Letter #217: Mike Cassidy (2010)

Benchmark EIR and 5x Exited Founder | Speed as THE Primary Business Strategy

Hi there! Welcome to A Letter a Day. If you want to know more about this newsletter, see "The Archive.” At a high level, you can expect to receive a memo/essay or speech/presentation transcript from an investor, founder, or entrepreneur (IFO) each edition. More here. If you find yourself interested in any of these IFOs and wanting to learn more, shoot me a DM or email and I’m happy to point you to more or similar resources.

If you like this piece, please consider tapping the ❤️ above or subscribing below! It helps me understand which types of letters you like best and helps me choose which ones to share in the future. Thank you!

Today’s letter is the transcript and slides of Mike Cassidy’s 2010 talk Speed As THE Primary Business Strategy. In this talk, Mike shares why speed brings great advantages, compares the typical start-up timeline with the lightning-speed start-up timeline, and discusses four examples of lightning-speed speed start-ups. He then gives a quick overview of the start-up journey, calling out the parts that can be sped up, then digging into each one individually: 1) fundraising, 2) opening an office, 3) hiring, 4) getting new employees started, 5) product development, 6) business development, 7) marketing/PR, and 8) changing direction. He ends by taking a few questions from the audience.

Mike Cassidy is currently simultaneously the CEO of D-Orbit USA and the CEO of Vulcan Fusion. Prior to D-Orbit and Vulcan, Mike was the Cofounder and CEO of five exited startups in five different industries: Apollo Fusion (acquired by Astra for $145mn), Ruba (acquired by Google), Xfire (acquired by MTV for $110mn), Direct Hit (acquired by Ask Jeeves for $532.5mn), and Stylus Innovation (acquired by Artisoft for $13mn). After Ruba’s acquisition by Google, he served as a VP and spent 5 years as the Project Leader of GoogleX’s Project Loon. He was also an Entrepreneur-in-residence at Benchmark Capital and studied jazz piano at Berklee College of Music.

I hope you enjoy this presentation as much as I did!

[Transcript and any errors are mine.]

Related Resources

Benchmark

Investors

Letters

Compilations

Bill Gurley Compilation (652 pages)

Mitch Lasky Compilation (474 pages)

Sarah Tavel Compilation (300 pages)

EIRs

Musicians

Start-up Tactics

Slides + Transcript

The faster you can roll out a product makes it really hard for, obviously, for the competitors to keep up with you.

One of the examples I give is my third company, XFire. And that company, we were rolling out -- it was an instant messenger for PC video gamers -- and we were rolling out a new release of the product every two weeks. And there were some major competitors in the instant messaging space, including AOL. And AOL identified us as a competitor, and they started to design a reaction to our product. But larger companies -- it was approximately 12 months -- their process of identifying, defining the product they wanted to use to compete against us. And by that time, we already had 24 releases. And so the plan for counteracting us was not going to work. So one is against competitors.

The second is, first, team morale. I'm a huge believer in the importance of team morale. Whenever I meet with my one on ones, with people in my company, the first thing I ask them is, Are you happy? Because I think that happy people are literally 10x more productive than people who aren't happy. And if your company is moving along very quickly, it tends to make people happy and excited about the pace and the prospect of the company.

Third, from a PR perspective, it's great when you can meet with someone from the press and give statistics -- and we have 2mn users, whatever, and they can say, Well, I just met with you two months ago, and you only had 1mn users. That kind of momentum is great for press. Press loves to see the fast pace. And the last reason, obviously, drives higher valuations. Higher valuations when you raise money, and higher valuations when you're selling the company.

And also, you can give to the companies -- I don't know how many people read this article; it talked about local companies -- but I believe in selling the company, for maximizing value, at the point when the company is still growing exponentially. When you're growing exponentially, if you can imagine this curve, it just is very exciting by what the prospects are. Once your company starts growing linearly, it's very easy for acquirers or investors to say, Well, I can project that out exactly what's going to be in two years from now.

So I'm going to try to contrast the typical startup timeline with this rapid startup. And maybe some of these numbers are even too slow -- typical -- maybe this is not even typical anymore. But just for an example, take the case of a company which takes, say, three months to sort of kick around some ideas. Maybe it takes three months to raise money, maybe it takes a couple months to hire the core team and open an office, and maybe it takes 12 months to really build a good product. And then there's a period of 3-6 months of starting to get market awareness of... So the whole process is 23-27 months.

