Letter #90: Andrew Pastor (2021)

Partner at Edgepoint and Board Member at Constellation Software | Trust the Process

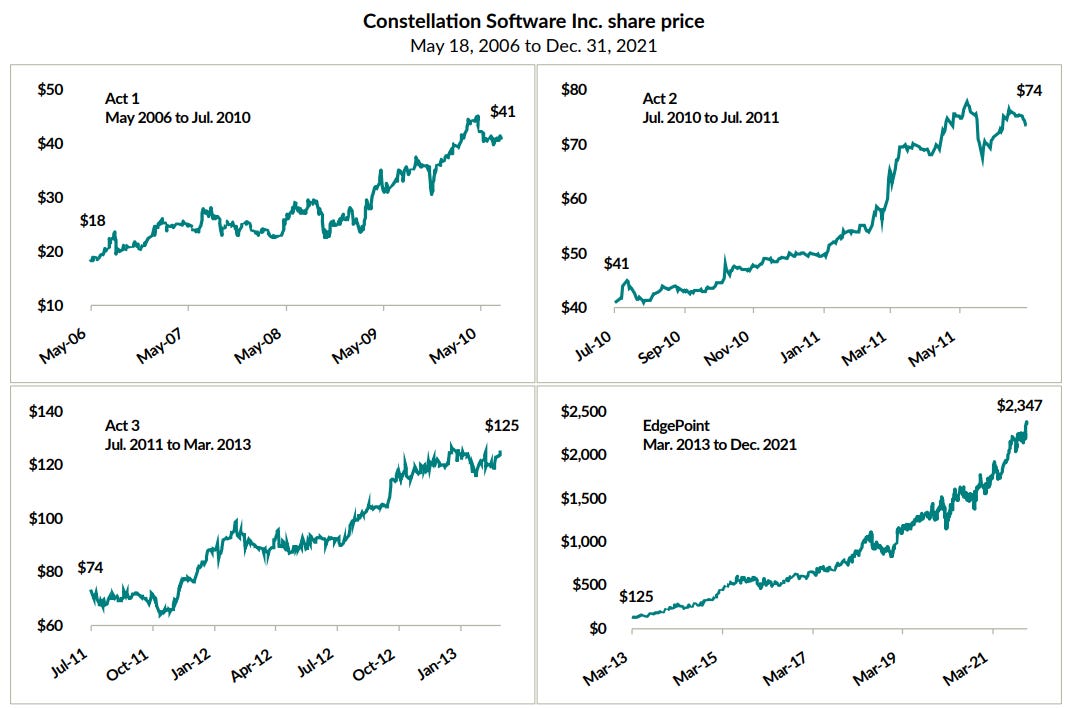

Today’s letter is an essay EdgePoint Partner and Constellation Board Member Andrew Pastor wrote in 2021 reflecting on how he generates ideas, starting with the story of how he discovered one of his best ideas on a golf course. He then discusses the repeatability of his process, reveals the shared characteristics of all of his ideas, shares the initial questions he thinks about when coming across an idea, and then lays out four of the key filters he puts his ideas through, along with concrete examples from his portfolio.

Andrew is a Partner at EdgePoint and a Board Member of Constellation Software. Andrew first became engaged as a consultant and observer to Constellation’s Board of Directors in 2016, and joined the board officially in 2020. Prior to joining EdgePoint, Andrew was an equity research analyst at Sionna Investment Managers from 2010 to 2012 and previously spent four years at BMO Harris Investment Management.

Relevant Resources:

Letter

We often get asked how we find our businesses, so I’m going to begin this commentary by describing how I almost missed discovered one of my best ideas.

Act 1

One of the most important moments of my investing career happened in the summer of 2010. I just didn’t know it at the time.

It was a beautiful Sunday afternoon and I decided to go golfing. Arriving late to the course, I was paired up with three strangers. As we walked down the first fairway, one of my playing partners (we’ll call him Mr. M) turned to me:

Mr. M: Andrew, what do you do for a living?

Me: I work in the investment business.

Mr. M: Half of the golf club works in investments! What do you actually do?

Me: Well, I’m a big fan of Warren Buffett. I’m not as smart and we manage (a lot) less money, but I try to invest like him.

Mr. M: It’s funny you say that. I’m the director of a public company and they talk about Buffett all the time.

Me: Really! What’s the company?

Mr. M: Constellation Software.

If you’re a golfer, you know that four hours leaves a lot of time for small talk and stock tips. I had grown accustomed to stories of why “this is the next Amazon” and learned to ignore them. My conversation with Mr. M quickly faded into my memory.

