sent them to Bill Gates and I sent them to Warren Buffett, and I got really nice letters back from them saying, you know, this is the most thought-provoking book I’ve ever seen on philanthropy.

But I’m going to take that book and I’m going to redo it and I’m going to put annotations on the side. I’m going to navigate the reader through the book and I’m going to try and make it – I’m going to target it – for these big, philanthropic family foundations. I’m going to send them all a copy of this book. They throw in the trash, they throw it in the trash. But maybe, maybe one of them, two of them will read this book and say, you know, this is correct. This is what our family fortune should be devoted to. And if we do it right, guess what will happen dear? We’ll go from being on the letterhead to being on a postage stamp.

And isn’t that what you really want in life? Be remembered on a postage stamp. His program has the has the potential to be a postage stamp program. It’s the best thing I’ve ever seen, okay? And I’ve been around. It’s the best thing I’ve ever seen. Do you mind if I tell the story of how it happened? That I called you?

This is, it’s kind of creepy, it’s kind of weird, okay? I don’t go to church. I’m the chair of the Cathedral in LA. I’ve been the chair since it opened, because Cardinal Mahony asked me to do it. He says, the only guy I know who could make everybody get along, okay? So I said okay, I’ll do it.

I’ve learned a lot doing it, but I don’t go to church. But I’m going through my mail one day—I get all this mail. I stand over the trashcan. I just throw it [and throw it into the trash]. And I come to the Pomona Alumni Magazine. I didn’t go to Pomona. I’m not interested in Pomona Magazine. And yet I couldn’t throw it out. My hand would not throw it out. Something in my head said you need to read something in it – I’m not making this up. I know it sounds weird – you need to read something in here.

I opened it up. I open it up to this page – and here he is standing there. It says, Something’s Happening in Greensboro. And it’s the story of what he’s doing. And I start reading this, like I had to get my yellow pen, I go get my yellow pen, highlighting almost the whole thing.

This is exactly – this is the model. This is the solution to the healthcare problem in America. And a guy, an unknown guy in Greensboro, Alabama is doing it. A top-down, bottom-up guy. John Dorsey.

Okay.

Wrap-up

If you’ve got any thoughts, questions, or feedback, please drop me a line - I would love to chat! You can find me on twitter at @kevg1412 or my email at kevin@12mv2.com.

If you're a fan of business or technology in general, please check out some of my other projects!

Speedwell Research — Comprehensive research on great public companies including Constellation Software, Floor & Decor, Meta (Facebook) and interesting new frameworks like the Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences.

Cloud Valley — Easy to read, in-depth biographies that explore the defining moments, investments, and life decisions of investing, business, and tech legends like Dan Loeb, Bob Iger, Steve Jurvetson, and Cyan Banister.

DJY Research — Comprehensive research on publicly-traded Asian companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Nintendo, Sea Limited (FREE SAMPLE), Coupang (FREE SAMPLE), and more.

Compilations — “A national treasure — for every country.”

Memos — A selection of some of my favorite investor memos.

Bookshelves — Your favorite investors’/operators’ favorite books.

Kevin, NickE really LIKEY! 🙌🏽

One of the best you have published.