All four of my companies have been quite different. Exploring ideas is a two week process, and we could talk more about -- I honestly believe you should not spend more than that time, because you'll just find reasons not to do it. When I was a -- the longer you look at it, there'll be more reasons -- well, other company's doing it, things like that. Raising money -- and I have up here one day.

Sometimes when I give this speech, people throw things at me. This is an aspirational speech. I have been very fortunate. I've raised eight rounds of venture money, and seven out of the eight rounds, I did get a signed term sheet on the day I pitched.

And I'll talk a little bit about how you too can do this; how you can raise money the same day you pitched.

Opening -- hiring the core team and opening the office.

We'll talk about -- execution is where it's at. And we'll talk about how we did some of those. And finally, building the products. All of my companies -- the successful product was built in three months. And that is intentional, in the sense that it's not: you get together the engineering team and say, Well, how long will it take. You say, Okay, in three months, what can we build? And we'll talk about why we do it that way. And this results in a company launching three and a half months or so after you’ve started.

Okay, so many people are not that familiar with some of the companies that I've done, so I just want to quickly talk to you about them.

The first one was called Stylus Innovation. But the initial name of this company was Dial-a-fish. Literally, Dial-a-fish. It was going to change the way everyone ordered groceries in the United States. It turned into a computer collecting software.

When we started, there were -- 95% of the market was owned by DOS-based tools. And then the typical competitor had 300 customers. We were the first Windows-based tool, and we shipped 3,000 copies of our product in the first year. It was a very simple company. This one -- you can see -- we sold it for $13mn, which is tiny for Silicon Valley standards. The nice thing about that one is: there was only $1,500 in investment in that company. I put in $500, each of my two partners put in $500. So it's got a 10,000x ROI, I guess, on that one.

And the thing about this company is, as you'll see from -- three out of my four companies, the original idea was a disaster. It had to change direction.

And this one -- as we were building this Dial-a-fish product, it was -- I hate to admit my age, but it was before the internet. And you'd have in your house, you'd have, as you were throwing away your box of cereal, you'd take a pen-sized wand and you'd scan it over the barcode on the product, and you would go over to the telephone, convert the barcode into touchtones, and those touchtones would be understood by a computer, which would then know the product you're throwing away and have it ready the next time you go to the store, packaged up -- this is pre WebVan, too.

Well it turns out, in the process of building that product, we realized that all of the tools out there for building interactive force response applications -- the applications which link telephones and touchtones to computers, were terrible, because it's DOS-based tools, and we built the first Windows one.

The second company was Direct Hit. Direct Hit was an internet search engine based on tracking what sites people clicked on and how much time they spent there. And this was launched in 1998.

At the time we launched, we were on the cover of a magazine called Industry Standard -- with Google. And it was a -- if someone spent five seconds at the site, we penalized it. If someone spent five minutes at a site, we rewarded it. But anyway, we provided search results for AOL, Microsoft, Lycos. We got this AOL deal within five months of the company starting. I'll talk about that company a little bit more. And that was the one -- 500 days after we launched for $500mn. So that was a fair return also.

The third one, Xfire, was this instant messenger for PC video gamers. It was -- a beautiful thing about this product was it was a viral spreading product. You could look at your instant messenger and you could see your friends showing up in your IM client, and you could see what online game they were playing. These were shooter games -- Doom, Quake, and things like that. And you could just click on your friend's name, and it would launch you into the same game your friend would play. Well, the great thing about this product was it was completely useless to you unless your friends were also using it, which means, anyone who touched the product had to go get their friends to use it. And in fact, it was extremely viral. The average user got five of his friends in the first three weeks to start using the product. This grew to 3mn users in two years. We sold it to MTV for $100mn. And it was a new segment.

And also you'll see from the companies I've done: one was computer telephony, one was internet search, one was instant message for PC video gamers, another one was a recommendation engine. All different spaces. I love going to different spaces, and I also encourage people -- they say, Oh, I'm not an expert in that space. I think that's great. Sometimes people new to the space are not sort of entrenched in the ideas people who have been there too long say you can never do that.

And also it's fun for me, because in the beginning, nobody calls me back -- even my third and fourth company. In a new space, I have no reputation in that space, so nobody calls you back. It's very frustrating at the beginning, but over time, then, like 9-12 months into it...