Act 2

As luck would have it, I ran into Mr. M a year later. Without skipping a beat, he turns to me and says:

Mr. M: Well, did you invest in Constellation?

Me: No.

Mr. M: The stock has already doubled!

Me: Honestly, it’s just not for me. Buffett says don’t invest in tech stocks. The pace of change is too fast, and the future is hard to handicap.

Mr. M: Andrew, you should take another look. It’s not actually a tech company…

When I got back to my office, I entered the ticker CSU onto my screen. The first thing I notice is a company trading at 35x trailing earnings! What was Mr. M thinking? Value investors don’t pay those types of prices (sidenote: my thinking has evolved since then). I quickly moved on to research another business.

Act 3

On my first day at EdgePoint, Tye and Geoff asked me if there was a stock that I was interested in researching. After reflecting on it, I said there was this one company that’s been on my mind lately (the stock had now tripled since I first heard about it). They encouraged me to spend the next month studying the business.

When I’m researching a new company, the first thing I do is print off all the CEO letters (starting with the earliest one). Within five minutes of studying Constellation, I came across this section from the 2007 annual report:

I almost fell off my chair. A “tech” executive talking about flying economy and is concerned about spending shareholders’ money. My interest was piqued!

After several weeks of research, I sent a note to the CEO. I mentioned that we’re long-term, value investors and we’d like to meet with him to learn more about the business. Within a few hours I got a surprising response.

After sucking my thumb twice before, I ignored the CEO’s advice and we bought the stock. (This would be one of the rare occasions I disagreed with Mark Leonard.)

Club selection

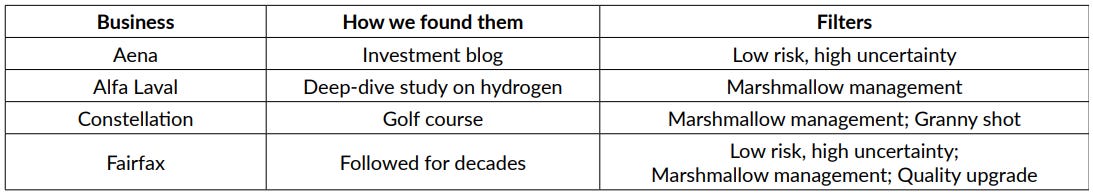

When investors ask how we get our ideas, our answer goes something like this – Good ideas can come from anywhere. In some cases, we’ve followed the business for decades. Other ideas come from attending a conference. We might read an article in the newspaper or find an idea on an investing blog. And the best idea I’ve ever had came on a golf course!

(I have played many rounds since and am still waiting for my next idea.)

This answer is probably unsatisfying to most prospective investors who are used to hearing about stock screens. Running quantitative stock screens can be an effective tool to filter the universe of thousands of companies into something more manageable. If you’re a “deep-value investor”, you might run a screen looking for low multiples of book value or free cash flow. A “quality investor” would run a screen looking at companies with high returns on capital and stable margins. Or a “growth investor” would search for companies with above-average revenue growth. You might be surprised to hear this, but I’ve never found an investment idea from a screen.

Why? We’re looking to buy growth for free. The only way to do this is by having a different view of a business than other investors. This often means finding companies whose future will be different (hopefully better!) than their past. Stock screens look backward and assume that the past is a good predictor of the future.

So, if we don’t run screens and our source for ideas is unpredictable, then how is our process repeatable?

Over the years, we’ve found that our successful investments often had one or more common traits. It took decades of investing (and making lots of mistakes) to identify these patterns, and they won't show up on any stock screen. If you were to look at our Portfolios, you will find all the ideas share a common set of patterns.

When I come across a new idea, the first thing I do is to run it through our list of filters. Is this a great business in a bad industry? Is it a non-obvious growth company? Does it have a "granny shot" culture? The more filters it hits, the more attractive the idea becomes. Essentially, we do use a screen, but instead of using it to find an idea, we use it to determine whether it’s worth investing in the business.

Let’s walk through a few of these filters (while there are many more, I want to be mindful of readers’ time). We’ll use both current and former Portfolio holdings to illustrate the concepts.

Filter #1: Low risk, high uncertainty

Investors often confuse risk with uncertainty. We see risk as the potential for permanent loss of capital, while uncertainty means not being sure of what happens next. Low risk and low uncertainty seem appealing, but one of the things we're certain about is that everyone knowing the future means that everything is priced properly. Mispriced companies are what allow us to buy growth and not pay for it.

Investors hate uncertainty and stocks get punished when they have uncertain outcomes. Great opportunities can emerge if you can find a business with low risk and high uncertainty.