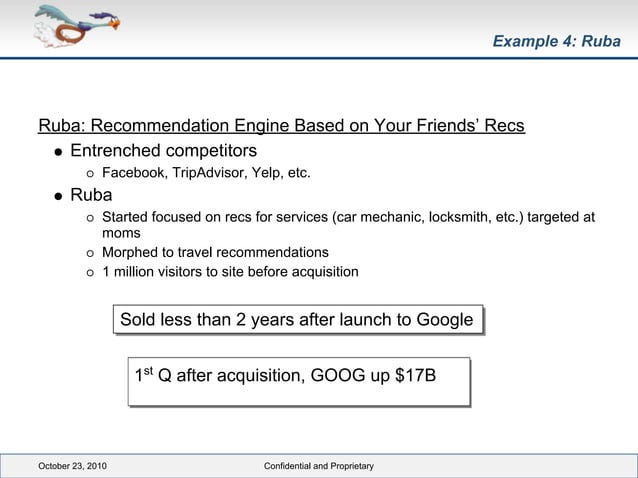

Let's see. The fourth company, Ruba, was based on recommendations, based on your friends' thing. And that was, again, had to morph from -- the first idea really didn't catch on. We sort of turned it into a travel site, and that's when we sold to Google.

Okay, so how do you speed up all parts of a startup, whether it's -- and these are the things --raising money, opening your office, hiring people, what you do for new employees, getting them started. How do you speed up the product development process, business development, marketing, and how do you speed up the process of changing direction? And we're gonna talk through each one of those.

So fundraising.

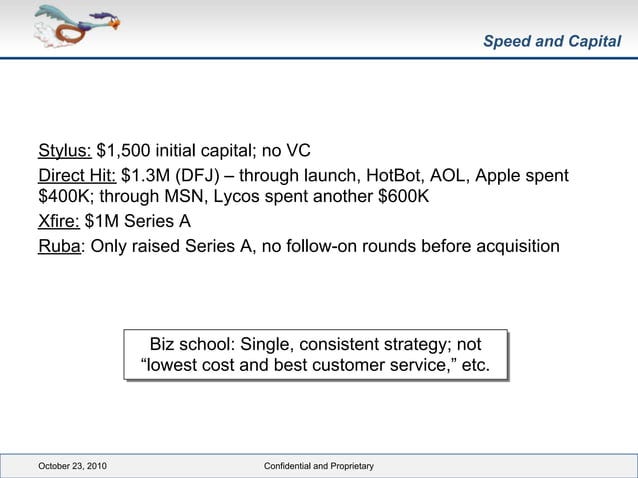

Not a lot of money has gone into the companies I've done, which I think is also very encouraging for, hopefully, people in this room. It's not like you have to go get $10mn as your first step.

Again, Stylus was the one -- was $1,500. Direct Hit was -- the Series A was only a $1.3mn investment. And that's the one -- I pitched DFJ at 8:15 in the morning, and they gave me -- they found me, they tracked me down and gave me a term sheet at 4:30 that afternoon. And we didn't even invest -- we didn't even spend that much money. We got HotBot as a customer, and AOL, and Apple -- and we'd only spent $400,000 at that point. And then, even then, we got Microsoft and Lycos as customers of our search engine -- we'd only spent another $600,000. Xfire was only a $1mn Series A round.

And I talk here at the bottom about this business school philosophy of having a single, consistent strategy. So if your strategy is speed, I think it also applies to fundraising. Basically, it's faster to raise lower money -- it's faster to raise less money than to raise the bigger rounds. And also, raising lower money forces you to be faster. You don't have that much money, you're going to run out of money soon, so you have to move quickly.

And so how do you raise this venture capital money quickly -- the same day close?

So here's some things that I do.

First of all -- some of this is obvious, but the examples: raise when the conditions are totally in your favor. And to me, that doesn't necessarily mean just following a key event, but sometimes right before a key event. For example, I talk in here about Direct Hit's Series B. When we were about to close the AOL deal, where AOL is going to start using our search engine as part of the results for them, I was approaching venture capitalists and saying, I guarantee you my valuation is going to go up next week when I close the AOL deal, soo if you want to come, now is the time to do it. And we did the same thing when we're raising money for Microsoft and Lycos -- for the Microsoft and Lycos deal. deal. We knew those deals were going to close, and we raised money just before that.