Let’s use an example. In 1975, Bill Gates dropped out of Harvard to start Microsoft. At the time, his parents were concerned. Bill had worked extremely hard to get an Ivy League-education and was throwing it away to join a start-up with a high probability of failure. But Bill understood the difference between risk and uncertainty. While his future was highly uncertain, the actual risk was very low.

Portfolio example – Aena

When we invested in Aena in 2017i, it seemed like a risky investment. Aena owns all of the airports in Spain and the country was in a deep recession. Unemployment had spiked to 26% and domestic passenger traffic had fallen by 30%. Airports have a lot of fixed costs and Aena was only operating at 59% capacity. Even if people don’t travel, you still have to buy insurance, heat and cool the airport and pay your employees.

While the investment appeared scary, we saw a business with low risk and high uncertainty.

It was a question of when, not if, travel would recover. Aena’s business model was a lot less risky than other airport operators as they owned the real estate, had 46 different locations and had already invested in their infrastructure. The lack of visibility allowed us to buy a monopoly airport owner at an extraordinary price (at approximately 10x free cash flow).

Filter # 2: Marshmallow management

We love to find companies that are run by “marshmallow managers”. This doesn’t mean we think they’re soft, but that they’re willing to defer short-term gratification to increase long-term value. Sometimes this means spending years investing in a new product before you generate any revenues. Other times it could be building out the infrastructure to enter a new geography. Companies that ignore short-term profitability have an edge over those that are trying to please Wall Street.

In my Q4 2016 commentary, I explained the source of the name – a 1960s Stanford University experiment that shows that children often took immediate gratification (one marshmallow immediately) rather than waiting for a better payoff (waiting 10 minutes for two marshmallows). We still think that the market is full of people who have trouble delaying gratification, meaning that businesses that take time to grow can be undervalued by the market.

Portfolio example – Alfa Laval AB

At the beginning of the pandemic, many companies slashed costs. Nobody knew how long the pandemic would last and cost cutting seemed like the prudent thing to do.

Alfa Laval did the opposite. In the five years before the pandemic, Alfa Laval had invested heavily in their service, sales and R&D teams. Because of those significant investments, the company was winning. At the onset of the pandemic, management made the decision that nobody would lose their job. Their investments in people and R&D were the foundation for many great opportunities in energy storage, renewable diesel, biotech and the list goes on.

Alfa Laval’s CEO understood that the time to take market share is after downturns. Sure enough, orders were up 17% in 2021 over 2020 and they are entering 2022 with an order backlog that’s 27% larger than the previous year. Alfa Laval has distanced itself further from its competitor by not taking its eye off the longer-term prize.

Filter #3: “Granny shot” culture

Culture is one of the most underappreciated aspects of investing. Just because it’s hard to measure, doesn’t mean it doesn’t count (a lot).

One of the patterns we look for is what I would describe as a “granny shot” culture. In last year’s commentary, I talked about Wilt Chamberlain’s record-breaking streak. The one weakness in Wilt’s game was his inability to efficiently shoot free throws. The best solution would have been to use the granny shot (shooting the ball underhanded). Unfortunately, he wasn’t willing to be ridiculed for being different and he left many points (and records) on the table.

Portfolio example – Constellation Software Inc.

Let’s go back to the Constellation story. It might have sounded like luck. That’s because it was. What happens if I don’t golf that day? Or what if I don’t run into Mr. M again? Or if I joined a firm that wouldn’t invest in high-multiple stocks? Lucky.

But there’s also pattern recognition involved. The reason I picked Constellation (and not another company) was because of their granny shot culture – doing something highly unconventional and sticking with it.

Why was a software company studying Warren Buffett? Which technology companies focus on keeping costs down while they’re growing rapidly? How many CEOs would tell a potential investor not to look at their company?

Each of these questions individually didn’t strike me as a reason to invest in the business, but combined they told the story of an unusual corporate culture. Here are a few more examples of Constellation’s “granny shot” culture:

Instead of holding conference calls or providing guidance, they hold an annual meeting where investors can talk directly with management

They’re a serial acquirer but don’t focus on synergies

As they’ve gotten bigger, they continue to focus on doing small things really well. How many other $50 billion companiesii would be interested in a $1 or $2 million acquisition?

None of these things would happen at a company with a conventional culture that’s worried about looking different, but they’re key parts of what makes Constellation such a great business.

Filter #4: Quality upgrades

My favourite type of businesses are companies that are undergoing a significant change that hasn’t yet been recognized by the market. We call these quality upgrades. These are businesses that are going through a multi-year journey to improve the quality of the organization.