Second thing is getting all the decision makers in the room. When I talk to investors, I tell them, This is moving very quickly, and so, very excited you're willing to meet with us, but I need to have all your decision makers in the room for that meeting. And some people will say, Goo jump in the lake. But some of them will say, Wow, this person really must have something if they have a temerity to say, Get all the decision makers in the room. And sure enough, you're gonna avoid the delays you get sometimes with -- meet with first this associate, and then come back and meet with one partner, then come back and meet with two partners, and then -- just don't do that. My advice is to try to get all the decision makers there.

Third thing is obvious -- synchronize your timing of your offers. And I will be very upfront with them. I'm saying, Yes, I'm meeting with one firm at 10 o'clock, one at one o'clock, one at three o'clock. And I said I'm expecting a term sheet at five o'clock today. And it's, again, it's quite a bold approach. But they sort of get this feeling that something is coming.

And a more concrete thing you can do is: I love to bring what I call if-then contracts to my VC meetings. And an if-then contract -- I will get a customer, basically, a customer. With Direct Hit, we got Alta Vista and Infoseek to both basically write me a letter saying, Yes, Mike, if you design a search engine that has 50 millisecond response time and 80% of our users think your search results are better than our current search results, Sure, we'll use your results and we'll pay you $1 per 1000 results. These companies are not too worried about signing a letter like that. It's probably not even legally binding. They don't really think you're going to get to achieve what you just said you'd do. But when you walk into the venture capitalist with that letter in hand, you've basically eliminated 50% of things they worry about. They worry about whether you'll be able to sell, will you have customers? Now you'll say, Yes, I got customers.

The other thing I worry about is, technically, can you build it? So in all the cases I've done, I've gotten together before going to the venture capitalist, and like with Direct Hit, we had this really excellent database designer, and we did a Gantt chart, what the development of the product's going to take? It's going to take 12 weeks. It's going to have these three people working on it. These are the tasks. The VCs have no idea whether this Gantt chart is right or not, but they say, Well, this person, they've thought it through, maybe I feel good about the technical risk I'm taking.

And these are things you can do before you go and meet with a venture capitalist. And again, it's going to show that you're thinking is: I focused on a customer, and I focused on how to build it. And I think it goes along with getting those.

And the next thing: opening an office. I'm just very proud about the nuts and bolts, the execution of things.

So we raised this money, this is the one -- this is the Direct Hit one, where we've got the term sheet on the same day of that morning. Before I even got on the plane to fly back, I called the developers in Boston and said -- because this was actually based in Boston -- quit your job, we're gonna start. And the next day, I was negotiating a lease on office space and ordering the computers. And you can see all the steps here -- the the network software, the phone system, the alarm system, incorporating, setting the bank account. Just got to be really good at executing all these things so that 11 days later, you can open an office with everything there, and just your speed is -- you're hitting everything with speed.

I apply the same thing to hiring.

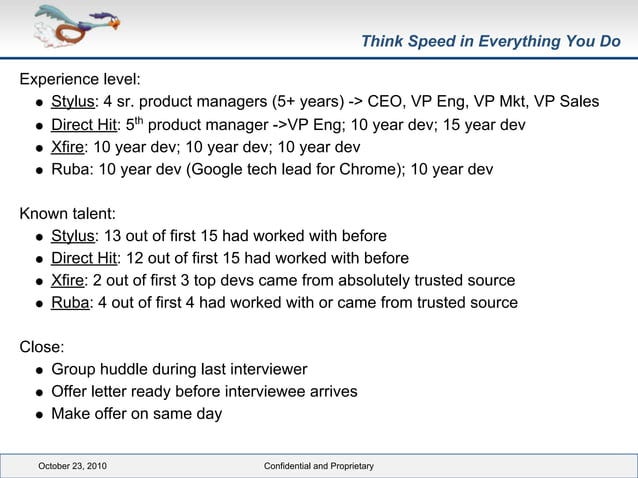

Now, first of all, this is a little look at the type of people I've hired in my companies. And you'll see that a lot of them have a lot of experience. Because I love the energy and enthusiasm of people right out of school, but in my experience, it's been -- a developer who's got five or seven years of development can be so much faster.

And a lot of these companies were built with just three developers. Xfire and Direct Hit were built -- the core product was built with three developers. And I talk about 20x developers or 30x developers -- to me, that means someone, literally, who can -- one developer can do the work of, in one day, can do what it'll take another developer 20 days to do. And you can find those people.

So anyway, look for people with [experienced backgrounds]. And all these people, often, they are people I've worked with before. You can see, Stylus, 13 out of the 15 I've worked with before; Direct Hit, 12 out of 15 I worked with before.

And how do we hire people quickly?

One of the things I like to do is have all the interviews done on the same day. So the people come in, and they might have five interviews or six interviews starting at noon or something like that. But as the interviews are going along, if I find someone who's -- people like, Yeah, this person is good, I will do a real time reference check at three o'clock in the afternoon or something. And all my friends are used to this now. They're like, Oh, this is another reference check -- you need an answer within a half an hour. Yes it is.

But it builds this momentum. And you never take the references people give you. You always find where they've been and find someone you know through your network who's been at that company who can speak about them. So do all the interviews on the same day. At the end of the day, before they walk out, you hand them an offer letter and you say, We're really excited. We're giving you an offer. Are you ready to join? And they say, Woah, wow, I didn't expect this. I need to think about this. And you say, Great, I don't want to rush you. Can you call me at nine o'clock tomorrow morning and let me know? But seriously, that's the kind of intensity that -- you can avoid getting in these bidding bidding wars with someone else trying to get them. You avoid getting them cold feet -- if they think about it for too long, they don't want to join. And again, it sets the pace. So when they come to your company, they're expecting this pace.

Same thing with getting new employees started.

For me, it's a cardinal sin to have someone start, and they're all excited, the first day, and you're like, Ah, the computer's not quite set up yet, your email account's not quite set up yet. We forgot forgot to order the source control license, so read these manuals -- or something like that. That's a sin.

Before they come, you should have them doing their -- whatever it is, W2 paperwork and all that stuff -- don't do that the first day they come.

And when they come, you should have every single piece of hardware and software ready for them to start. And you should have the task list set up: here's the task, here's the project.

First of all, it's very efficient. Second of all, talk about setting the tone, setting the pace, the intensity. When someone walks into an environment like that, they're like, Alright, this is for real.

Okay. Product Development.

We'll make this an interactive session.

And this is actually a tough choice, so you have to decide.

If you have a choice between incremental development, where you're just going to build one feature and then add another module maybe a little bit later, and then add another module -- keep adding features as you go, and listen to the market and add features.

Or your choice two is, No, no, no, you got to do a good job -- you have to spec carefully. You have to do good research, because you don't just want to design a vacuum. And youyou want to make sure you get the product a very good product the first time, because you're only going to get one impression. Once someone tries your product, if they don't like it, they're not going to come back and try it again.

So how many think Option A is the way to go for a speedy deal?

How many people think Option B?

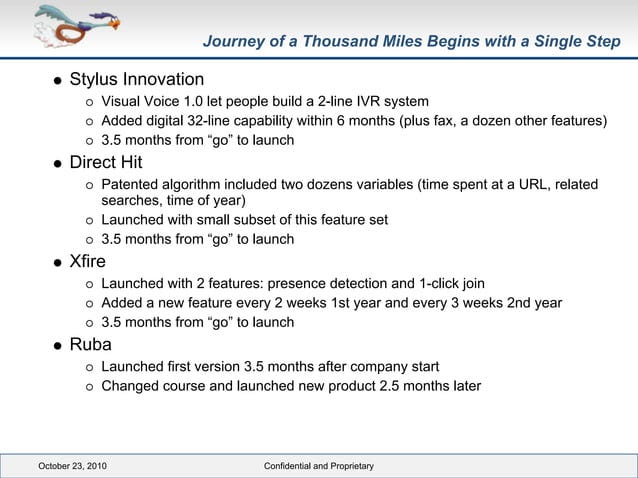

OK, so I've always gone with Option A. And, it's tricky, because they're both sort of compelling solutions. But all of the products I've launched, the very first -- Version 1.0 of the product has been extremely simple.

This is the first computer telephony product. Eventually, it was a digital system and handled 64 simultaneous lines, it had fax, and all this voice -- [auto-intent] and all this stuff.

The very first version, it handled two lines, analog lines on the telephone. That's all it did. Same thing with Direct Hit, the search engine. The first version we launched, all it did was count clicks. This site has been clicked on 17 times, this one's been clicked on 46 times. It didn't include any of this timing, three seconds, five seconds. It didn't include US Open tennis versus golf by time of the year. It was a very simple version. Then we just add features as we go along. It simplifies your development effort, it simplifies your marketing effort, and it just is a much -- I think it's a much faster way of…

Okay, yes. So here are some of these examples I just talked through about the different features.