We have observed that investors are slow to recognize inflection points. People tend to form strong views about a business and assume that what happened in the past is a good predictor of the future. If a business has a lot of momentum, it will continue. If a business is prone to missteps, it will keep making them. This means that quality upgrades can remain undervalued for a very long time.

The beauty of investing in a quality upgrade is there are multiple sources of value creation. When the business improves, profitability follows. As the quality gets better, it gets reflected in a higher valuation. And there’s often a third leg of the stool where the better business now has more attractive re-investment opportunities.

What are the different types of quality upgrades? One category is when the industry or business model improves. For example, a business might go from being capital intensive to capital light. Brookfield spent many decades investing their own capital (capital intensive). Over the past decade, they have built out a successful asset management (capital light) franchise that generates significant profitability. Another one of our holdings, Onex, is following in Brookfield’s footsteps and is at an early stage of moving from a balance sheet investor to an asset manager.

Another common type of quality upgrade is when a great business isn’t living up to its true potential and a new leadership team is recruited to transform the business. These companies often have competitors that are generating significantly higher growth and profitability. The new team puts in place best practices to narrow the gap or even leapfrog their peers. Many of our largest investments are at various stages of their transformation. Shiseido, Aramark, Element, AutoCanada, Uni-Select to name a few.

When you’re looking for quality upgrades, there’s often a catalyst. An acquisition of two competitors leads to a more rational industry. New management comes in and changes the culture. The hardest ones to spot are where the industry or management hasn’t changed. In these rare instances, we’re betting on the existing management to learn lessons from the past.

Portfolio example – Fairfax Financial Holdings Ltd.

This brings me to Fairfax Financial, a business we hold across our Portfolios.iii If you ask any professional investor about Fairfax, they’ll tell you all the reasons not to own the business (the list is long). Fairfax’s stock price is the same as it was over 20 years ago. Many people have been burned thinking this time is different.

A few years ago, I had lunch with a Bay Street legend. Noticing that we owned Fairfax in our Portfolios, he asked why. I started walking him through our thesis about how the insurance business has improved. Before I could finish, he blurted out:

“You bought Fairfax for the insurance business? That’s like buying Playboy for the articles!”

What do we think others are missing? Fairfax has quietly been transforming into a durable growth company.

The property & casualty insurance industry is in one of the strongest pricing environments in a generation. Fairfax has more than doubled their premiums over the past five years (yes, it’s a growth stock!).

In June 2020, CEO Prem Watsa bought US$150 million of stock calling the company “ridiculously cheap”.vi What did the stock do? It subsequently went down in price!

Management has been shareholder-friendly taking aggressive actions to close the substantial discount to intrinsic value. They recently completed a US$1 billion share buyback. The market has started to take notice of all the improvements at Fairfax. However, at less than 1x book value, we continue to think Fairfax is trading significantly below what the business is worth.

As for the legendary investor, if you can avoid the distractions, sometimes the articles are the best part.

The 19th hole

Anyone familiar with EdgePoint knows what we look for in businesses – strong competitive positions, barriers to entry and long-term growth prospects run by competent management teams. But this isn’t enough. If you want to buy growth for free, you need to have an idea about a business that isn’t widely understood.

Over the years we’ve developed a set of unconventional patterns that can result in great businesses being mispriced. Investors avoid uncertainty – they don’t like to defer gratification, they prefer the conventional and would rather own companies that are already great instead of ones that are on a journey to get better.

Seeing them isn’t always easy, but that usually means other people miss them, too. By continually applying our investment approach, we believe we can keep buying businesses at prices below what they’re worth to help investors get to their Point B.

Thank you for your trust. We work hard every day to be worthy of it.

Wrap-up

If you’ve got any thoughts, questions, or feedback, please drop me a line - I would love to chat! You can find me on twitter at @kevg1412 or my email at kevin@12mv2.com.

If you're a fan of business or technology in general, please check out some of my other projects!

Speedwell Research — Comprehensive research on great public companies including Copart, Constellation Software, Floor & Decor, Meta, RH, interesting new frameworks like the Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3), and much more.

Cloud Valley — Easy to read, in-depth biographies that explore the defining moments, investments, and life decisions of investing, business, and tech legends like Dan Loeb, Bob Iger, Steve Jurvetson, and Cyan Banister.

DJY Research — Comprehensive research on publicly-traded Asian companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Nintendo, Sea Limited (FREE SAMPLE), Coupang (FREE SAMPLE), and more.

Compilations — “A national treasure — for every country.”

Memos — A selection of some of my favorite investor memos.

Bookshelves — Your favorite investors’/operators’ favorite books.

Wonderfully written Andrew!