Okay, business development.

How can you close business development deals quickly?

So I have this saying -- I have all these little silly sayings in my companies, and people always -- one of my sayings is, The chance of anything good happening is never greater than 50%, which really annoys people when I say that.

Another thing I always say is, What can go wrong? And when developers come into my office and say, Yes, it's going to work perfectly, I would just say, What can go wrong?

So one of the ones I say is, The probability of any deal ever closing declines by 10% for every day it does not close. And I really believe this.

So it changes your behavior. If you're starting to deal with someone who you think it's going to be a 2, 3, 4 week, 5 week, 6 week cycle, I will just say to them, You know what? If we don't close this deal today or tomorrow, I just don't think it's going to close. And I'll be much more bolder.

And at first I was really scared. I was like, Oof, if I push them too hard and I don't get the deal, then maybe I'm making a mistake. But then I realized over time that, at least in my experience, everyone is so busy, and they only have maybe two or three things that are at the top of list they can get done in any given day. If you're not on that list of things that are going to get done that day, you're not going to get done. And it's going to be the same next day. You're going to be number seven on that list the next day, and number seven on the list the next day.

So I push -- you might not be surprised --but but I push to get the deals closed. And all the deals -- let's say, take Direct Hit -- the deal with Microsoft was done in 10 days. This is a deal where we basically provided search results at the top of Microsoft search result list. That was done in 10 days. The AOL deal was also done in about two weeks. And the ones that took longer, the Infoseek deal, the Alta Vista deal, those stretched into months and months, and they actually never closed.

Also, the limited supply thing -- and this is a standard thing, right? Limited supply. Oh, well, we've already sold the sponsorships for July, August, and October. September is still available, but there's someone else who wants it. I mean, that's a stupid trick; you've all heard it a million times. But that stuff works. People, they feel a deadline, it feels of limited supply. And maps, if there are certain regions that are all being taken up, that just drives people crazy. Like they're gonna lose out, they're gonna miss.

The biggest thing you can get to get people to get to move is their fear of their competitors. You talk about what their competitors are doing. And I'm very open. I tell people, Yeah, of course I'm talking to your competitors. And I don't reveal any confidences, but I say, Well, I just want you to know, I thought I'd warn you, and if you see the announcement of us partnering with one of your competitors, don't say I didn't warn you. And that drives them crazy.

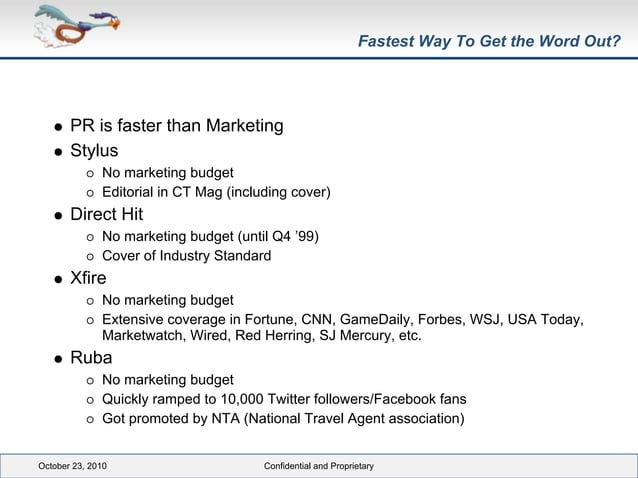

Marketing.

So another way of moving fast is this tension between PR and marketing -- I'm going to really end up annoying a lot of people who are big fans of marketing. But PR has worked much faster for me than marketing. Marketing has delays delays in it. There's a delay in the creation of a marketing material, there's a delay in both coming up with what the ideas are and then actually production of it.

And if I just look back at my companies -- Stylus had no marketing budget at all. We were -- our strategy was to get editorial in Computer Telephony Magazine. We were on the cover of Computer Telephony Magazine I think three times in the first year we were at. Direct Hit, we had no marketing budget. We were on the cover of Industry Standard.

And a lot of the times, the way you get these -- I used to have this sort of fantasy. I wished that Star Wars was real. The force in Star Wars. When they use the Force, and they say, I wish I could use the force and make that person sign this purchase order or whatever -- make this investor give me a million dollars -- using the force. But then I realized that actually it does -- it's true. You can do stuff with the force, if you can become a persuasive -- the charisma -- or whatever.

And I think that if you can get -- you can do that with press too. Press loves to deal with the actual entrepreneur. Because all day long they're dealing with PR people, and that's their job. Their job is to go and pitch the companies. But it's much harder for the reporter to believe when the PR person says, Oh, this is the greatest product I've ever seen, than the real entrepreneur. So I've always tried doing it directly myself.

Okay, changing direction.

So as I mentioned before, which, again, I hope is encouraging to people, because maybe some people are working on things now and maybe it's not quite working. Well, been there. Three out of my four, the product did not work.

Dial-a-fish we talked about. And once we -- I think the key is, once you decide it's not working, you have to be very decisive when you change direction. I think a lot of companies -- first of all, a lot of companies -- it's kind of sad to watch. They just death spiral in. It's not working and it's not working and it's not working, and they just crater. And they don't just change.

And other ones, they tentatively change. They say, Yeah, we've been at this for a year, and we have two customers. I'm not sure it's working, but -- so let's take 15% of the company, and we're going to work on this new idea as an experiment.

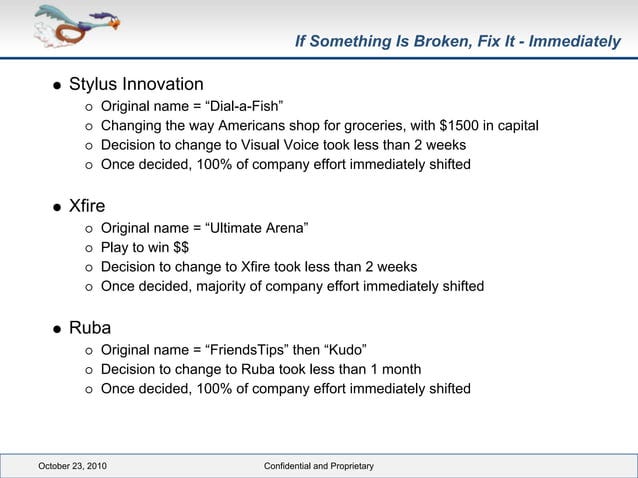

I think that's wrong. I think once you know it's not working, you've got to move the entire company immediately. You can see here some of these. The decision to change to Visual Voice took less than two weeks, and we moved the whole company over to Visual Voice.

With Xfire, when we switched -- the original -- Xfire didn't start as an instant messenger for PC video games. It started as Ultimate Arena, which was a place that people were going to come online to play these tournaments. They were going to put $1 in, and they were going to win money against the other people online. Once we decided to change direction, it took two weeks to change. And we switched the majority of the company over right away.

Same thing with Ruba, my fourth company. Look at how many names we went through -- FriendsTips and then Kudo and then Ruba. When we tried to change, we moved 100% of the company over.

Alright, so this is just the last aspirational one. And then get I’ll get into questions, because I've done these talks a few times, and people mostly enjoy the Q&A.

So anyway, this was Direct Hit, where we -- and some people who are into finance will love the multiples.

So we raised Series A at $1.3mn on $2.6mn pre. And that's the one where we opened our doors, 11 days later. We signed a deal with HotBot, which was like the fourth biggest search engine, a month after we opened our doors. So there was no way the product was done, but we got them to agree, Yes, okay -- with a real, signed contract -- Yes, we'll do this, we'll pay this much. And then two months later, the product was done, and we launched with them. Once we got HotBot as a customer, we were able to get AOL and Apple. And right as we're closing the AOL deal, that's when we did our Series B, which was $2mn on $23mn pre.

And then we got -- our link had gone from a link at the top of search result list to becoming the default results on HotBot. And then we got the Lycos and Microsoft deal. And as we're closing those deals, again, we used this time to raise. We raised $26mn at $100mn pre.

And then we launched this destination website. And this was -- this is the one that sold for $500mn.

So I'd love to take questions.

Q&A

Mike Cassidy: Are there questions? Go ahead.

Audience Member: On fundraising -- first of all, if your valuation is going up next week because you have those deals closing, why don't you wait and get a better deal from the VCs? Secondly, with development cycles that are so short, and so little money raised, why even bother raising the money?

Mike Cassidy: So why do I leave money on the table? I leave money on the table all the time because I don't believe in winning a negotiation. And I have this -- this is one of my sayings: I want anyone who's ever invested in me, anyone who's ever worked at one of my companies, any business development deal I've ever done, to want do another deal with me. So I always leave money on the table. Also, I think that -- I'll give up money for speed anytime. So, if someone is willing to give me, say, $1.3mn at 2.6mn pre today, I'll take that over maybe next week getting $2mn at $4mn pre or $5mn. Because I have this huge discount rate on the value of time. Like, enormous discount rate. And so to me, it's worth the time. And the second question was, Why raise money at all? So, I've had very good relationships with the investors I've had. And so it's not just the money. I mean, I didn't even need to really raise money for my second, third, and fourth companies. I could have just self-funded out of the money I made before. But the investors I had did a couple things for me. One is, they really would challenge me. And during monthly board meetings, they'd say, Well, why are you doing that way? This person over here does it this way. And even the original idea, they'd say, Well, make sure you want to do that. The second thing is, I'm -- like many people in this room probably -- a very big believer in the power of your network and your connections. And the introductions made for me by the investors I've had have been invaluable. I mean, DFJ introduced me to the AOL deal that got me that one. And Benchmark, I mean, unbelievable in terms of, You want to talk to the CEO of Verizon? Sure, tomorrow. Other questions?

Audience Member: You're optimizing your situation -- your situation and your investors’ situation -- but after a while, the companies buying your company -- how do they do, in general? And are they then poisoning the opportunity the next time around?

Mike Cassidy: No, no. In fact -- yeah, well, put it this way --

Audience Member: Because I've gone in behind companies that were struggling...

Mike Cassidy: Sure. I'm well aware of the problem. So one data point is: the first quarter after Google bought us, at the end that quarter, their market cap went up $17bn -- which I take full responsibility for. The second company -- Stylus. When Artisoft bought Stylus, they basically -- eventually completely closed out all their other product lines, and the only product they sold was ours. And so I think it was a great validation that we weren't just junk. Direct Hit was bought by Ask Jeeves, and that's a tricky one. It was kind of... kind of tricky timing because that happened right as the bubble was bursting in the spring of 2000. I think most people agree though, the technology we brought was very valuable to Ask Jeeves. I think the jury is kind of out on whether -- how successful that one has been. Xfire. When MTV bought us, we had 3mn users. About two years after that, we had 15mn users. So I think from a user growth perspective, it was pretty good. But -- go ahead.

Audience Member: If I was buying one of your companies, I would want you.

Mike Cassidy: Yeah, well --

Audience Member: I would want to keep you. Because you're the creative genius. And many companies struggle when that creative genius leaves.

Mike Cassidy: Well, Google is doing a really good job at treating me really well, so far. So, we'll see. Other questions?

Audience Member: The question is, Did you use bankers when you sold your companies? And in general, was it a proactive sale from your part, or did they solicit you and you just jumped?

Mike Cassidy: Right. Great question. I'm not -- in general, I don't believe you can sell your company. I think that companies buy companies, but it's almost impossible to knock on a door and say, Hey, buy me, buy me, buy me. Because the fact you're knocking on the door saying, Buy me -- it's kind of a big red flag saying there must be something wrong. Now, you can introduce yourself to companies by working on strategic partnerships with them, and then let them come to the conclusion they want to buy you, but no, I never called a company and said, Buy me.

If you got this far and you liked this piece, please consider tapping the ❤️ above or sharing this letter! It helps me understand which types of letters you like best and helps me choose which ones to share in the future. Thank you!

Wrap-up

If you’ve got any thoughts, questions, or feedback, please drop me a line - I would love to chat! You can find me on twitter at @kevg1412 or my email at kevin@12mv2.com.

If you're a fan of business or technology in general, please check out some of my other projects!

Speedwell Research — Comprehensive research on great public companies including Constellation Software, Floor & Decor, Meta (Facebook) and interesting new frameworks like the Consumer’s Hierarchy of Preferences.

Cloud Valley — Beautifully written, in-depth biographies that explore the defining moments, investments, and life decisions of investing, business, and tech legends like Dan Loeb, Bob Iger, Steve Jurvetson, and Cyan Banister.

DJY Research — Comprehensive research on publicly-traded Asian companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Nintendo, Sea Limited (FREE SAMPLE), Coupang (FREE SAMPLE), and more.

Compilations — “An international treasure”.

Memos — A selection of some of my favorite investor memos.

Bookshelves — Collection of recommended booklists.